Wednesday, 18 February 2026

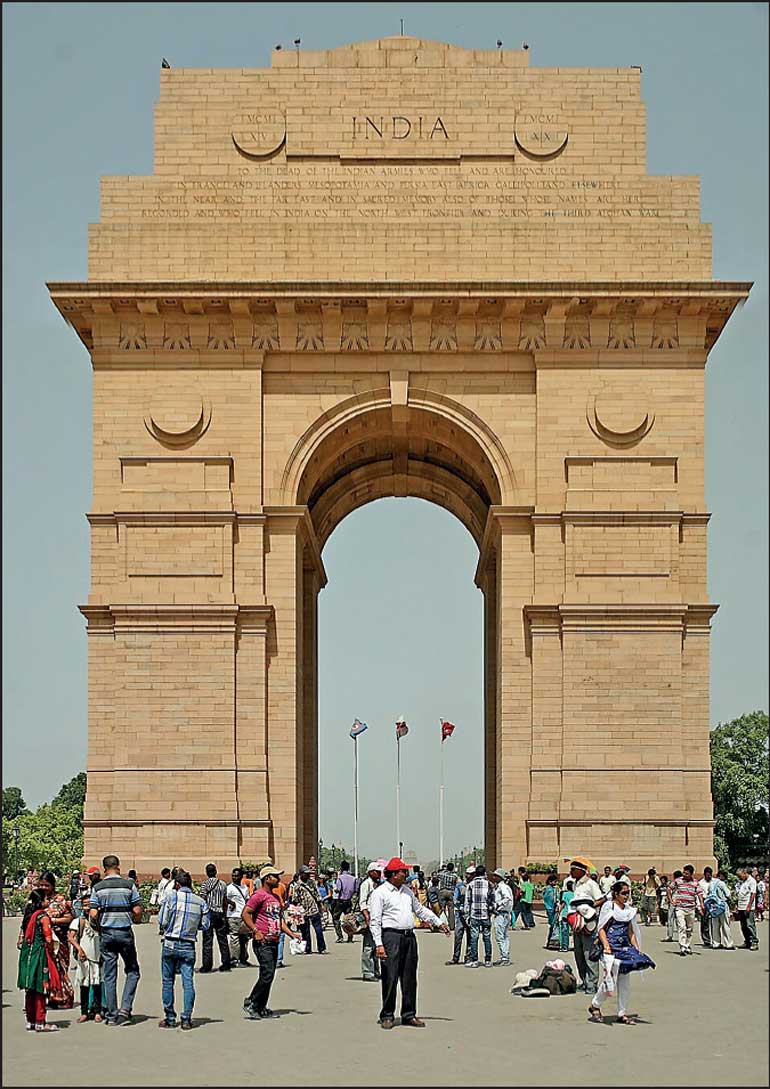

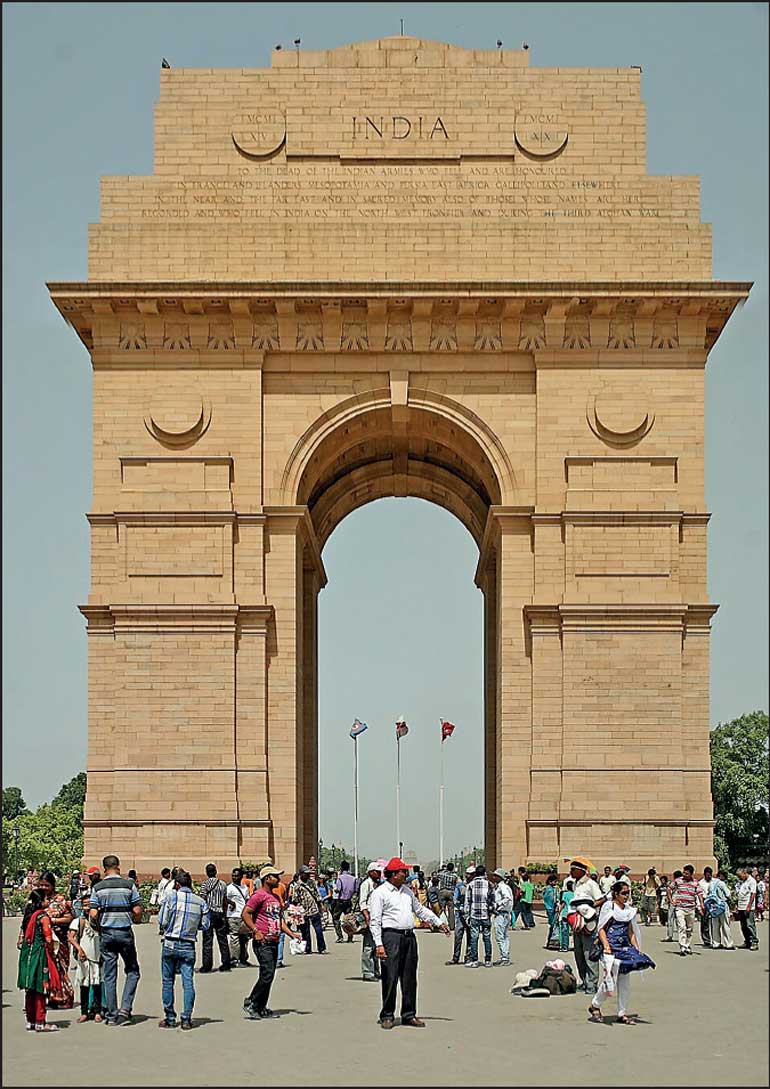

India overtakes Japan as world’s fourth-largest economy at $ 4.18 t

Thursday, 30 October 2025

The rise and fall of globalisation: why the world’s next financial meltdown could be much worse with the US on the sidelines

Steve Schifferes, City St George's, University of London

This is the second in a two-part series. Read part one here.

Globalisation has always had its critics – but until recently, they have come mainly from the left rather than the right.

In the wake of the second world war, as the world economy grew rapidly under US dominance, many on the left argued that the gains of globalisation were unequally distributed, increasing inequality in rich countries while forcing poorer countries to implement free-market policies such as opening up their financial markets, privatising their state industries and rejecting expansionary fiscal policies in favour of debt repayment – all of which mainly benefited US corporations and banks.

This was not a new concern. Back in 1841, German economist Friedrich List had argued that free trade was designed to keep Britain’s global dominance from being challenged, suggesting:

When anyone has obtained the summit of greatness, he kicks away the ladder by which he climbs up, in order to deprive others of the means of climbing up after him.

By the 1990s, critics of the US vision of a global world order such as the Nobel-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz argued that globalisation in its current form benefited the US at the expense of developing countries and workers – while author and activist Naomi Klein focused on the negative environmental and cultural consequences of the global expansion of multinational companies.

Mass left-led demonstrations broke out, disrupting global economic meetings including, most famously, the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1999. During this “battle of Seattle”, violent exchanges between protesters and police prevented the launch of a new world trade round that had been backed by then US president, Bill Clinton. For a while, the mass mobilisation of a coalition of trade unionists, environmentalists and anti-capitalist protesters seemed set to challenge the path towards further globalisation – with anti-capitalism “Occupy” protests spreading around the world in the wake of the 2008 financial crash.

A documentary about the 1999 ‘batte of Seattle’, directed by Jill Friedberg and Rick Rowley.

In the US, a further critique of globalisation centred on its domestic consequences for American workers – namely, job losses and lower pay – and led to calls for greater protectionism. Although initially led by trade unions and some Democratic politicians, this critique gradually gained purchase in radical right circles who opposed giving any role to international organisations like the WTO, on the grounds that they impinged on American sovereignty. According to this view, only by stopping foreign competition whose low wages undercut American workers could prosperity be restored. Immigration was another target.

Under Donald Trump’s second term as US president, these criticisms have been transformed into radical, deeply disruptive economic and social policies – with tariffs and protectionism at their heart. In so doing, Trump – despite all his grandstanding on the world stage – has confirmed what has long been clear to close observers of US politics and business: that the American century of global dominance, with the dollar as unrivalled no.1 currency, is drawing rapidly to a close.

Even before Trump first took office in 2017, the US had begun to withdraw from its leadership role in international economic institutions such as the WTO. Now, the strongest part of its economy, the hi-tech sector, is under intense pressure from China, whose economy is already bigger than the US’s by one key measure of GDP. Meanwhile, the majority of US citizens are facing stagnant incomes, higher prices and more insecure jobs.

In previous centuries, when first France and then Great Britain reached the end of their eras of world domination, these transitions had painful impacts beyond their borders. This time, with the global economy more closely integrated than ever before and no single dominant power waiting in the wings to take over, the impacts could be felt even more widely – with very damaging, if not catastrophic, results.

Why no one is ready to take the US’s place

When it comes to taking over from the US as the world’s leading hegemonic power, the only viable candidates with big enough economies are the European Union and China. But there are strong reasons to doubt that either could take on this role – notwithstanding the fact that in 2022, then US president Joe Biden’s National Security Strategy called China: “The only competitor with both the intent to reshape the international order and, increasingly, the economic, diplomatic, military and technological power to do so.”

At times Biden’s successor, President Trump, has sounded almost jealous of the control China’s leaders exert over their national economy, and the fact they do not face elections and limits on their terms in office. But a one-party, authoritarian political system which lacks legal checks and balances is a key reason China will find it hard to gain the cultural and political dominance among democratic nations that is part of achieving world no.1 status – despite the influence it already wields in large parts of Asia and Africa.

China still faces big economic challenges too. While it is already the global leader in manufactured goods (rapidly moving into hi-tech products) and the world’s largest exporter, its economy is still very unbalanced – with a much smaller consumer sector, a weak property market, many inefficient state industries that are highly indebted, and a relatively small financial sector restricted by state ownership. Nor does China possess a global currency, despite its (limited) attempts to make the renminbi a truly international currency.

The Insights section is committed to high-quality longform journalism. Our editors work with academics from many different backgrounds who are tackling a wide range of societal and scientific challenges.

As I found on a reporting trip to Shanghai in 2007 to investigate the effects of globalisation, there are also enormous differences between China’s prosperous coastal megacities – whose main thoroughfares rival New York and Paris – and the relative poverty in the interior, especially in rural areas. But nearly two decades on from that visit, with the country’s growth rate slowing, many university-educated young people are also finding it hard to find well-paid jobs now.

Meanwhile Europe – the only other contender to take the US’s place as global no.1 – is deeply politically divided, with smaller, weaker economies to the east and south far more sceptical about the benefits of globalisation, and increasingly divided on issues such as migration and the Ukraine war. The challenges of achieving broad policy agreement among all member states, and the problem of who can speak for Europe, make it unlikely that the EU as currently constituted could initiate and enforce a new global world order on its own.

The EU’s financial system also lacks the heft of the US’s. Although it has a common currency (the euro) managed by the European Central Bank, its financial system is far more fragmented. Banks are regulated nationally, and each country issues its own government bonds (although a few eurobonds now exist). This makes it hard for the euro to replace the dollar as a store of value, and reduces the incentive for foreigners to hold euros as an alternative reserve currency.

Meanwhile, any future prospects of a renewal of US global leadership look similarly unpromising. Trump’s policy of cutting taxes while increasing the size of the US government debt – which now stands at US$38 trillion, or 120% of GDP – threatens both the stability of the world economy and the ability of the US to finance this mind-boggling deficit.US national debt hits record high. Video: The Economic Times.

Our current, nameless global order, which is dominated by the WTO and is notionally designed to pursue economic efficiency and regulate the trade policies of its 166 member countries, is untenable and unsustainable. The US has paid for this system with the loss of industrial jobs and economic security, and the biggest winner has been China.

While the US is not, so far, withdrawing from the IMF, the Trump administration has urged it to call out China for running such a large trade surplus, while abandoning its concern about climate change. Greer concluded that the US has “subordinated our country’s economic and national security imperatives to a lowest common denominator of global consensus”.

World without a global no.1

To understand the potential dangers ahead, we must go back more than a century to the last time there was no global hegemon. By the time the first world war officially ended with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on June 28 1919, the international economic order had collapsed. Britain, world leader over the previous century, no longer possessed the economic, political or military clout to enforce its version of globalisation.

The UK government, burdened by the huge debts it had taken out to finance the war effort, was forced to make major cuts in public spending. In 1931, it faced a sterling crisis: the pound had to be devalued as the UK exited from the gold standard for good, despite having yielded to the demands of international bankers to cut payments to the unemployed. This was a final sign that Britain had lost its dominant place in the world economic order.

The 1930s were a time of deep political unease and unrest in Britain and many other countries. In 1936, unemployed workers from Jarrow, a town in north-east England with 70% unemployment after its shipyards closed, organised a non-political “hunger march” to London which became known as the Jarrow crusade. More than 200 men, dressed in their Sunday best, marched peacefully in step for over 200 miles, gaining great support along the way. Yet when they reached London, prime minister Stanley Baldwin ignored their petition – and the men were informed their dole money would be docked because they had been unavailable for work over the past fortnight.

The Jarrow marchers en route to London in October 1936. National Media Museum/Wikimedia

The Jarrow marchers en route to London in October 1936. National Media Museum/WikimediaEurope was also facing a severe economic crisis. After Germany’s government refused to pay the reparations agreed in the 1919 Versailles treaty, saying they would bankrupt its economy, the French army occupied the German industrial heartland of the Ruhr and German workers went on strike, supported by their government. The ensuing struggle fuelled hyperinflation in Germany. By November 1923, it took 200,000 million marks to buy a loaf of bread, and the savings and pensions of the German middle class were wiped out. That month, Adolf Hitler made his first attempt to seize power in the failed “Beer hall putsch” in Munich.

In contrast, across the Atlantic, the US was enjoying a period of postwar prosperity, with a booming stock market and explosive growth of new industries such as car manufacturing. But despite emerging as the world’s strongest economic power, having financed much of the Allied war effort, it was unwilling to grasp the reins of global economic leadership.

The Republican US Congress, having blocked President Woodrow Wilson’s plan for a League of Nations, instead embraced isolationism and washed its hands of Europe’s problems. The US refused to cancel or even reduce the war debts owed it by the Allied nations, who eventually repudiated their debts. In retaliation, the US Congress banned all American banks from lending money to these so-called allies.

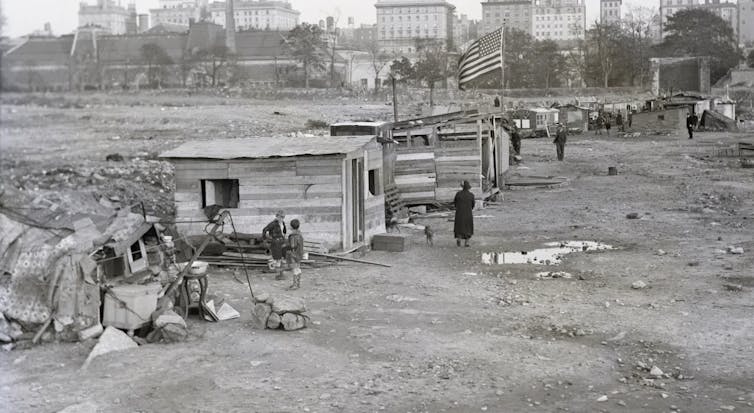

Then, in 1929, the affluent American “jazz age” came to an abrupt halt with a stock market crash that wiped off half its value. The country’s largest manufacturer, Ford, closed its doors for a year and laid off all its workers. With a quarter of the nation unemployed, long lines for soup kitchens were seen in every city, while those who had been evicted camped out wherever they could – including in New York’s Central Park, renamed “Hooverville” after the hapless US president of that time, Herbert Hoover.

Hooverville in New York’s Central Park during the Great Depression. Hmalcolm03/Wikimedia, CC BY-NC-ND

Hooverville in New York’s Central Park during the Great Depression. Hmalcolm03/Wikimedia, CC BY-NC-NDIn rural areas where the collapse in agricultural prices meant farmers could no longer make a living, armed farmers stopped food and milk trucks and destroyed their contents in a vain attempt to limit supply and raise prices. By March 1933, as President Franklin D. Roosevelt took office, the entire US banking system had ground to a standstill, with no one able to withdraw money from their bank account.

With its focus on this devastating Great Depression, the US refused to get involved in attempts at international economic cooperation. With no notice, Roosevelt withdrew from the 1933 London Conference which had been called to stabilise the world’s currencies – sending a message denouncing “the old fetishes of the so-called international bankers”.

With the US following the UK off the gold standard, the resulting currency wars exacerbated the crisis and further weakened European economies. As countries reverted to mercantilist policies of protectionism and trade wars, world trade shrank dramatically.

The situation became even worse in central Europe, where the collapse of the huge Credit-Anstalt bank in Austria in 1931 reverberated around the region. In Germany, as mass unemployment soared, centrist parties were squeezed and armed riots broke out between communist and fascist supporters. When the Nazis came to power, they introduced a policy of autarky, cutting economic ties with the west to build up their military machine.

The economic rivalries and antagonisms which weakened western economies paved the way for the rise of fascism in Germany. In some sense, Hitler – an admirer of the British empire – aspired to be the next hegemonic economic as well as military power, creating his own empire by conquering and ruthlessly exploiting the resources of the rest of Europe.

Troubled by rampant hyperinflation, Germans queue up with large bags to withdraw money from Berlin’s Reichsbank in 1923. Bundesarchiv/Wikimedia, CC BY-NC-SA

Troubled by rampant hyperinflation, Germans queue up with large bags to withdraw money from Berlin’s Reichsbank in 1923. Bundesarchiv/Wikimedia, CC BY-NC-SANearly a century later, there are some disturbing parallels with that interwar period. Like America after the first world war, Trump insists that countries the US has supported militarily now owe it money for this protection. He wants to encourage currency wars by devaluing the dollar, and raise protectionist barriers to protect domestic industry. The 1920s was also a time when the US sharply limited immigration on eugenic grounds, only allowing it from northern European countries which (the eugenicists argued) would not “pollute the white race”.

Clearly, Trump does not view the lack of international cooperation that could amplify the damaging economic effects of a stock or bond market crash as a problem that should concern him. And in today’s unstable world, for all the US’s past failings as a global leader, that is a very worrying proposition.

How the US responded to the last financial crisis

Once again, the rules of the international order are breaking down. While it is possible that Trump’s approach will not be fully adopted by his successor in the White House, the direction of travel in the US will almost certainly remain sceptical about the benefits of globalisation, with limited support for any worldwide economic rules or initiatives.

We see similar scepticism about the benefits of globalisation emerging in other countries, amid the rise of rightwing populist parties in much of Europe and South America – many backed by Trump. Fuelling these parties’ support are growing concerns about income inequality, slow growth and immigration which are not being addressed by the current political system – and all of which would be exacerbated by the onset of a new global economic crisis.

With the global economy and financial system far bigger than ever before, a new crisis could be even more severe than the one that occurred in 2008, when the failure of the banking system left the world teetering on the brink of collapse.

The scale of this crisis was unprecedented, but key US and UK government officials moved boldly and swiftly. As a BBC reporter in Washington, I attended the House of Representatives’ Financial Services Committee hearing three days after Lehman Brothers went bankrupt, paralysing the global financial system, to find out the administration’s response. I remember the stunned look on the face of the committee’s chairman, Barney Frank, when he asked US Treasury secretary Hank Paulson and US Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke how much money they might need to stabilise the situation:

“Let’s start with US$1 trillion,” Bernanke replied coolly. “But we have another US$2 trillion on our balance sheet if we need it.”

Documentary on the collapse of Lehman Brothers bank in September 2008.

Shortly afterwards, the US Congress approved a US$700 billion rescue package. While the global economy has still not fully recovered from this crisis, it could have been far worse – possibly as bad as the 1930s – without such intervention.

Around the world, governments ended up pledging US$11 trillion to guarantee the solvency of their banking systems, with the UK government putting up a sum equivalent to the country’s entire yearly GDP. But it was not just governments. At the G20 summit in London in April 2009, a new US$1.1 trillion fund was set up by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to advance money to countries that were getting into financial difficulty.

The G20 also agreed to impose tougher regulatory standards for banks and other financial institutions that would apply globally, to replace the weak regulation of banks that had been one of the main causes of the crisis. As a reporter at this summit, I recall widespread excitement and optimism that the world was finally working together to tackle its global problems, with the host prime minister, Gordon Brown, briefly glowing in the limelight as organiser of that summit.

Behind the scenes, the US Federal Reserve had also been working to contain the crisis by quietly passing on to the world’s other leading central banks nearly US$600 billion in “currency swaps” to ensure they had the dollars they needed to bail out their own banking systems. The Bank of England secretly lent UK banks £100 billion to ensure they didn’t collapse, although two of the four major banks, Royal Bank of Scotland (now NatWest) and Lloyds, ultimately had to be nationalised (to different extents) to keep the financial system stable.

However, these rescue packages for banks, while much needed to stabilise the global economy, did not extend to many of the victims of the crash – such as the 12 million US households whose homes were now worth less than the mortgage they had taken out to pay for them, or the 40% of households who experienced financial distress during the 18 months after the crash. And the ramifications of the crisis were even greater for those living in developing countries.

A few months after the 2008 financial crisis began, I travelled to Zambia, an African country totally dependent on copper exports for its foreign exchange. I visited the Luanshya copper mine near Ndola in the country’s copper belt. With demand for copper (used mainly in construction and car manufacturing) collapsing, all the copper mines had closed. Their workers, in one of the few well-paid jobs in Zambia, were forced to leave their comfortable company homes and return to sharing with their relatives in Lusaka without pay.

Zambia’s government was forced to shut down its planned poverty reduction plan, which was to be funded by mining profits. The collapse in exports also damaged the Zambian currency, which dropped sharply. This hit the country’s poorest people hard as it raised the price of food, most of which was imported.

The ripple effects of the 2008 global financial crisis soon hit Luanshya copper mine in Zambia. Nerin Engineering Co., CC BY-SA

The ripple effects of the 2008 global financial crisis soon hit Luanshya copper mine in Zambia. Nerin Engineering Co., CC BY-SAI also visited a flower farm near Lusaka, where Dutch expats Angelique and Watze Elsinga had been growing roses for export for over a decade – employing more than 200 workers who were given housing and education. As the market for Valentine’s Day roses collapsed, their bankers, Barclays South Africa, suddenly ordered them to immediately repay all their loans, forcing them to sell their farm and dismiss their workers. Ultimately, it took a US$3.9 billion loan from the IMF and World Bank to stabilise Zambia’s economy.

Should another global financial crisis hit, it is hard to see the Trump administration (and others that follow) being as sympathetic to the plight of developing countries, or allowing the Federal Reserve to lend major sums to foreign central banks – unless it is a country politically aligned with Trump, such as Argentina. Least likely of all is the idea of Trump working with other countries to develop a global trillion-dollar rescue package to help save the world economy.

Rather, there is a real worry that reckless actions by the Trump administration – and weak global regulation of financial markets – could trigger the next global financial crisis.

What happens if the US bond market collapses?

Economic historians agree that financial crises are endemic in the history of global capitalism, and they have been increasing in frequency since the “hyper-globalisation” of the 1970s. From Latin America’s debt crisis in the 1980s to the Asia currency crisis in the late 1990s and the US dotcom stock market collapse in the early 2000s, crises have regularly devastated economies and regions around the world.

Today, the greatest risk is the collapse of the US Treasury bond market, which underpins the global financial system and is involved in 70% of global financial transactions by banks and other financial institutions. Around the world, these institutions have long regarded the US bond market, worth over $30 trillion, as a safe haven, because these “debt securities” are backed by the US central bank, the Federal Reserve.

Increasingly, the unregulated “shadow banking system” – a sector now larger than regulated global banks – is deeply involved in the bond market. Non-bank financial institutions such as private equity, hedge funds, venture capital and pension funds are largely unregulated and, unlike banks, are not required to hold reserves.

Bond market jitters are already unnerving global financial markets, which fear its unravelling could precipitate a banking crisis on the scale of 2008 – with highly leveraged transactions by these non-bank financial institutions leaving them exposed.US bonds play a key role in maintaining the stability of the global economy. Video: Wall Street Journal.

Buyers of US bonds are also troubled by the Trump administration’s plan to raise the US deficit even higher to pay for tax cuts – with the national debt now forecast to rise to 134% of US GDP by 2035, up from 120% in 2025. Should this lead to a widespread refusal to buy more US bonds among jittery investors, their value would collapse and interest rates – both in the US and globally – would soar.

The governor of the Bank of England, Andrew Bailey, recently warned that the situation has “worrying echoes of the 2008 financial crisis”, while the head of the IMF, Kristalina Georgieva, said her worries about the collapse of private credit markets sometimes keep her awake at night.

A bad situation would grow even worse if problems in the bond market precipitate a sharp decline in the value of the dollar. The world’s “anchor currency” would no longer be seen as a safe store of value – leading to more withdrawals of funds from the US Treasury bond market, where many foreign governments hold their reserves.

A weaker dollar would also hit US exporters and multinational companies by making their goods more expensive. Yet extraordinarily, this is precisely the course advocated by Stephen Miran, chair of the US president’s Council of Economic Advisors – who Trump appears to want to be the next head of the Federal Reserve.

One example of what could happen if bond markets become destabilised occurred when the shortest-lived prime minister in UK history, Liz Truss, announced huge unfunded tax cuts in her 2022 budget, causing the value of UK gilts (the equivalent of US Treasury bonds) to plummet as interest rates spiked. Within days, the Bank of England was forced to put up an emergency £60 billion rescue fund to avoid major UK pension funds collapsing.

In the case of a US bond market crash, however, there are growing fears that the US government would be unable – and unwilling – to step in to mitigate such damage.

A new era of financial chaos

Just as worrying would be a crash of the US stock market – which, by historic standards, is currently vastly overvalued.

Huge recent increases in the US stock market’s overall value have been driven almost entirely by the “magnificent seven” hi-tech companies, which alone make up a third of its total value. If their big bet on artificial intelligence is not as lucrative as they claim, or is overshadowed by the success of China’s AI systems, a sharp downturn, similar to the dotcom crash of 2000-02, could well occur.

Jamie Dimon, head of the US’s biggest bank JPMorgan Chase, has said he is “far more worried than other [experts]” about a serious market correction, which he warned could come in the next six months to two years.

Big tech executives have been overoptimistic before. Reporting from Silicon Valley in 2001 as the dotcom bubble was bursting, I was struck by the unshakeable belief of internet startup CEOs that their share prices could only go up.

Furthermore, their companies’ high stock valuations had allowed them to take over their competitors, thus limiting competition – just as companies such as Google and Meta (Facebook) have since used their highly valued shares to purchase key assets and potential rivals including YouTube, WhatsApp, Instagram and DeepMind. History suggests this is always bad for the economy in the long run.

With the business and financial worlds now ever more closely linked, not only has the frequency of financial crises increased in the last half-century, each crisis has become more interconnected. The 2008 global financial crisis showed how dangerous this can be: a global banking crisis triggered stock market falls, collapses in the value of weak currencies, a debt crisis in developing countries – and ultimately, a global recession that has taken years to recover from.

The IMF’s latest financial stability report summarised the situation in worrying terms, highlighting “elevated” stability risks as a result of “stretched asset valuations, growing pressure in sovereign bond markets, and the increasing role of non-bank financial institutions. Despite its deep liquidity, the global foreign exchange market remains vulnerable to macrofinancial uncertainty.”The IMF has warned about instability in the global financial system. Video: CGTN America.

I believe we may be entering a new era of sustained financial chaos during which the seeds sown by the death of globalisation – and Trump’s response to it – finally shatter the world economic and political order established after the second world war.

Trump’s high and erratically applied tariffs – aimed most strongly at China – have already made it difficult to reconfigure global supply chains. Even more worrying could be the struggle over the control of key strategic raw materials like the rare earth minerals needed for hi-tech industries, with China banning their export and the US threatening 100% tariffs in return (as well as hoping to take over Greenland, with its as-yet-untapped supply of some of these minerals).

This conflict over rare earths, vital for the computer chips needed for AI, could also threaten the market value of high-flying tech stocks such as Nvidia, the first company to exceed US$4 trillion in value.

The battle for control of critical raw materials could escalate. There is a danger that in some cases, trade wars might become real wars – just as they did in the former era of mercantilism. Many recent and current regional conflicts, from the first Iraq war aimed at the conquest of the oilfields of Kuwait, to the civil war in Sudan over control of the country’s goldmines, are rooted in economic conflicts.

The history of globalisation over the past four centuries suggests that the presence of a global superpower – for all its negative sides – has brought a degree of economic stability in an uncertain world.

In contrast, a key lesson of history is that a return to policies of mercantilism – with countries struggling to seize key natural resources for themselves and deny them to their rivals – is most likely a recipe for perpetual conflict. But this time around, in a world full of 10,000 nuclear weapons, miscalculations could be fatal if trust and certainty are undermined.

The challenges ahead are immense – and the weakness of international institutions, the limited visions of most governments and the alienation of many of their citizens are not optimistic signs.

This is the second in a two-part series. In case you missed it, read part one here.

For you: more from our Insights series:

Could digital currencies end banking as we know it? The future of money

Welcome to post-growth Europe – can anyone accept this new political reality?

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.![]()

Steve Schifferes, Honorary Research Fellow, City Political Economy Research Centre, City St George's, University of London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Sunday, 19 October 2025

US economy is already on the edge – a prolonged government shutdown could send it tumbling over

John W. Diamond, Rice University

The economic consequences of the current federal government shutdown hinge critically on how long it lasts. If it is resolved quickly, the costs will be small, but if it drags on, it could send the U.S. economy into a tailspin.

That’s because the economy is already in a precarious state, with the labor market struggling, consumers losing confidence and uncertainty mounting.

As an economist who studies public finance, I closely follow how government policies affect the economy. Let me explain how a prolonged shutdown could affect the economy – and why it could be a tipping point to recession.

Direct impacts from a government shutdown

The partial government shutdown began on Oct. 1, 2025, as Democrats and Republicans failed to reach a deal on funding some portion of the federal government. A partial shutdown means that some funding bills have been approved, entitlement spending continues since it does not rely on annual appropriations, and some workers are deemed necessary and stay on the job unpaid.

While most of the 20 shutdowns that occurred from 1976 through 2024 lasted only a few days to a week, there are signs the current one may not be resolved so quickly. The economy would definitely take a direct hit to gross domestic product from a lengthy shutdown, but it’s the indirect impacts that could be more harmful.

The most recent shutdown, which extended over the 2018-2019 winter holidays and lasted 35 days, was the longest in U.S. history. After it ended, the Congressional Budget Office estimated the partial shutdown delayed approximately US$18 billion in federal discretionary spending, which translated into an $11 billion reduction in real GDP.

Most of that lost output was made up later once the shutdown ended, the CBO noted. It estimated that the permanent losses were about $3 billion – a drop in the bucket for the $30 trillion U.S. economy.

The indirect and more lasting impacts

The full impact may depend to a large extent on the psychology of the average consumer.

Recent data suggests that consumer confidence is falling as the stagnation in the labor market becomes more clear. Business confidence has been mixed as the manufacturing index continues to indicate the sector is in contraction, while other business confidence measures indicate mixed expectations about the future.

If the shutdown drags on, the psychological effects may lead to a larger loss of confidence among consumers and businesses. Given that consumer spending accounts for 70% of economic activity, a fall in consumer confidence could signal a turning point in the economy.

These indirect effects are in addition to the direct impact of lost income for federal workers and those that operate on federal contracts, which leads to reductions in consumption and production.

The risk of significant government layoffs, beyond the usual furloughs, could deepen the economic damage. Extensive layoffs would shift the losses from a temporary delay to a more permanent loss of income and human capital, reducing aggregate demand and potentially increasing unemployment spillovers into the private sector.

In short, while shutdowns that end quickly tend to inflict modest, mostly recoverable losses, a protracted shutdown – especially one involving layoffs of a significant number of government workers – could inflict larger, lasting impacts on the economy.

US economy is already in distress

This is all occurring as the U.S. labor market is flashing warnings.

Payrolls grew by only 22,000 in August, with July and June estimates revised down by 21,000. This follows payroll growth of only 73,000 in July, with May and June estimates revised down by 258,000. In addition, preliminary annual revisions to the employment data show the economy gained 911,000 fewer jobs in the previous year than had been reported.

Long-term unemployment is also rising, with 1.8 million people out of work for more than 27 weeks – nearly a quarter of the total number of unemployed individuals.

At the same time, AI adoption and cost-cutting could further reduce labor demand, while an aging workforce and lower immigration shrink labor supply. Fed Chair Jerome Powell refers to this as a “curious kind of balance” in the labor market.

In other words, the job market appears to have come to a screeching halt, making it difficult for recent graduates to find work. Recent graduate unemployment – that is, those who are 22 to 27 years old – is now 5.3% relative to the total unemployment rate of 4.3%.

The latest data from the ADP employment report, which measures only private company data, shows that the economy lost 32,000 jobs in September. That’s the biggest decline in 2½ years. While that’s worrying, economists like me usually wait for the official Bureau of Labor Statistics numbers to come out to confirm the accuracy of the payroll processing firm’s report.

The government data that was supposed to come out on Oct. 3 might have offered a possible counterpoint to the bad ADP news, but due to the shutdown BLS will not be releasing the report.

Problems Fed rate cuts can’t fix

This will only increase the uncertainty surrounding the health of the U.S. economy. And it adds to the uncertainty created by on-again, off-again tariffs as well as the newly imposed tariffs on lumber, furniture and other goods.

Against this backdrop, the Fed is expected to lower interest rates at least two more times this year to stimulate consumer and business spending following its September quarter-point cut. This raises the risk of reigniting inflation, but the cooling labor market is a more immediate concern for the Fed.

While lower short-term rates may help at the margin, I believe they cannot resolve the deeper challenges, such as massive government deficits and debt, tight household budgets, a housing affordability crisis and a shrinking labor force.

The question now is not will the Fed cut rates, because it likely will, but whether that cut will help, particularly if the shutdown lasts weeks or more. Monetary policy alone cannot overcome the uncertainty created by tariffs, the lack of fiscal restraint, companies focused on cutting costs by replacing people with technology, the impact of the shutdown and the fears of consumers about the future.

Lower interest rates may buy time, but they won’t solve these structural problems facing the U.S. economy.![]()

John W. Diamond, Director of the Center for Public Finance at the Baker Institute, Rice University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Wednesday, 4 June 2025

A free clinic for donkeys, vital to Ethiopia's economy

Monday, 10 February 2025

World Bank cuts 2025 growth forecasts for 70% of economies

Tuesday, 28 January 2025

AI can add $4.4 trillion to global economy, but digital divide must be removed: WEF report

Friday, 17 January 2025

World Bank looks to fresh beginning in Sri Lanka

Tuesday, 3 September 2024

India achieves 40th rank in 2023 edition of Global Innovation Index

Wednesday, 26 June 2024

World Bank says 80% of global population will experience slower growth than in pre-COVID decade

- Latest Global Economic Prospects report acknowledges global growth stabilising for first time in three years

- The global economy is expected to stabilise for the first time in three years in 2024—but at a level that is weak by recent historical standards, according to the World Bank’s latest Global Economic Prospects report released on Thursday.

- Global growth is projected to hold steady at 2.6% in 2024 before edging up to an average of 2.7% in 2025-26. That is well below the 3.1% average in the decade before COVID-19. The forecast implies that over the course of 2024-26 countries that collectively account for more than 80% of the world’s population and global GDP would still be growing more slowly than they did in the decade before COVID-19.

- Overall, developing economies are projected to grow 4% on average over 2024-25, slightly slower than in 2023. Growth in low-income economies is expected to accelerate to 5% in 2024 from 3.8% in 2023. However, the forecasts for 2024 growth reflect downgrades in three out of every four low-income economies since January. In advanced economies, growth is set to remain steady at 1.5% in 2024 before rising to 1.7% in 2025.

- “Four years after the upheavals caused by the pandemic, conflicts, inflation, and monetary tightening, it appears that global economic growth is steadying,” said World Bank Group’s Chief Economist and Senior Vice President Indermit Gill. “However, growth is at lower levels than before 2020. Prospects for the world’s poorest economies are even more worrisome. They face punishing levels of debt service, constricting trade possibilities, and costly climate events. Developing economies will have to find ways to encourage private investment, reduce public debt, and improve education, health, and basic infrastructure. The poorest among them—especially the 75 countries eligible for concessional assistance from the International Development Association—will not be able to do this without international support.”

- This year, one in four developing economies is expected to remain poorer than it was on the eve of the pandemic in 2019. This proportion is twice as high for countries in fragile- and conflict-affected situations. Moreover, the income gap between developing economies and advanced economies is set to widen in nearly half of developing economies over 2020-24—the highest share since the 1990s. Per capita income in these economies—an important indicator of living standards—is expected to grow by 3.0% on average through 2026, well below the average of 3.8% in the decade before COVID-19.

- Global inflation is expected to moderate to 3.5% in 2024 and 2.9% in 2025, but the pace of decline is slower than was projected just six months ago. Many central banks, as a result, are expected to remain cautious in lowering policy interest rates. Global interest rates are likely to remain high by the standards of recent decades—averaging about 4% over 2025-26, roughly double the 2000-19 average.

- “Although food and energy prices have moderated across the world, core inflation remains relatively high—and could stay that way,” said World Bank’s Deputy Chief Economist and Prospects Group Director Ayhan Kose. “That could prompt central banks in major advanced economies to delay interest-rate cuts. An environment of ‘higher-for-longer’ rates would mean tighter global financial conditions and much weaker growth in developing economies.”

- The latest Global Economic Prospects report also features two analytical chapters of topical importance. The first outlines how public investment can be used to accelerate private investment and promote economic growth. It finds that public investment growth in developing economies has halved since the global financial crisis, dropping to an annual average of 5% in the past decade. Yet public investment can be a powerful policy lever. For developing economies with ample fiscal space and efficient government spending practices, scaling up public investment by 1% of GDP can increase the level of output by up to 1.6% over the medium term.

- The second analytical chapter explores why small states—those with a population of around 1.5 million or less—suffer chronic fiscal difficulties. Two-fifths of the 35 developing economies that are small states are at high risk of debt distress or already in it. That’s roughly twice the share for other developing economies. Comprehensive reforms are needed to address the fiscal challenges of small states. Revenues could be drawn from a more stable and secure tax base. Spending efficiency could be improved—especially in health, education, and infrastructure. Fiscal frameworks could be adopted to manage the higher frequency of natural disasters and other shocks. Targeted and coordinated global policies can also help put these countries on a more sustainable fiscal path.World Bank says 80% of global population will experience slower growth than in pre-COVID decade | Daily FT

Tuesday, 21 May 2024

What’s the difference between fiscal and monetary policy?

This article is part two of The Conversation’s “Business Basics” series where we ask leading experts to discuss key concepts in business, economics and finance.

How governments should manage their budgets, and how interest rates should be set, are two of the most important questions in economics.

Ideally, both work hand in hand to ensure the best outcomes for the economy as a whole. But they are enacted by different branches of government, and fall into different buckets within economics.

Budgeting – the way governments tax and spend – falls within the domain of fiscal policy. In contrast, the management of credit and interest rates falls into the domain of monetary policy.

With the recent federal budget handed down amid an ongoing battle to tackle inflation, both topics have dominated recent news coverage, so it’s important to understand the difference.

Fiscal policy

Paying tax is an unavoidable fact of life, but is needed to support spending on government services such as hospitals, roads, schools and defence. Taxation and spending decisions are made on different scales at every level of government, and form the basis of a government’s fiscal policy.

Traditionally, fiscal policy was seen as a very simple equation.

Governments should spend only as much as they earn through taxation, and only take on a small amount of debt for things like longer-term infrastructure projects.

But when economic growth falls, tax revenues also fall, forcing governments to cut spending to balance their budgets. Such spending cuts come at precisely the wrong time and are only likely to further worsen economic growth.

Noticing this pattern, economist John Maynard Keynes was the first to question this traditional wisdom, arguing that fiscal policy should be “countercyclical”.

According to Keynes, when economic growth falls, government spending should increase, only falling back as the economic recovery plays out.

Under a Keynesian approach, it’s therefore wholly appropriate for governments to issue debt to fund spending increases as the economy weakens.

The problem with this view of fiscal policy is that some governments have arguably abused their licence to spend, relying on ever-increasing levels of debt.

Greece famously suffered a spectacular debt crisis after the global financial crisis in 2008, but other European countries such as France, Italy, Portugal and Spain also have high and problematic levels of debt.

Chronically high debt can lead to higher interest payments on this debt, which in turn can limit a government’s ability to spend to support its economy.

Monetary policy

By changing the relative cost of borrowing money, changes in interest rates affect the aggregate level of spending in the economy.

This in turn can impact inflation – increases in the general level of prices.

Cuts in interest rates will tend to stimulate demand and push prices up, while rate increases reduce demand and push prices down.

Interest rates are typically set by a country’s central bank, whose primary role is to keep inflation low.

Our own central bank – the Reserve Bank of Australia, sets rates to meet an official inflation target of between 2% and 3%.

A combined Keynesian approach

Alongside Keynes’ writing on fiscal policy, he and other economists argued that interest rates should be reduced as an economy heads into recession, to support borrowing and spending by businesses and consumers.

Coupled with higher government spending, keeping interest rates lower in a recession should theoretically speed up economic recovery.

The merits of a Keynesian approach were borne out clearly in Australia in both the 2008 global financial crisis and the COVID pandemic.

Most recently, the pandemic saw the Reserve Bank cut interest rates to almost zero. Simultaneously, the government supported the economy with a wide range of spending programs, including big boosts to welfare payments and a generous JobKeeper program to mothball Australia’s workforce.

As a result, unemployment quickly returned to low levels and economic growth recovered following the lifting of restrictions.

Helping people pay their bills while taming spending is hard

Emergence from the pandemic left us with a different problem. Inflation surged and remained stubbornly above the Reserve Bank’s target range, forcing the bank to repeatedly raise rates to try to tame it.

At the same time, the government has been trying to support Australians through a cost-of-living crisis.

Now, critics of the government have argued that further spending to support Australians could unintentionally put further pressure on inflation and force the Reserve Bank to keep interest rates higher for longer.

Such challenges reflect the fact that our understanding of best practice for fiscal and monetary policy is constantly evolving.

Problems with burgeoning state debt have prompted debate on the former, and whether there should be limits on governments’ ability to issue debt.

These could include limits to public debt, or new oversight authorities to monitor levels of public spending.

And on monetary policy, a recent review of the Reserve Bank considered requiring a “dual mandate” that would force it to give equal consideration to employment and to inflation goals, as is currently required of the US Federal Reserve.![]()

Mark Crosby, Professor, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Friday, 5 April 2024

World Bank projects India’s economy to grow at 7.5 per cent in 2024

Tuesday, 26 March 2024

French reactor using full core of recycled uranium fuel

.jpg?ext=.jpg) The Cruas-Meysse plant (Image: EDF)

The Cruas-Meysse plant (Image: EDF)