Friday, 30 January 2026

Aus Open: Rybakina brushes past Pegula to set up final showdown with Sabalenka

Friday, 23 January 2026

Human heart regrows muscle cells after heart attack: Study

Friday, 9 January 2026

Millions of hectares are still being cut down every year. How can we protect global forests?

David Clode/Unsplash, CC BY

Kate Dooley, The University of Melbourne

David Clode/Unsplash, CC BY

Kate Dooley, The University of Melbourne

Ahead of the United Nations climate summit in Belém last month, Brazil’s President Lula da Silva urged world leaders to agree to roadmaps away from fossil fuels and deforestation and pledge the resources to meet these goals.

After failing to secure consensus, COP president Andre Corrêa do Lago announced these roadmaps as a voluntary initiative. Brazil will report back on progress at next year’s UN climate summit, COP31, when it hands the presidency to Turkey and Australia chairs the negotiations.

Why now?

These goals originate in the outcomes of the first global stocktake of the world’s progress towards the Paris Agreement goals, undertaken in 2023.

At the COP28 talks in Dubai in that year, there was an agreement to transition away from fossil fuels and to halt and reverse deforestation and forest degradation by 2030.

Yet achieving these goals relies on a “just transition”, where no country is left behind in the transition to a low-carbon future, including a “core package” of public finance to address climate adaptation, and loss and damage. The Belém outcome fell short.

Forests need urgent protection

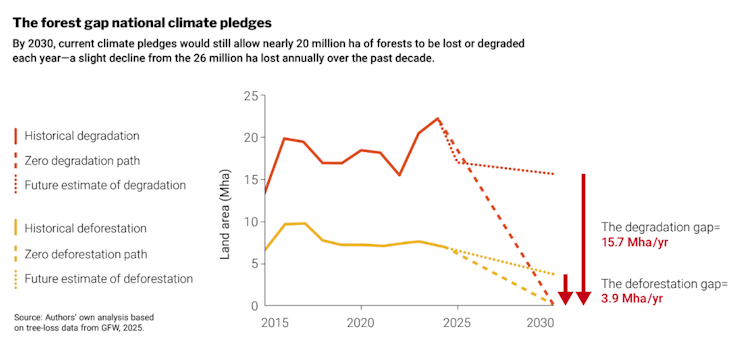

Forest loss and degradation is continuing, at an average rate of 25 million hectares a year over the last decade, according to the Global Forest Watch. This is 63% higher than the rate needed to meet existing targets to halt and reverse forest loss by 2030. Yet the climate pledges submitted for the Belém COP remain far off track from this goal.

In the 2025 Land Gap Report, my colleagues and I calculated the scale of this “forest gap” – the gap between 2030 targets and the plans countries are putting forward in their climate pledges.

We show the pledges submitted up until this year’s climate summit would cut deforestation by less than 50% by 2030, meaning forests spanning almost 4 million hectares would still be cut down. The pledges would lead to forest degradation – where the ecological integrity of a forest area is diminished – of almost 16 million hectares. This is only a 10% reduction on current rates.

Together, this equates to an anticipated “forest gap” of around 20 million hectares expected to be lost or degraded each year by 2030. That’s about twice the size of South Korea.

While this underscores the inadequacy of commitments, the analysis is based on pledges submitted up to the start of November 2025, at which point only 40% of countries had submitted an updated plan. Major pledges submitted during COP31, such as from the European Union and China, don’t change this analysis.

This graph shows that deforestation will only slightly decline to 2030. The Land Gap Report, author supplied., CC BY-ND

This graph shows that deforestation will only slightly decline to 2030. The Land Gap Report, author supplied., CC BY-NDForest wins in Belém

A new fund for forest conservation called the Tropical Forests Forever Facility was launched in Brazil, attracting $US6.7 billion in pledges ($A9.9 billion).

The forest fund focuses on tropical deforestation, the leading cause of emissions from forest loss. But it has a key weakness: the limited monitoring of forest degradation, which could allow countries to receive payments while still logging primary forests.

The fund will establish a science committee and plans to revise monitoring indicators over the next three years, creating an opportunity to strengthen its ability to protect tropical forests.

The COP30 leaders’ summit also saw the launch of a historic pledge of $US1.8 billion ($A2.7 billion) to support conservation and recognition of 160 million hectares of Indigenous Peoples’ and local communities’ territories in tropical forest countries.

But global action on forests needs to extend beyond the tropics. Across both deforestation and forest degradation, countries in the global north are responsible for over half of global tree cover loss over the past decade.

Beyond tropical forests

A global accountability framework on forests is needed to increase ambition on climate action, including in countries and regions with extensive forests outside of the tropics, such as Australia, Canada and Europe.

In these regions, industrial logging is a major driver of tree-cover loss but receives far less political attention than tropical deforestation. Wide gaps in reporting – between deforestation and degradation – mean logging-related degradation often goes unreported.

In a recent report, only 59 countries said they monitor forest degradation. Of these, almost three-quarters are tropical forest countries.

The IUCN World Conservation Congress which convened in Abu Dhabi this year prior to the climate talks, passed a motion on delivering equitable accountability and means of implementation for international forest protection goals. This arose from a recognised need to promote greater equity between forest protection standards across countries.

All of this points to an urgent need to tackle accountability in global forest governance. The forest roadmap to be developed for COP31 in Turkey could help drive stronger alignment and transparency across UN processes – from the UN Forum on Forests’ 2017–2030 plan to the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework’s 2030 target to halt and reverse biodiversity loss.

Australia could lead on forests

Australia could help shape global forest ambition in the year ahead. It is currently the only country whose emissions pledge promises to halt and reverse deforestation and degradation by 2030 – a clear signal that developed countries must lead.

As President of Negotiations at COP31, Australia can also work to bring Brazil’s fossil-fuel and forest roadmaps into formal negotiations. But this depends on two things: credible leadership from developed countries and long-overdue climate finance. As a deforestation hotspot with ongoing native forest logging, Australia has considerable work to do to meet this responsibility.![]()

Kate Dooley, Senior Research Fellow, School of Geography, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Friday, 21 November 2025

57% of young Australians say their education prepared them for the future. Others are not so sure

Lucas Walsh, Monash University

When we talk about whether the education system is working we often look at results and obvious outcomes. What marks do students get? Are they working and studying after school? Perhaps we look at whether core subjects like maths, English and science are being taught the “right” way.

But we rarely ask young people themselves about their experiences. In our new survey launched on Tuesday, we spoke to young Australians between 18 and 24 about school and university. They told us they value their education, but many felt it does not equip them with the skills, experiences and support they need for future life.

Our research

In the Australian Youth Barometer, we survey young Australians each year. In the latest report, we surveyed a nationally representative group of 527 young people, aged 18 to 24. We also did interviews with 30 young people.

We asked them about their views on the environment, health, technology and the economy. In this article, we discuss their views on their education.

‘They don’t teach you the realities’

In our survey, 57% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed their education had prepared them for their future. This means about two fifths (43%) didn’t agree or were uncertain.

Many said school made them “book smart” but didn’t teach essential life skills such as budgeting, taxes, cooking, renting or workplace readiness. As one 23-year-old from Queensland told us:

They don’t teach you the realities of life and being an adult.

This may explain why 61% of young Australians in our study had taken some form of online informal classes, such as a YouTube tutorial. Young people are looking to informal learning for acquiring practical skills such as cooking, household repairs, managing finances, driving and applying for jobs.

Some interviewees discussed how informal learning – outside of formal education places – was a key site for personal development. One interviewee (21) from Western Australia explained how they had learned how to fix computer problems online: “I’ve learnt a great deal from YouTube”. Others talked about turning to Google, TikTok and, more recently, ChatGPT.

A key question here is the reliability of these sources. This is why students need critical thinking and online literacy skills so they can evaluate what they find online.

‘This is so much money’

Young people in our survey echoed wider community concerns about the rising costs of a university education. As one South Australian man (23) told us:

I was looking at the HECS that came along with [certain courses] and I was like, this is crazy, this is so much money.

One woman (19) explained how the fees had been part of the reason why she didn’t want to go to uni.

Truthfully there was nothing at uni that interested me, any careers that it would be leading me to […] also because university is so expensive, I wouldn’t want to get myself in a HECS debt for the rest of my life.

‘Why don’t I know anyone?’

For those who did go to uni, young people spoke about how they were missing out on the social side of education – partly due to COVID lockdowns, the broader move to hybrid/online learning and changes in campus experiences. As one Queensland 19-year-old told us:

For the past year and a half I kind of just went to class and then went home again and I was like, ‘Why don’t I know anyone? Why do I have no friends?’

While some students reported online study saved time, others told us they found it impersonal and disengaging. As one Victorian (23) told us:

It’s more like I’m learning from my laptop, not by a university I’m paying thousands of dollars to.

Another 23-year-old from NSW said students would complain but learn more if they had face-to-face classes:

[online is] more flexible but it means it’s harder to turn off and on […] more traditional university would be nice.

Some young people are worried

One of the key roles of education is to provide pathways to desirable futures. But 40% of young people told us they were worried about their ability to cope with everyday tasks in the future. Almost 80% told us they thought they would be financially worse off than their parents, up from 53% in 2022.

Education alone can’t address all the challenges facing young people, but we can address some key immediate issues. Our findings suggest young people believe education in Australia needs to be more affordable, practical, social and engaging. To do this we need:

more personalised career counselling and up-to-date labour market information for school leavers and university graduates – so young people have clearer ideas about what study or training can lead to particular jobs and careers

better ways of ensuring online learning enables connections and interactions between students and students and teachers – so learning is not as impersonal and there are more opportunities to learn in person or deliberately social online ways

more investment in campus clubs, student wellbeing programs and peer support so young people have more opportunities to make friends and build networks.

Lucas Walsh, Professor of Education Policy and Practice, Youth Studies, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Wednesday, 12 November 2025

The Roman empire built 300,000 kilometres of roads: new study

At its height, the Roman empire covered some 5 million square kilometres and was home to around 60 million people. This vast territory and huge population were held together via a network of long-distance roads connecting places hundreds and even thousands of kilometres apart.

Compared with a modern road, a Roman road was in many ways over-engineered. Layers of material often extended a metre or two into the ground beneath the surface, and in Italy roads were paved with volcanic rock or limestone.

Roads were also furnished with milestones bearing distance measurements. These would help calculate how long a journey might take or the time for a letter to reach a person elsewhere.

Thanks to these long-lasting archaeological remnants, as well as written records, we can build a picture of what the road network looked like thousands of years ago.

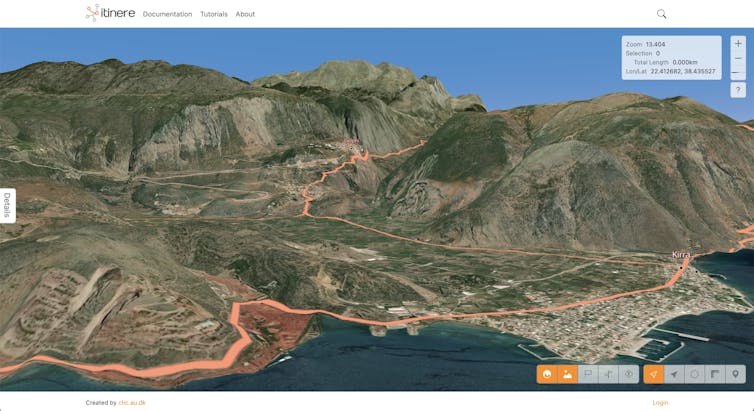

A new, comprehensive map and digital dataset published by a team of researchers led by Tom Brughmans at Aarhus University in Denmark shows almost 300,000 kilometres of roads spanning an area of close to 4 million square kilometres.

The road network

The Itiner-e dataset was pieced together from archaeological and historical records, topographic maps, and satellite imagery.

It represents a substantial 59% increase over the previous mapping of 188,555 kilometres of Roman roads. This is a very significant expansion of our mapped knowledge of ancient infrastructure.

The Via Appia is one of the oldest and most important Roman roads. LivioAndronico2013 / Wikimedia, CC BY

The Via Appia is one of the oldest and most important Roman roads. LivioAndronico2013 / Wikimedia, CC BYAbout one-third of the 14,769 defined road sections in the dataset are classified as long-distance main roads (such as the famous Via Appia that links Rome to southern Italy). The other two-thirds are secondary roads, mostly with no known name.

The researchers have been transparent about the reliability of their data. Only 2.7% of the mapped roads have precisely known locations, while 89.8% are less precisely known and 7.4% represent hypothesised routes based on available evidence.

More realistic roads – but detail still lacking

Itiner-e has improved on past efforts with improved coverage of roads in the Iberian Peninsula, Greece and North Africa, as well as a crucial methodological refinement in how routes are mapped.

Rather than imposing idealised straight lines, the researchers adapted previously proposed routes to fit geographical realities. This means mountain roads can follow winding, practical paths, for example.

Itiner-e includes more realistic terrain-hugging road shapes than some earlier maps. Itiner-e, CC BY

Itiner-e includes more realistic terrain-hugging road shapes than some earlier maps. Itiner-e, CC BYAlthough there is a considerable increase in the data for Roman roads in this mapping, it does not include all the available data for the existence of Roman roads. Looking at the hinterland of Rome, for example, I found great attention to the major roads and secondary roads but no attempt to map the smaller local networks of roads that have come to light in field surveys over the past century.

Itiner-e has great strength as a map of the big picture, but it also points to a need to create localised maps with greater detail. These could use our knowledge of the transport infrastructure of specific cities.

There is much published archaeological evidence that is yet to be incorporated into a digital platform and map to make it available to a wider academic constituency.

Travel time in the Roman empire

Fragment of a Roman milestone erected along the road Via Nova in Jordan. Adam Pažout / Itiner-e, CC BY

Fragment of a Roman milestone erected along the road Via Nova in Jordan. Adam Pažout / Itiner-e, CC BYItiner-e’s map also incorporates key elements from Stanford University’s Orbis interface, which calculates the time it would have taken to travel from point A to B in the ancient world.

The basis for travel by road is assumed to have been humans walking (4km per hour), ox carts (2km per hour), pack animals (4.5km per hour) and horse courier (6km per hour).

This is fine, but it leaves out mule-drawn carriages, which were the major form of passenger travel. Mules have greater strength and endurance than horses, and became the preferred motive power in the Roman empire.

What next?

Itiner-e provides a new means to investigate Roman transportation. We can relate the map to the presence of known cities, and begin to understand the nature of the transport network in supporting the lives of the people who lived in them.

This opens new avenues of inquiry as well. With the network of roads defined, we might be able to estimate the number of animals such as mules, donkeys, oxen and horses required to support a system of communication.

For example, how many journeys were required to communicate the death of an emperor (often not in Rome but in one of the provinces) to all parts of the empire?

Some inscriptions refer to specifically dated renewal of sections of the network of roads, due to the collapse of bridges and so on. It may be possible to investigate the effect of such a collapse of a section of the road network using Itiner-e.

These and many other questions remain to be answered.![]()

Ray Laurence, Professor of Ancient History, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Saturday, 18 October 2025

Are business schools priming students for a world that no longer exists?

Carla Liuzzo, Queensland University of Technology and Mimi Tsai, Queensland University of Technology

Endless economic expansion isn’t sustainable. Scientists are telling us our planet is already beyond its limits, with the risks to communities and the economy made clear in the federal government’s recent climate risk assessment.

Sustainability is a hot topic in Australian business schools. However, teaching about the possible need to limit economic growth – whether directly or indirectly related to sustainability – is uncommon.

Typically, business school teaching is based on concepts of sustainable development and “green growth”. Under these scenarios, we can continue to grow gross domestic product (GDP) globally without continuing to grow emissions – what is known as “decoupling”. It’s a “have your cake and eat it too” promise for sustainability.

Our new research published in the journal Futures shows business students themselves are interested in learning the skills they would need under an alternative post-growth future.

Emerging alternatives to ‘growth is good’

There is mounting evidence of the difficulty of “decoupling” economic growth from emissions growth. The United Nations goals of sustainable development are “in peril”.

This has led to increased interest in no-growth or post-growth economic models and to the movement towards degrowth. Degrowth means shrinking economic production to use less of the world’s resources and avoid climate crisis.

Explicit teaching of degrowth rejects the belief in endless growth. This presents a challenge to traditional concepts in business education, including profit maximisation, competition and the notion of “free markets”.

The issue, and one that degrowth invites students to consider, is that green growth and sustainable development are underpinned by the need for continued economic growth and development. This “growth obsession” is pushing the planet and society to its limits.

Students are keen

Our new study provides a snapshot of students’ interest in alternative systems. It reveals 90% of respondents are open to learning about different economic models.

The study found 96% of students believe business leaders must understand alternative models to continued economic growth. Yet only 15% were aware of any alternatives that may exist. Most (71%) believed viable alternatives exist, but they admitted to lacking sufficient knowledge.

The study had 61 participants currently studying a masters of business administration (MBA) in a top Australian institution.

The research raises the question: if future business leaders are not made aware of alternatives, won’t they continue to assume growth is “inherently good”, and perpetuate the business practices that have pushed humanity beyond planetary boundaries?

The trouble with endless growth

Advocates of the “beyond growth” agenda argue endless growth is not possible. They promote alternate measures of progress to GDP, such as the recent Measuring What Matters report.

Degrowth proposes scaling back the consumption of resources as part of a transition to post-growth economies. Their aim is what economist Tim Jackson calls prosperity without growth. This entails businesses sharing value with communities, and reducing production of things like fast fashion, fast food and fast tech.

It is a rejection of maximising profit in favour of maximising value, based around meeting real needs like housing, food and essential services. Some industries would grow, such as care, education, public transport and renewables. Others may shrink or vanish.

Degrowth and post-growth aren’t alien concepts. There are grassroots movements such as minimalism. Social media abounds with lists of “things I no longer buy”, social enterprises, the right-to-repair movement and community-supported agriculture.

Degrowth also invites students to debate concepts like modern monetary theory, income ratio limits and universal basic income.

The role of business schools

Business schools are doing great work teaching students about changing consumer preferences for green alternatives, new global standards for reporting environmental and social impact, and ways businesses can reduce their environmental impact.

The Australian Business Deans Council in March this year detailed these efforts in its Climate Capabilities Report. This highlighted the need for business schools to produce graduates capable of “balancing business and climate knowledge”.

Our study of Australian business school students shows they are open to learning about degrowth. It challenges the assumption that ideas critical of endless growth would be unwelcome in business schools in Australia.

There is an argument for making explicit degrowth teaching in business schools more accessible because business schools have been criticised for not doing enough to address climate change and social inequality.

Globally, degrowth is starting to be taught explicitly in business schools in Europe, the UK and even the US.

Business schools have long been criticised for a culture of greed and cutthroat competition. As one distinguished professor from the University of Michigan recently put it, “today’s business schools were designed for a world that no longer exists”.

The introduction of no growth or degrowth scenarios to business schools in Australia may go some way to ensuring they are preparing leaders for the future – not priming students for a world that no longer exists.![]()

Carla Liuzzo, Lecturer, Graduate School of Business, Queensland University of Technology and Mimi Tsai, Lecturer, Queensland University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Wednesday, 8 October 2025

How safe is your face? The pros and cons of having facial recognition everywhere

Joanne Orlando, Western Sydney University

Walk into a shop, board a plane, log into your bank, or scroll through your social media feed, and chances are you might be asked to scan your face. Facial recognition and other kinds of face-based biometric technology are becoming an increasingly common form of identification.

The technology is promoted as quick, convenient and secure – but at the same time it has raised alarm over privacy violations. For instance, major retailers such as Kmart have been found to have broken the law by using the technology without customer consent.

So are we seeing a dangerous technological overreach or the future of security? And what does it mean for families, especially when even children are expected to prove their identity with nothing more than their face?

The two sides of facial recognition

Facial recognition tech is marketed as the height of seamless convenience.

Nowhere is this clearer than in the travel industry, where airlines such as Qantas tout facial recognition as the key to a smoother journey. Forget fumbling for passports and boarding passes – just scan your face and you’re away.

In contrast, when big retailers such as Kmart and Bunnings were found to be scanning customers’ faces without permission, regulators stepped in and the backlash was swift. Here, the same technology is not seen as a convenience but as a serious breach of trust.

Things get even murkier when it comes to children. Due to new government legislation, social media platforms may well introduce face-based age verification technology, framing it as a way to keep kids safe online.

At the same time, schools are trialling facial recognition for everything from classroom entry to paying in the cafeteria.

Yet concerns about data misuse remain. In one incident, Microsoft was accused of mishandling children’s biometric data.

For children, facial recognition is quietly becoming the default, despite very real risks.

A face is forever

Facial recognition technology works by mapping someone’s unique features and comparing them against a database of stored faces. Unlike passive CCTV cameras, it doesn’t just record, it actively identifies and categorises people.

This may feel similar to earlier identity technologies. Think of the check-in QR code systems that quickly sprung up at shops, cafes and airports during the COVID pandemic.

Facial recognition may be on a similar path of rapid adoption. However, there is a crucial difference: where a QR code can be removed or an account deleted, your face cannot.

Why these developments matter

Permanence is a big issue for facial recognition. Once your – or your child’s – facial scan is stored, it can stay in a database forever.

If the database is hacked, that identity is compromised. In a world where banks and tech platforms may increasingly rely on facial recognition for access, the stakes are very high.

What’s more, the technology is not foolproof. Mis-identifying people is a real problem.

Age-estimating systems are also often inaccurate. One 17-year-old might easily be classified as a child, while another passes as an adult. This may restrict their access to information or place them in the wrong digital space.

A lifetime of consequences

These risks aren’t just hypothetical. They already affect lives. Imagine being wrongly placed on a watchlist because of a facial recognition error, leading to delays and interrogations every time you travel.

Or consider how stolen facial data could be used for identity theft, with perpetrators gaining access to accounts and services.

In the future, your face could even influence insurance or loan approvals, with algorithms drawing conclusions about your health or reliability based on photo or video.

Facial recognition does have some clear benefits, such as helping law enforcement identify suspects quickly in crowded spaces and providing convenient access to secure areas.

But for children, the risks of misuse and error stretch across a lifetime.

So, good or bad?

As it stands, facial recognition would seem to carry more risks than rewards. In a world rife with scams and hacks, we can replace a stolen passport or drivers’ licence, but we can’t change our face.

The question we need to answer is where we draw the line between reckless implementation and mandatory use. Are we prepared to accept the consequences of the rapid adoption of this technology?

Security and convenience are important, but they are not the only values at stake. Until robust, enforceable rules around safety, privacy and fairness are firmly established, we should proceed with caution.

So next time you’re asked to scan your face, don’t just accept it blindly. Ask: why is this necessary? And do the benefits truly outweigh the risks – for me, and for everyone else involved?![]()

Joanne Orlando, Researcher, Digital Wellbeing, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Saturday, 30 August 2025

What does Steve Smith’s Stateside signing mean for cricket in the US – and Australia?

Steve Smith, one of this generation’s finest batters, has conquered much of the cricketing world during his career, and he now has set his sights on a new frontier: the United States.

Yes, Smith has signed to play Twenty 20 (T20) cricket for the Washington Freedom, which happens to be coached by former Australian great Ricky Ponting.

Washington is one of six teams in Major League Cricket (MLC), which began in 2023. The Freedom finished third in the inaugural season, won by New York.

The 2024 season will begin in July before the US co-hosts the T20 World Cup with the West Indies.

A number of established cricket stars have already played in the US league, including Quinton de Kock of South Africa, Nicholas Pooran from the West Indies, Trent Boult from New Zealand and Australians Marcus Stoinis and Aaron Finch.

Looking ahead, T20 cricket has been included for the Los Angeles 2028 Olympic Games.

So, why is cricket suddenly interested in the US – and does this interest go both ways?

Cricket in the US: what’s the go?

Cricket is slowly becoming better known in the US.

Firstly, it is because of the rising South Asian population who mostly love their cricket.

It is a growing and affluent professional community – the South Asian diaspora is growing at a rapid rate across North America to the point that when you fly into most large US cities, you can spot cricket pitches.

Many South Asian immigrants to the US (and Canada) are engineers, doctors and entrepreneurs with good educations and professional jobs – Indian-Americans are the most affluent group in America by median household income, while Sri Lankans and Pakistanis are two of the eight wealthiest segments.

In terms of education, 70% of Indian-Americans have at least a Bachelor’s degree, compared to the US average of 28%.

A lot of this affluence is ploughed into supporting local cricket leagues in the US and watching the MLC.

In terms of participation, cricket is still very much a niche sport in the US, with about 200,000 registered players. However, this has grown from around 30,000 registered players in 2006, with emigration from South Asia driving the lion’s share of growth.

Consuming cricket anytime, anywhere

Secondly, live streaming has taken off worldwide in recent years, allowing Indians in the US to watch India Premier League (IPL) games back home, and Indians in India to live stream MLC matches.

According to Chris Muldoon, chief strategy officer of Cricket NSW, there are more than 4 million subscribers to Willow TV’s cricket-only streaming service throughout North America.

This means it is easy for most cricket fans can consume what they want, when they want it.

The growth of cricket franchises

Thirdly, IPL franchises are launching clubs and leagues around the world – in South Africa, the UAE and the US – to grow the sport and to attract talent and revenue to their respective franchises.

There is a strong IPL presence across many of the domestic T20 competitions that have launched in recent years, including in MLS where four IPL franchises are involved with the foundation clubs in New York, Dallas, Los Angeles and Seattle.

This is a big shift in cricket governance, as it is not just the cricket boards of Australia, England & Wales and India calling the shots on schedules – it is now the IPL franchises too.

What does this mean for Australian cricket?

So, how does all of this affect elite cricket in Australia?

Australian cricketers have been competing in T20 competitions around the world for years now, with Cricket Australia occasionally having to step in to reduce the workloads of some of its best players.

Now the MLC will force governing bodies and players to react to another competition in a packed cricket calendar.

According to Muldoon, the opportunity in the US is too big to ignore. He says:

The US is the world’s most sophisticated and competitive sports and media market and Major League Cricket presents the most exciting and challenging opportunity in world cricket.

The proliferation of franchise T20 cricket around the globe, much of it driven by the commercial success of the IPL as well as changing preferences of consumers, is changing the way cricket is consumed. And it is bringing new revenue into the sport – which in turn is making it increasingly attractive to the world’s best players and coaches to be a part of these growing franchise leagues around the world on an almost full-time basis.

Will cricket really take hold in the US?

So does Smith’s signing indicate a cricket revolution? Does the US aspire to be a cricket nation?

Probably not in terms of Test cricket, but in the US, the shortened format of T20 is possibly appealing.

This is largely driven by the South Asian diaspora who have migrated to North America, and T20 is the format that has the consumer appeal to attract eyeballs – and broadcast partners. The addition of cricket as an Olympic sport for Los Angeles in 2028 may also add to the sport’s exposure.![]()

Tim Harcourt, Industry Professor and Chief Economist, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Thursday, 7 August 2025

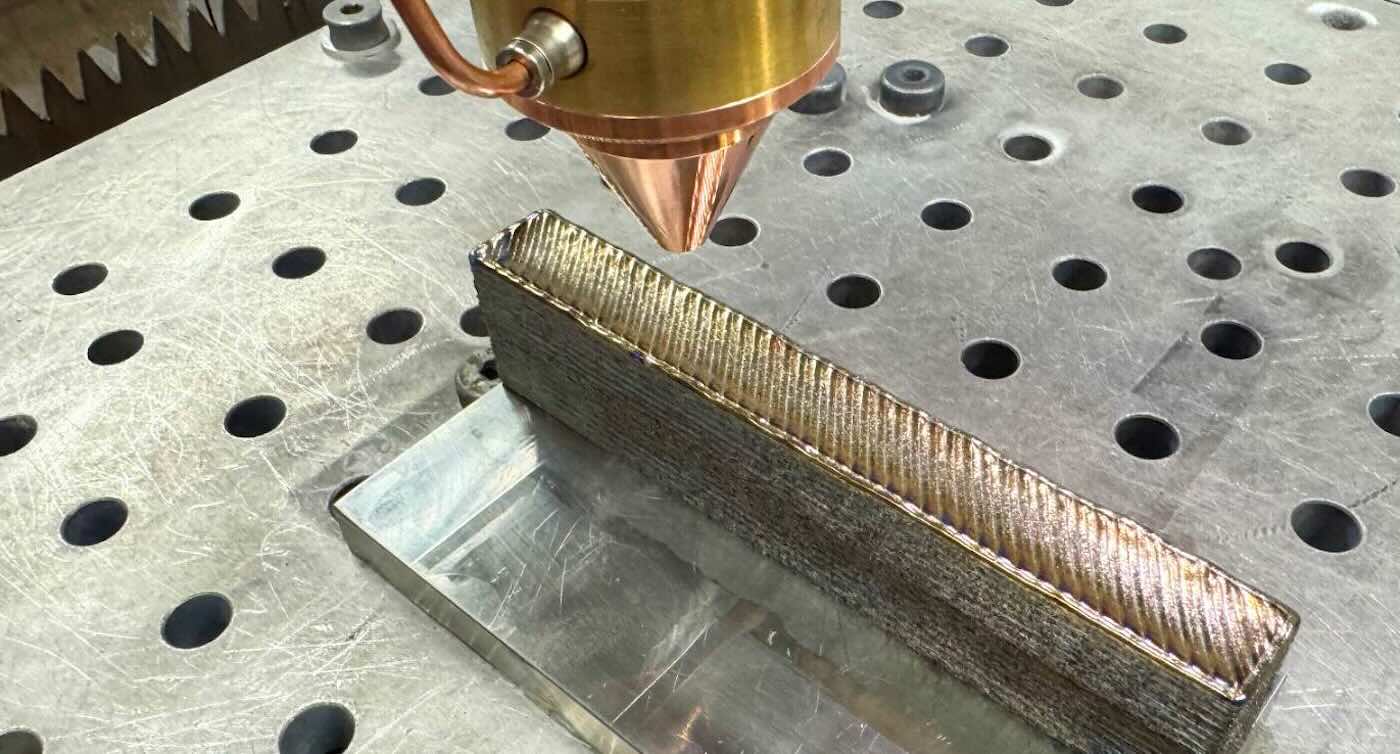

New 3D-Printed Titanium Alloy is Stronger Than the Standard – Yet 30% Cheaper

Ryan Brooke inspects a sample of the new titanium – Photo by Michael Quin (RMIT University)

Ryan Brooke inspects a sample of the new titanium – Photo by Michael Quin (RMIT University) Photo credit: RMIT

Photo credit: RMITThursday, 12 June 2025

Australia reach World Cup as Palestinian dreams ended

Tuesday, 13 May 2025

Australia and North America have long fought fires together – but new research reveals that has to change

Climate change is lengthening fire seasons across much of the world. This means the potential for wildfires at any time of the year, in both hemispheres, is increasing.

That poses a problem. Australia regularly shares firefighting resources with the United States and Canada. But these agreements rest on the principle that when North America needs these personnel and aircraft, Australia doesn’t, and vice versa. Climate change means this assumption no longer holds.

The devastating Los Angeles wildfires in January, the United States winter, show how this principle is being tested. The US reportedly declined Australia’s public offer of assistance because Australia was in the midst of its traditional summer fire season. Instead, the US sought help from Canada and Mexico.

But to what extent do fire seasons in Australia and North America actually overlap? Our new research examined this question. We found an alarming increase in the overlap of the fire seasons, suggesting both regions must invest far more in their own permanent firefighting capacity.

What we did

We investigated fire weather seasons – that is, the times of the year when atmospheric conditions such as temperature, humidity, rainfall and wind speed are conducive to fire.

The central question we asked was: how many days each year do fire weather seasons in Australia and North America overlap?

To determine this, we calculated the length of the fire weather seasons in the two regions in each year, and the number of days when the seasons occur at the same time. We then analysed reconstructed historical weather data to assess fire-season overlap for the past 45 years. We also analysed climate model data to assess changes out to the end of this century.

And the result? On average, fire weather occurs in both regions simultaneously for about seven weeks each year. The greatest risk of overlap occurs in the Australian spring – when Australia’s season is beginning and North America’s is ending.

The overlap has increased by an average of about one day per year since 1979. This might not sound like much. But it translates to nearly a month of extra overlap compared to the 1980s and 1990s.

The increase is driven by eastern Australia, where the fire weather season has lengthened at nearly twice the rate of western North America. More research is needed to determine why this is happening.

Longer, hotter, drier

Alarmingly, as climate change worsens and the atmosphere dries and heats, the overlap is projected to increase.

The extent of the overlap varied depending on which of the four climate models we used. Assuming an emissions scenario where global greenhouse gas emissions begin to stabilise, the models projected an increase in the overlap of between four and 29 days a year.

What’s behind these differences? We think it’s rainfall. The models project quite different rainfall trends over Australia. Those projecting a dry future also project large increases in overlapping fire weather. What happens to ours and North America’s rainfall in the future will have a large bearing on how fire seasons might change.

While climate change will dominate the trend towards longer overlapping fire seasons, El Niño and La Niña may also play a role.

These climate drivers involve fluctuations every few years in sea surface temperature and air pressure in part of the Pacific Ocean. An El Niño event is associated with a higher risk of fire in Australia. A La Niña makes longer fire weather seasons more likely in North America.

There’s another complication. When an El Niño occurs in the Central Pacific region, this increases the chance of overlap in fire seasons of North America and Australia. We think that’s because this type of El Niño is especially associated with dry conditions in Australia’s southeast, which can fuel fires.

But how El Niño and La Niña will affect fire weather in future is unclear. What’s abundantly clear is that global warming will lead to more overlap in fire seasons between Australia and North America – and changes in Australia’s climate are largely driving this trend.

Looking ahead

Firefighters and their aircraft are likely to keep crossing the Pacific during fire emergencies.

But it’s not difficult to imagine, for example, simultaneous fires occurring in multiple Australian states during spring, before any scheduled arrival of aircraft from the US or Canada. If North America is experiencing late fires that year and cannot spare resources, Australia’s capabilities may be exceeded.

Likewise, even though California has the largest civil aerial firefighting fleet in the world, the recent Los Angeles fires highlighted its reliance on leased equipment.

Fire agencies are becoming increasingly aware of this clash. And a royal commission after the 2019–20 Black Summer fires recommended Australia develop its own fleet of firefighting aircraft.

Long, severe fire seasons such as Black Summer prompted an expansion of Australia’s permanent aerial firefighting fleet, but more is needed.

As climate change accelerates, proactive fire management, such as prescribed burning, is also important to reduce the risk of uncontrolled fire outbreaks.![]()

Doug Richardson, Research Associate in Climate Science, UNSW Sydney and Andreia Filipa Silva Ribeiro, Climate Researcher, Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research-UFZ

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Monday, 12 May 2025

Surfer Conquers Biggest Waves in the World Despite Only Having One Leg

Pegleg Bennett during a surf session at Perranporth Beach – credit, William Dax, SWNS

Pegleg Bennett during a surf session at Perranporth Beach – credit, William Dax, SWNS Pegleg Bennett during a surf session at Perranporth Beach – credit, William Dax, SWNS

Pegleg Bennett during a surf session at Perranporth Beach – credit, William Dax, SWNSMonday, 5 May 2025

Hockey: India women end Australia tour with 1-0 win

Tuesday, 22 April 2025

Not just the stadium: what Brisbane Olympic organisers are planning for

Brisbane was awarded the Olympics and Paralympics more than 1,300 days ago, and much has happened in between.

On Tuesday, upbeat Queensland premier David Crisafulli revealed the 2032 Brisbane Olympic and Paralympic Games plan.

This came after a 100-day review by the Games Independent Infrastructure and Coordination Authority (GIICA).

More than 5,000 submissions were received from the general public. The review included topics such as precincts and transport systems, while evaluating topics such as demand and affordability.

So, what’s going to be happening in Queensland before, during and after the games?

The main event: venues

Get ready for the likes of Taylor Swift, Pink, Coldplay and others to finally come to Brisbane with the announcement of a new world-class 63,000 seat Olympic Stadium to be built in Victoria Park in Brisbane.

All indications are major codes, such as the Australian Football League (AFL) and cricket, are also very pleased, as they will have a new home replacing the outdated Gabba.

Other venues, both in South East Queensland and in regional areas such as the Gold Coast, Sunshine Coast, Cairns and Townsville, were also outlined.

One of these is a new 25,000-seat swimming complex at Spring Hill, making it one of the world’s best facilities.

As Australia is a swimming powerhouse with major medal hauls expected in 2032, this news was well received.

However, a few of the GIICA recommendations were not accepted. The government has announced rowing will take place in Rockhampton – and not interstate – in an existing flat water venue.

Why the delays?

There had been plenty of criticism of the decision-making delays on facilities and their locations. But the Queensland government’s 2032 Games Delivery Plan indicates there is no need to panic.

Previously, the International Olympic Committee chose a host city seven years out, but under new protocols, Los Angeles in 2028 and Brisbane in 2032 have been given 11 years to finalise planning.

Previous Australian games (Melbourne in 1956 and Sydney in 2000) only had seven years to organise their events.

In the case of Melbourne, several controversies erupted due to the costs of building a new stadium at proposed sites such as the Royal Showgrounds or Princes Park.

Eventually, politics and economics intervened, and a refurbished Melbourne Cricket Ground within an impressive Olympic Park precinct was agreed on.

In the case of Sydney, the original idea back in the 1960s was to host either the Commonwealth Games or the Olympic Games at Moore Park, an inner-city region home to the Sydney Cricket Ground, a golf course and parklands.

But many local residents were vehemently opposed to that suggestion, so other sites were sought.

Eventually, the uninhabited Homebush site was chosen in 1973. This was an unexpected decision because it was the most polluted environment in Australia and its remediation, however noble, would be an enormous challenge.

And so it proved.

When Sydney was awarded the games in 1993, timeline pressures prompted organisers to bulldoze toxic waste into mounds on site, where they were covered with clay and landscaped.

Meanwhile, the promised remediation of toxic waterways in Homebush Bay never proceeded.

All that said, the Sydney games provided tangible legacies. The Olympic Village is now the suburb of Newington, there are parklands and cycle paths for visitors, and from a sport perspective several facilities remain in use today. In 2024, more than 10 million people visited the Sydney Olympic Park precinct, attending sport, concerts, or participating in social activities.

Opportunities and hurdles

The initial hiccups associated with the Brisbane games have resulted in some interesting and healthy debate, but this major project now has a positive vibe.

There is more than enough time to build the new facilities (including the athletes’ villages), upgrade existing ones, build the necessary transport infrastructure, and ensure community engagement.

The “Queensland way” seems not only to be referring to a better games, but also the legacy that comes with it.

Generational infrastructure (for example, the upgrade of transport connectivity), housing (such as the conversion of the RNA Showgrounds and a multimillion dollar investment into grassroots clubs can enable the next generations of Queenslanders to compete.

Tourism and regionalisation of the games through a 20-year plan should ensure the impact of the games goes far beyond 2032.

Some fine-tuning is expected the next few years though, and there may be unforeseen issues that arise – here are some.

1. Beyond the 31 core sports that must feature, will new sports necessitate changes or additions to proposed venues? Host cities are now allowed to have 4-5 sports added to the program which could cause increases to the budget.

2. Will the federal government fund the games on the currently agreed 50-50 basis with the Queensland government? This currently sits at around $7 billion split two ways, but it is likely to rise based on cost over-runs on virtually all major builds across Australia.

3. Will there be some tweaking of chosen venues due to local issues, lobbying by Olympic sports, political decisions and other factors?

4. Will a global health issue (such as COVID during the Tokyo 2021 games) or a major world problem (such as the current Gaza or Ukraine conflicts) impact the games in some way?

The Brisbane games are following the footsteps of Melbourne 1956 (affectionately referred to as the “friendly games”) and Sydney 2000 (the “best games ever”).

The eventual Brisbane label has yet to be determined. But the Brisbane games will no doubt add to the Olympic folklore of Australia in their own unique way.![]()

H. Björn Galjaardt, PhD Candidate, The University of Queensland; Daryl Adair, Associate Professor of Sport Management, University of Technology Sydney, and Richard Baka, Honorary Professor, School of Kinesiology, Western University, London, Canada; Adjunct Fellow, Olympic Scholar and Co-Director of the Olympic and Paralympic Research Centre, Institute for Health and Sport, Victoria University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.