Monday, 5 January 2026

'It Feels Like Me Again': World’s First Arm Exoskeleton Gives Stroke Patients Independence

Monday, 10 November 2025

Driverless Electric Bus Eases Driver Shortages and Congestion In Madrid During Maiden Service

Tuesday, 7 October 2025

'Innovation in existing plants can help meet growth targets'

_65082.jpg)

Wednesday, 17 September 2025

This Undersea Tunnel Marvel is Set to Break 5 Records and Shave Hours Off Travel Times in Europe

The Fehmarnbelt tunnel will carry two rail lines and a pair of two-lane highways under the Baltic Sea – credit: Femern A/S, screenshot

The Fehmarnbelt tunnel will carry two rail lines and a pair of two-lane highways under the Baltic Sea – credit: Femern A/S, screenshot The tunnel elements will be floated into position – credit: Femern A/S, screenshot

The tunnel elements will be floated into position – credit: Femern A/S, screenshot A rendering showing the tunnel’s construction site and eventual opening – credit: Femern A/S, screenshot

A rendering showing the tunnel’s construction site and eventual opening – credit: Femern A/S, screenshotTuesday, 26 August 2025

Wildfires in Spain signal growing climate risks for Europe, expert warns

Wednesday, 11 June 2025

Renewable energy: rural areas can be the EU’s green powerhouse

Lewis Dijkstra, Joint Research Centre (JRC)

The European Union aims to cut greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% in 2030 compared to 1990 levels, and to become the first carbon-neutral economy by 2050. This ambitious goal requires a radical increase in the production of green energy within a relatively short timeframe. The untapped potential of rural areas in the union offers a way forward.

Rural areas could produce more energy than we need

Rural areas cover more than 80% of the EU’s territory and are host to around 30% of its population. Our work at the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC) shows that rural territories already generate the largest share of green electricity (72%) from the three most prominent renewable technologies: solar photovoltaic, onshore wind and hydropower. The remaining share of renewable energy is produced in towns and suburbs (22%) and cities (6%). Germany, Spain, France, Italy and Sweden are the top five renewable energy producers in the union, accounting for 68% of its total production from solar, onshore wind and hydropower installations.

But there is more. According to our analyses, rural areas also possess the highest untapped potential of renewable energy production–nearly 80%. Theoretically, they could produce enough to meet the total energy demand of the EU. We estimate that the total potential of solar, onshore wind and hydropower energy production in rural areas nears 12,500 terawatt hours per year. That’s more than five times the amount of electricity the union consumed in 2023, and it surpasses total energy consumption (which includes sources such as gas, oil and coal) for that year, too.

Technologies that suit the land

All this energy could be produced in rural areas without disrupting existing agricultural systems, landscapes and natural resources. Rural areas could produce up to 60 times more solar energy than what they currently deliver, quadruple their output from wind, and boost hydropower production by 25%. Spain, Romania, France, Portugal and Italy are the five EU countries with the highest combined (solar, wind and hydropower) untapped potential: together, they account for 67% of the EU’s potential, with contributions from rural areas ranging from 92% in France to 49% in Italy.

Overall, solar panels installed on the ground can make the biggest contribution to green energy production in the EU. However, rural areas across the union are highly diverse, so choosing the right technology would depend on local characteristics. Mountainous areas with abundant water resources are a good fit for hydropower production, while rural municipalities with large areas of suitable land lend themselves to solar or wind energy, depending on sun irradiation and wind speed. In rural areas where wind and land are insufficient, rooftop photovoltaic systems are a good option.

Boosting clean energy production can be a win-win

Rural areas are key to producing more renewable energy, as almost 80% of suitable, available land is located there. In addition, some of these areas are facing demographic and economic decline and are already the target of measures aimed at making them stronger, resilient and prosperous–as part of the EU’s long-term vision for rural areas. In this context, ensuring that these areas benefit economically from hosting more renewable energy projects makes them even more enticing. It also aligns with political considerations, as energy independence is a key part of the EU’s goal of strategic autonomy.

Addressing local concerns and fostering acceptance

While the potential offered by renewables is unquestionable, their production sites can face resistance from communities concerned about impacts on the local economy and quality of life. Seeing land used to produce energy with little local employment and seemingly for the benefit of large companies can also lead to resistance. Other concerns include competition for land use in areas where income is tied to other industries (such as agriculture or tourism), and the potential environmental impact of solar panels and wind or hydropower plants on rustic landscapes. With these concerns in mind, we identified portions of land suitable to host renewable energy plants that comprise roughly 3.4% of the EU’s surface. We excluded protected nature sites and biodiversity areas, forests and water bodies. We used strict limits on the use of agricultural land for energy production by only considering land that has been abandoned or has a very low productivity. Finally, we created buffer zones around infrastructure and settlements to minimise disturbance and safeguard natural beauty and cultural heritage.

Engaging local communities to find solutions

In our report, several case studies show the successful implementation of renewable energy projects in rural areas, driven by community engagement, collaboration and innovative financing models. From the first community-owned turbine in southern Europe in Catalonia, Spain, to a commercial energy company giving part of its profits to a local cause chosen with an energy community in the northern Netherlands, these cases highlight the potential for such projects to contribute to energy security, produce economic and social benefits and promote environmental sustainability.

These case studies show that active involvement of local communities from the early stages of renewable energy projects can foster acceptance. Citizens who are actively engaged or even share ownership in small- or medium-scale projects become more supportive. Beyond seeing profits stay local, engaged communities can mitigate negative effects of production by, for instance, choosing where to locate new energy plants.

Our report also offers an overview of renewable energy communities’ role in ensuring a sustainable energy transition in which rural areas are not left behind. The number of renewable energy communities in the EU is rising and, although an exact count is unavailable, it is estimated that there were over 4,000 of them, with some 900,000 members, in 2023. These communities are mainly concentrated in northwest Europe, and a high proportion are rural. Beyond energy communities, place-based approaches, where local populations and administrations are engaged from the early stages and see clear benefits, can make an important contribution to our sustainable transition.![]()

Lewis Dijkstra, Team Leader Urban and Territorial Analysis, Joint Research Centre (JRC)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tuesday, 18 March 2025

EU funding for French enrichment plant expansion

_20628.jpg)

Monday, 10 March 2025

Priceless ninth-century masterpiece Bible returns to Swiss homeland

Wednesday, 26 February 2025

AI regulation around the world

Tuesday, 12 November 2024

Belgians Grow Heaviest Pumpkin in Europe–Weighing as Much as a Honda Civic

Thursday, 5 September 2024

If Australia wants to fast-track 100% renewables, it must learn from Europe’s risky path

Even after decades encouraging the growth of renewables, we’re still too reliant on coal and gas power stations.

The problem isn’t in our ability to generate clean power. It’s what happens after that. Major roadblocks include the need for 10,000 kilometres of new transmission lines to connect rural renewable farms with city consumers. Another oft-cited reason is the need to store power from renewables so it can be drawn on as needed. This is why the Australian Energy Market Operator sees such a big role for large-scale storage coupled with some flexible gas as a backup.

Last year, renewable investment actually shrank in Australia. Reasons for the slowdown are wide-ranging. Some are local, such as rural communities lobbying against new transmission lines, the need for planning and environmental approvals and the slow pace of creating new regulations. Others are global, such as increased competition for engineers and electricians, clean tech and raw materials.

As climate change worsens, frustration about the slow pace of change will intensify. But when we look around the world, we see similar challenges cropping up in many countries.

European Union

Transmission line hold-ups are by no means a delay unique to Australia. Data from the International Energy Agency shows building new electricity grid assets takes ten years on average in both Europe and the United States.

In 2022, the European Union introduced laws expressly aimed at speeding up the clean energy transition by fast-tracking permits for renewables, grid investment and storage assets. These investments, the laws state, are:

presumed as being in the overriding public interest […] when balancing legal interests in the individual case.

That is, when the interests of other stakeholders – including local communities and the environment – clash with clean energy plans, clean energy has priority.

Germany has gone further still with domestic laws designed to further streamline planning and approvals and favour energy transition projects over competing interests. These changes were sweetened with financial incentives for communities participating in clean energy projects.

This is a risky path. European leaders have chosen to go faster in weaning off fossil fuels at the risk of inflaming local communities. The size of the backlash became clear in the EU’s elections in June, where populists gained seats and environmental parties lost.

United States

In 2022, the US government passed a huge piece of green legislation known as the Inflation Reduction Act. Rather than introducing further regulations, the US has gone for a green stimulus, offering A$600 billion in grants and tax credits for companies investing in green manufacturing, electric vehicles, storage and so on. To date, this approach has been very effective. But money isn’t everything – new transmission lines will be essential, which means approvals, planning, securing the land corridor and so on.

This year, the US Energy Department released new rules bundling all federal approvals into one program in a bid to accelerate the building of transmission lines across state borders.

Australia could borrow from this. The government’s Future Made in Australia policy package takes its cues from US green stimulus, but at smaller scale. What America’s example shows us is these incentives work – especially when big.

US-style streamlining and bundling of approvals could address delays from overlapping state and federal approvals. Supporting local green manufacturing can create jobs, which in turn encourages community buy-in.

China

Even as Australia’s clean energy push hit the doldrums and emission levels stagnated, China’s staggering clean energy push began bearing fruit. Emissions in the world’s largest emitter began to fall, five years ahead of the government’s own target.

They did this by covering deserts with solar panels, building enormous offshore wind farms, rolling out fast rail, building hydroelectricity, and taking up electric vehicles very rapidly. In 2012, China had 3.4 gigawatts of solar and 61 GW of wind capacity. In 2023, it had 610 GW of solar and 441 GW of wind. It’s also cornered the market in renewable technologies and moving strongly into electric vehicles.

Of course, China’s government has far fewer checks and balances and exerts tight control over communities and media. We don’t often see what costs are paid by communities.

China has also used industrial policy cleverly, with government and industries acting in partnership. In fact, the green push in the US, EU, Australia and other Western jurisdictions takes cues from China’s approach.

There’s still a long road ahead for China. But given its reliance on energy-intensive manufacturing, it’s remarkable China’s leaders have managed to halt the constant increase in emissions.

These examples show how it is possible to accelerate the energy transition. But often, it comes at a cost.

Costs can be monetary, such as when governments direct funding to green stimulus over other areas. But it can also be social, if the transition comes at the cost of community support or the health of the local environment.

This comes with the territory. Big infrastructure projects benefit many but disadvantage some.

While Australian governments could place climate action above all else as the EU is doing, they would risk community and political blowback. Long-term progress means doing the work to secure local support.

For instance, Victoria’s new Transmission Investment Framework brings communities to the fore, focusing on their role and what they will stand to gain early on.

Yes, this approach may slow the rate at which wind turbines go up and solar is laid down. But it may ensure public support over the long term.

No one said the shift to green energy would be easy. Only that it is necessary, worthwhile – and possible. ![]()

Anne Kallies, Senior Lecturer in Energy Law, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Friday, 14 June 2024

'Europe in miniature': Welcome to Baarle, world's strangest border

Tuesday, 4 June 2024

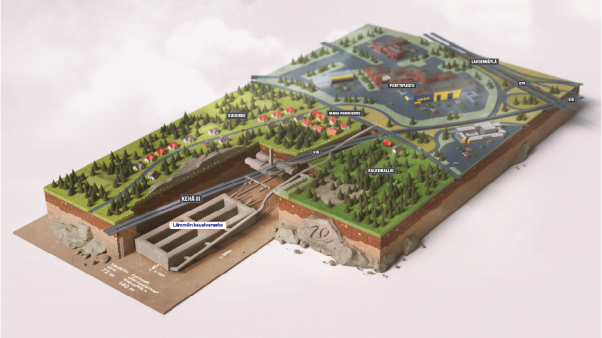

Waste Heat Generated from Electronics to Warm Finnish City in Winter Thanks to Groundbreaking Thermal Energy Project

Wednesday, 29 May 2024

For Europe to emulate Silicon Valley’s tech success, it should change its startup funding model

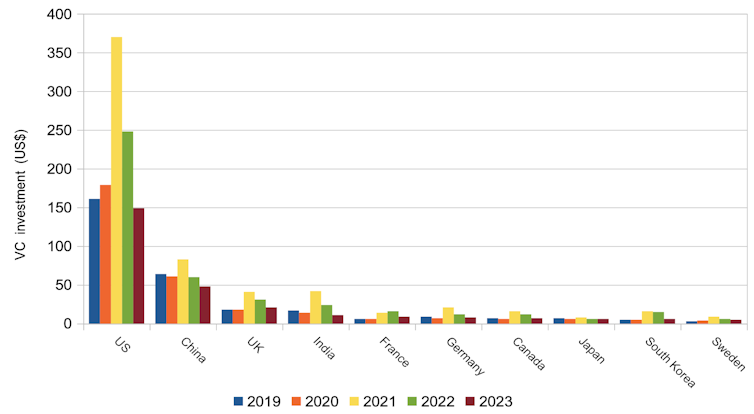

Tech startups will be enthused by the news that Silicon Valley venture capital (VC) veteran General Catalyst is on the verge of raising US$6 billion (£4.8 billion) for backing new companies. It comes hot on the heels of an announcement from Andreessen Horowitz, another major VC, of a new US$7.2 billion investment fund. These are among the largest fundraisings in years, coming at a time when the VC sector has been going through a lull, with worldwide total investments down from US$644 billion in 2021 to US$286 billion in 2023.

You can listen to more articles from The Conversation, narrated by Noa.

The bad news, depending on where you live, is that most of the proceeds are likely to be invested Stateside. American startups mop up around half of all global VC funding, while Europe and the UK are lucky to see a quarter. This is despite the fact that Europe and the UK have a slightly larger share of world GDP than the US (17% v 16%).

VC investment by country (US$)

This helps to explain why America’s leading three tech firms, Microsoft, Apple and Nvidia, are worth around US$7.5 trillion, while Europe’s equivalents, ASML, SAP and Prosus, are worth some US$700 billion. So what can be done to change this situation?

Silicon Valley’s edge

Silicon Valley’s success can be attributed to a range of mutually reinforcing factors, many of which planted their seeds decades ago. These include lucrative government contracts, entrepreneurial universities nearby, and the accumulation of wealth and talent from tech giants such as Apple, Nvidia, and OpenAI. This kind of head start is difficult to replicate.

US investors often plough millions of dollars into relatively early-stage companies, which are sums that other ecosystems simply cannot match. But startups typically first need to demonstrate traction with customers, usually in the form of sales revenue or user numbers. This is different from tech investment hubs such as Berlin and Scotland, where investors tend to only require a strong team with just an idea for the startup to be considered to have good potential for investment. Our research suggests that this might be an underappreciated reason for Silicon Valley’s success.

Having done in-depth interviews with 63 entrepreneurs and investors across Silicon Valley and Berlin, the different expectations of investors are very noticeable. For instance, the founders of San Francisco-based AirBnb had to use their credit cards to keep the company afloat, and even resorted to selling cereal boxes before eventually securing funding.

Similarly, the founders of food delivery app DoorDash, which is also based in San Francisco, built a full prototype and were making the deliveries themselves for nearly half a year before raising their first round of investment.

And yet, between 2020 and 2022, US$44 billion was invested in early-stage deals in Silicon Valley as opposed to US$5.8 billion in Berlin. Equally, roughly 31% of US but only 19% of European seed-stage startups progress to the next round of fundraising.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that the companies that do not raise follow-on funding fail, but it may help explain why Silicon Valley’s exits amount to US$403 million on average, as opposed to US$53 million in Berlin.

So why is it not the case that US startups struggle more when they have to meet higher expectations to get funded? And could other ecosystems catch up by adopting the same strategy?

The ‘valley of death’

The journey of a business idea from inception to early traction is often referred to as the “valley of death”. During this period, the startup needs to keep developing the business, build the product, and figure out a reliable business model. There is no one-size-fits-all blueprint and many companies fail, either because the idea is not viable or they run out of money.

Silicon Valley’s preferred funding model of investing into startups with traction somewhat decreases the risk of failure for VCs. In the long term this should result in more funds for reinvesting into new startups, which likely helped the whole ecosystem to flourish. There’s also a benefit to those entrepreneurs who can delay fundraising until they can demonstrate traction, since the startup is likely to be worth more. This means they can get more money or give up a smaller percentage of the business.

This would suggest that European startup ecosystems ought to think about moving towards this model. But it comes with a major downside. Few entrepreneurs have enough money to maintain the company through the valley of death – and it tends to be longer and deeper for the most innovative ideas. This is particularly an issue for entrepreneurs from under-represented groups, such as disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds, women and immigrants, who are less likely to have the necessary resources or connections. Thus, adopting the American investment threshold could make the startup world even more inaccessible to them.

To get the benefits of the US system without damaging diversity, there need to be support structures in place, such as incubator and accelerator programmes, to help startups gain traction. Even so, these need to be designed carefully to ensure they signal credibility, and therefore help – rather than hinder – the incubated companies to secure their first round of investment.![]()

Michaela Hruskova, Lecturer in Entrepreneurship, University of Stirling and Katharina Scheidgen, Chair of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Wednesday, 15 May 2024

UK SMBs could save 280m tonnes of CO2e by hitting 2030 targets