Monday, 16 February 2026

Winter Olympics face an existential chill from climate change

Saturday, 14 February 2026

Winter Olympics face an existential chill from climate change

.jpg)

Sunday, 1 February 2026

World’s Most Northern Electric Ferry Now Sailing in Frigid -13°F Temps (-25°C)

Friday, 9 January 2026

Millions of hectares are still being cut down every year. How can we protect global forests?

David Clode/Unsplash, CC BY

Kate Dooley, The University of Melbourne

David Clode/Unsplash, CC BY

Kate Dooley, The University of Melbourne

Ahead of the United Nations climate summit in Belém last month, Brazil’s President Lula da Silva urged world leaders to agree to roadmaps away from fossil fuels and deforestation and pledge the resources to meet these goals.

After failing to secure consensus, COP president Andre Corrêa do Lago announced these roadmaps as a voluntary initiative. Brazil will report back on progress at next year’s UN climate summit, COP31, when it hands the presidency to Turkey and Australia chairs the negotiations.

Why now?

These goals originate in the outcomes of the first global stocktake of the world’s progress towards the Paris Agreement goals, undertaken in 2023.

At the COP28 talks in Dubai in that year, there was an agreement to transition away from fossil fuels and to halt and reverse deforestation and forest degradation by 2030.

Yet achieving these goals relies on a “just transition”, where no country is left behind in the transition to a low-carbon future, including a “core package” of public finance to address climate adaptation, and loss and damage. The Belém outcome fell short.

Forests need urgent protection

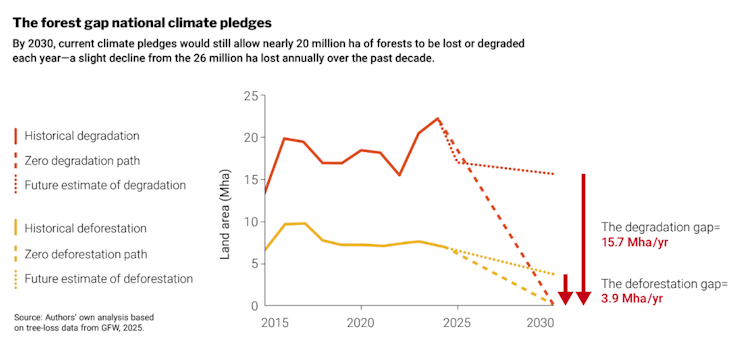

Forest loss and degradation is continuing, at an average rate of 25 million hectares a year over the last decade, according to the Global Forest Watch. This is 63% higher than the rate needed to meet existing targets to halt and reverse forest loss by 2030. Yet the climate pledges submitted for the Belém COP remain far off track from this goal.

In the 2025 Land Gap Report, my colleagues and I calculated the scale of this “forest gap” – the gap between 2030 targets and the plans countries are putting forward in their climate pledges.

We show the pledges submitted up until this year’s climate summit would cut deforestation by less than 50% by 2030, meaning forests spanning almost 4 million hectares would still be cut down. The pledges would lead to forest degradation – where the ecological integrity of a forest area is diminished – of almost 16 million hectares. This is only a 10% reduction on current rates.

Together, this equates to an anticipated “forest gap” of around 20 million hectares expected to be lost or degraded each year by 2030. That’s about twice the size of South Korea.

While this underscores the inadequacy of commitments, the analysis is based on pledges submitted up to the start of November 2025, at which point only 40% of countries had submitted an updated plan. Major pledges submitted during COP31, such as from the European Union and China, don’t change this analysis.

This graph shows that deforestation will only slightly decline to 2030. The Land Gap Report, author supplied., CC BY-ND

This graph shows that deforestation will only slightly decline to 2030. The Land Gap Report, author supplied., CC BY-NDForest wins in Belém

A new fund for forest conservation called the Tropical Forests Forever Facility was launched in Brazil, attracting $US6.7 billion in pledges ($A9.9 billion).

The forest fund focuses on tropical deforestation, the leading cause of emissions from forest loss. But it has a key weakness: the limited monitoring of forest degradation, which could allow countries to receive payments while still logging primary forests.

The fund will establish a science committee and plans to revise monitoring indicators over the next three years, creating an opportunity to strengthen its ability to protect tropical forests.

The COP30 leaders’ summit also saw the launch of a historic pledge of $US1.8 billion ($A2.7 billion) to support conservation and recognition of 160 million hectares of Indigenous Peoples’ and local communities’ territories in tropical forest countries.

But global action on forests needs to extend beyond the tropics. Across both deforestation and forest degradation, countries in the global north are responsible for over half of global tree cover loss over the past decade.

Beyond tropical forests

A global accountability framework on forests is needed to increase ambition on climate action, including in countries and regions with extensive forests outside of the tropics, such as Australia, Canada and Europe.

In these regions, industrial logging is a major driver of tree-cover loss but receives far less political attention than tropical deforestation. Wide gaps in reporting – between deforestation and degradation – mean logging-related degradation often goes unreported.

In a recent report, only 59 countries said they monitor forest degradation. Of these, almost three-quarters are tropical forest countries.

The IUCN World Conservation Congress which convened in Abu Dhabi this year prior to the climate talks, passed a motion on delivering equitable accountability and means of implementation for international forest protection goals. This arose from a recognised need to promote greater equity between forest protection standards across countries.

All of this points to an urgent need to tackle accountability in global forest governance. The forest roadmap to be developed for COP31 in Turkey could help drive stronger alignment and transparency across UN processes – from the UN Forum on Forests’ 2017–2030 plan to the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework’s 2030 target to halt and reverse biodiversity loss.

Australia could lead on forests

Australia could help shape global forest ambition in the year ahead. It is currently the only country whose emissions pledge promises to halt and reverse deforestation and degradation by 2030 – a clear signal that developed countries must lead.

As President of Negotiations at COP31, Australia can also work to bring Brazil’s fossil-fuel and forest roadmaps into formal negotiations. But this depends on two things: credible leadership from developed countries and long-overdue climate finance. As a deforestation hotspot with ongoing native forest logging, Australia has considerable work to do to meet this responsibility.![]()

Kate Dooley, Senior Research Fellow, School of Geography, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Wednesday, 24 December 2025

Over 600 Lakes, Ponds, Reservoirs Restored Across the Whole of India by Divinely-Inspired Nonprofit

Monday, 22 December 2025

Arctic endures year of record heat

.jpg)

Saturday, 29 November 2025

Land, air and sea — India works closely with Sri Lanka as 'Operation Sagar Bandhu' goes full throttle

Friday, 28 November 2025

Delhi’s air quality deteriorates again, AQI climbs to 385 as cold wave deepens pollution crisis

Thursday, 9 October 2025

The Ganges River is drying faster than ever – here’s what it means for the region and the world

Mehebub Sahana, University of Manchester

The Ganges, a lifeline for hundreds of millions across South Asia, is drying at a rate scientists say is unprecedented in recorded history. Climate change, shifting monsoons, relentless extraction and damming are pushing the mighty river towards collapse, with consequences for food, water and livelihoods across the region.

For centuries, the Ganges and its tributaries have sustained one of the world’s most densely populated regions. Stretching from the Himalayas to the Bay of Bengal, the whole river basin supports over 650 million people, a quarter of India’s freshwater, and much of its food and economic value. Yet new research reveals the river’s decline is accelerating beyond anything seen in recorded history.

Stretches of river that once supported year-round navigation are now impassable in summer. Large boats that once travelled the Ganges from Bengal and Bihar through Varanasi and Allahabad now run aground where water once flowed freely. Canals that used to irrigate fields for weeks longer a generation ago now dry up early. Even some wells that protected families for decades are yielding little more than a trickle.

Global climate models have failed to predict the severity of this drying, pointing to something deeply unsettling: human and environmental pressures are combining in ways we don’t yet understand.

Water has been diverted into irrigation canals, groundwater has been pumped for agriculture, and industries have proliferated along the river’s banks. More than a thousand dams and barrages have radically altered the river itself. And as the world warms, the monsoon which feeds the Ganges has grown increasingly erratic. The result is a river system increasingly unable to replenish itself.

Melting glaciers, vanishing rivers

At the river’s source high in the Himalayas, the Gangotri glacier has retreated nearly a kilometre in just two decades. The pattern is repeating across the world’s largest mountain range, as rising temperatures are melting glaciers faster than ever.

Initially, this brings sudden floods from glacial lakes. In the long-run, it means far less water flowing downstream during the dry season.

These glaciers are often termed the “water towers of Asia”. But as those towers shrink, the summer flow of water in the Ganges and its tributaries is dwindling too.

Humans are making things worse

The reckless extraction of groundwater is aggravating the situation. The Ganges-Brahmaputra basin is one of the most rapidly depleting aquifers in the world, with water levels falling by 15–20 millimeters each year. Much of this groundwater is already contaminated with arsenic and fluoride, threatening both human health and agriculture.

The role of human engineering cannot be ignored either. Projects like the Farakka Barrage in India have reduced dry-season flows into Bangladesh, making the land saltier and threatening the Sundarbans, the world’s largest mangrove forest. Decisions to prioritise short-term economic gains have undermined the river’s ecological health.

Across northern Bangladesh and West Bengal, smaller rivers are already drying up in the summer, leaving communities without water for crops or livestock. The disappearance of these smaller tributaries is a harbinger of what may happen on a larger scale if the Ganges itself continues its downward spiral. If nothing changes, experts warn that millions of people across the basin could face severe food shortages within the next few decades.

Saving the Ganges

The need for urgent, coordinated action cannot be overstated. Piecemeal solutions will not be enough. It’s time for a comprehensive rethinking of how the river is managed.

That will mean reducing unsustainable extraction of groundwater so supplies can recharge. It will mean environmental flow requirements to keep enough water in the river for people and ecosystems. And it will require improved climate models that integrate human pressures (irrigation and damming, for example) with monsoon variability to guide water policy.

Transboundary cooperation is also a must. India, Bangladesh and Nepal must do better at sharing data, managing dams, and planning for climate change. International funding and political agreements must treat rivers like the Ganges as global priorities. Above all, governance must be inclusive, so local voices shape river restoration efforts alongside scientists and policymakers.

The Ganges is more than a river. It is a lifeline, a sacred symbol, and a cornerstone of South Asian civilisation. But it is drying faster than ever before, and the consequences of inaction are unthinkable. The time for warnings has passed. We must act now to ensure the Ganges continues to flow – not just for us, but for generations to come.![]()

Mehebub Sahana, Leverhulme Early Career Fellow, Geography, University of Manchester

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Friday, 12 September 2025

TinyML: The Small Technology Tackling the Biggest Climate Challenge

Wednesday, 10 September 2025

What will happen to the legal status of ‘sinking’ nations when their land is gone?

Small island nations such as Tuvalu, Kiribati, the Maldives and Marshall Islands are particularly vulnerable to climate change. Rising seas, stronger storms, freshwater shortages and damaged infrastructure all threaten their ability to support life.

Some islands even face the grim possibility of being abandoned or sinking beneath the ocean. This raises an unprecedented legal question: can these small island nations still be considered states if their land disappears?

The future status of these nations as “states” matters immensely. Should the worst happen, their populations will lose their homes and sources of income. They will also lose their way of life, identity, culture, heritage and communities.

At the same time, the loss of statehood could strip these nations of control over valuable natural resources and even cost them their place in international organisations such as the UN. Understandably, they are working hard to make sure this outcome is avoided.

Beyond affirming that “the statehood and sovereignty of Tuvalu will continue … notwithstanding the impact of climate change-related sea-level rise”, Australia has committed to accepting Tuvaluan citizens who seek to emigrate and start their lives afresh on safer ground.

Facing the threat of physical disappearance, Tuvalu has also begun digitising itself. This has involved moving its government services online, as well as recreating its land and archiving its culture virtually.

The aim is for Tuvalu to continue existing as a state even when climate change has forced its population into exile and rising seas have done away with its land. It says it will be the world’s first digital nation.

Elsewhere, in the Maldives, engineering solutions are being tested. These include raising island heights artificially to withstand the disappearance of territory. Other initiatives, such as the Rising Nations Initiative, are seeking to safeguard the sovereignty of Pacific island nations in the face of climate threats.

But how will the future statehood of small island nations be determined legally?

International law’s position

Traditionally, international law requires four elements for a state to exist. These are the existence of population, territory, an effective and independent government and the capacity to engage in international relations.

With climate change threatening to render the land of small island nations unliveable or rising seas covering them entirely, both population and territory will be lost. Effective and independent government will also become inoperative. On the face of it, all the elements required for statehood would cease to exist.

But international law does recognise that once a state is established it continues to exist even if some of the elements of statehood are compromised. For instance, so-called failed states such as Somalia or Yemen are still regarded as states despite lacking an effective government – one of the core elements required under international law.

However, the threats posed to the statehood of small island nations by climate change are unprecedented and severe. They are also very likely to be permanent. This makes it unclear whether international law can extend this flexibility to sinking island nations.

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) recently issued its advisory opinion on the obligations of states in respect of climate change. The ICJ addressed a wide range of issues concerning the legal obligations of states in the context of climate change. This included the future statehood of small island nations.

In this regard, the ICJ acknowledged that climate change could threaten the existence of small islands and low-lying coastal states. But it concluded its discussion with a single, rather cryptic sentence: “once a state is established, the disappearance of one of its constituent elements would not necessarily entail the loss of its statehood.”

What exactly did the court mean by this remark? Unfortunately, the answer is not entirely clear. On the one hand, the decision seems to confirm the traditional flexible approach of international law to statehood.

In their separate opinions, some of the court’s judges interpreted this sentence as extending the flexibility previously applied in other contexts – such as failed states – also to the situation of sinking island nations. In other words, a state could retain its legal existence even if it disappears beneath rising seas.

At the same time, a closer reading of the decision suggests that the court stopped short of explicitly confirming that the flexibility of the term “statehood” could be stretched so far as to mean a state could exist even if completely submerged under the seas.

The court noted only that the disappearance of “one element … would not necessarily” result in the loss of statehood. But in the case of sinking island nations it is likely that all key elements – population, territory, government and ability to enter into international relations – would disappear.

For now, the ICJ has left the matter open. The decision points to flexibility, but it avoids the definitive statement that many vulnerable nations had hoped for. The legal future of sinking islands remains uncertain.![]()

Avidan Kent, Professor of Law, University of East Anglia and Zana Syla, PhD Candidate in the School of Law, University of East Anglia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tuesday, 26 August 2025

Wildfires in Spain signal growing climate risks for Europe, expert warns

Wednesday, 2 July 2025

Extreme heat, storms take toll at Club World Cup

Tuesday, 24 June 2025

China Achieves ‘Excellent’ Water Quality in 90% of Rivers and Lakes, Now Looks to Improve Whole Ecosystems

The Yulong River – credit, Qeqertaq, CC 3.0. BY-SA

The Yulong River – credit, Qeqertaq, CC 3.0. BY-SATuesday, 17 June 2025

12-Year-old Girl Plants 150,000 Trees in India, Becoming a Reforestation Leader

Saturday, 14 June 2025

Above-average monsoon drives rural demand for Indian automobile sector: HSBC

Tuesday, 13 May 2025

Australia and North America have long fought fires together – but new research reveals that has to change

Climate change is lengthening fire seasons across much of the world. This means the potential for wildfires at any time of the year, in both hemispheres, is increasing.

That poses a problem. Australia regularly shares firefighting resources with the United States and Canada. But these agreements rest on the principle that when North America needs these personnel and aircraft, Australia doesn’t, and vice versa. Climate change means this assumption no longer holds.

The devastating Los Angeles wildfires in January, the United States winter, show how this principle is being tested. The US reportedly declined Australia’s public offer of assistance because Australia was in the midst of its traditional summer fire season. Instead, the US sought help from Canada and Mexico.

But to what extent do fire seasons in Australia and North America actually overlap? Our new research examined this question. We found an alarming increase in the overlap of the fire seasons, suggesting both regions must invest far more in their own permanent firefighting capacity.

What we did

We investigated fire weather seasons – that is, the times of the year when atmospheric conditions such as temperature, humidity, rainfall and wind speed are conducive to fire.

The central question we asked was: how many days each year do fire weather seasons in Australia and North America overlap?

To determine this, we calculated the length of the fire weather seasons in the two regions in each year, and the number of days when the seasons occur at the same time. We then analysed reconstructed historical weather data to assess fire-season overlap for the past 45 years. We also analysed climate model data to assess changes out to the end of this century.

And the result? On average, fire weather occurs in both regions simultaneously for about seven weeks each year. The greatest risk of overlap occurs in the Australian spring – when Australia’s season is beginning and North America’s is ending.

The overlap has increased by an average of about one day per year since 1979. This might not sound like much. But it translates to nearly a month of extra overlap compared to the 1980s and 1990s.

The increase is driven by eastern Australia, where the fire weather season has lengthened at nearly twice the rate of western North America. More research is needed to determine why this is happening.

Longer, hotter, drier

Alarmingly, as climate change worsens and the atmosphere dries and heats, the overlap is projected to increase.

The extent of the overlap varied depending on which of the four climate models we used. Assuming an emissions scenario where global greenhouse gas emissions begin to stabilise, the models projected an increase in the overlap of between four and 29 days a year.

What’s behind these differences? We think it’s rainfall. The models project quite different rainfall trends over Australia. Those projecting a dry future also project large increases in overlapping fire weather. What happens to ours and North America’s rainfall in the future will have a large bearing on how fire seasons might change.

While climate change will dominate the trend towards longer overlapping fire seasons, El Niño and La Niña may also play a role.

These climate drivers involve fluctuations every few years in sea surface temperature and air pressure in part of the Pacific Ocean. An El Niño event is associated with a higher risk of fire in Australia. A La Niña makes longer fire weather seasons more likely in North America.

There’s another complication. When an El Niño occurs in the Central Pacific region, this increases the chance of overlap in fire seasons of North America and Australia. We think that’s because this type of El Niño is especially associated with dry conditions in Australia’s southeast, which can fuel fires.

But how El Niño and La Niña will affect fire weather in future is unclear. What’s abundantly clear is that global warming will lead to more overlap in fire seasons between Australia and North America – and changes in Australia’s climate are largely driving this trend.

Looking ahead

Firefighters and their aircraft are likely to keep crossing the Pacific during fire emergencies.

But it’s not difficult to imagine, for example, simultaneous fires occurring in multiple Australian states during spring, before any scheduled arrival of aircraft from the US or Canada. If North America is experiencing late fires that year and cannot spare resources, Australia’s capabilities may be exceeded.

Likewise, even though California has the largest civil aerial firefighting fleet in the world, the recent Los Angeles fires highlighted its reliance on leased equipment.

Fire agencies are becoming increasingly aware of this clash. And a royal commission after the 2019–20 Black Summer fires recommended Australia develop its own fleet of firefighting aircraft.

Long, severe fire seasons such as Black Summer prompted an expansion of Australia’s permanent aerial firefighting fleet, but more is needed.

As climate change accelerates, proactive fire management, such as prescribed burning, is also important to reduce the risk of uncontrolled fire outbreaks.![]()

Doug Richardson, Research Associate in Climate Science, UNSW Sydney and Andreia Filipa Silva Ribeiro, Climate Researcher, Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research-UFZ

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.