Tuesday, 30 December 2025

Couple Who Started IVF Last Christmas Day Welcomed a Baby After 11 Year Battle

Thursday, 25 December 2025

Boy Sent to Christmas Nativity Show as Elvis Instead of Elf After Family Mix-up

Tuesday, 4 November 2025

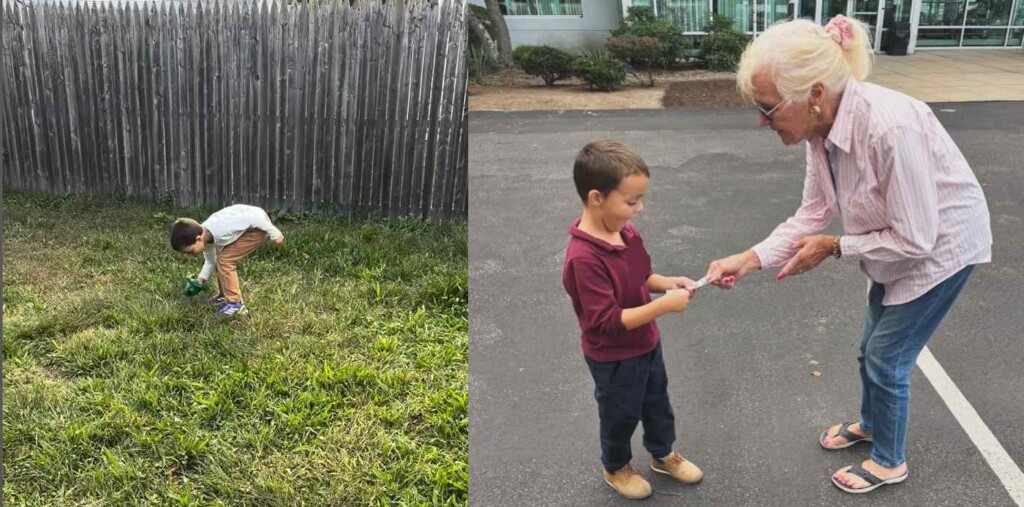

A 9-Year-Old Son Saves His Father from Leukemia by Donating Stem Cells

Thursday, 10 July 2025

Dozens of Free Summer Camps Opened By Paul Newman Give Sick Kids and Their Families ‘Serious Fun’

Tuesday, 8 July 2025

Rescued Crow Is Boy’s Best Friend, Waiting for Him to Get Home from School Every Day: ‘We’re his flock’

Otto and Russell – Courtesy of @laerke_luna on Instagram

Otto and Russell – Courtesy of @laerke_luna on InstagramSaturday, 28 June 2025

Four-year-old Credited with Saving Her Teacher’s Life at Tennessee Daycare

The lifesaver, Kyndal Bradley – credit, family photo

The lifesaver, Kyndal Bradley – credit, family photoMonday, 16 June 2025

UK to Lift 100,000 Kids From Poverty With Free School Lunches for All Low Income Households

– credit Curated Lifestyle for Unsplash +

– credit Curated Lifestyle for Unsplash +Wednesday, 28 May 2025

Whatever happened to Barbie’s feet? Podiatrists studied 2,750 dolls to find out

What do you get when a group of podiatrists (and shoe lovers) team up with a Barbie doll collector? A huge opportunity to explore how Barbie reflects changes in the types of shoes women wear.

It all started with the blockbuster Barbie movie in 2023. In particular, we discussed a scene when Barbie was distressed to find she didn’t have to walk on tip-toes. She could walk on flat feet.

Soon, we had designed a research project to study the feet of Barbie dolls on the market from her launch in 1959 to June 2024. That’s 2,750 Barbies in all.

How this scene from the Barbie movie inspired our research project.

In our study published today, we found a general shift away from Barbie’s iconic feet – on tip-toes, ready to slip on high-heeled shoes – to flat feet for flat shoes.

We found, like many women today, Barbie “chooses” her footwear depending on what she has to do – flats for skateboarding or working as an astronaut but heels when dressing up for a night out.

We also question whether high heels that Barbie and some women choose to wear are really as bad for your health as we’ve been led to believe.

The movie that sparked the #barbiefootchallenge

Barbie’s feet – in particular her tip-toe posture – triggered TikTok’s #barbiefoottrend and #barbiefootchallenge. When the movie was released, fans made videos to re-create how Barbie stepped out of her high-heeled shoes, yet stayed on tip-toes. Margot Robbie, the Australian actor who played Barbie in the movie, was even interviewed about it.

Despite the obvious interest in Barbie’s iconic foot stance, there had been no specific research on her feet or choice of footwear.

So our research team decided to look at how Barbie’s feet had changed over the years to reflect the kinds of shoes she’s worn, and how that ties in with her different jobs and growing diversity.

What we did

One of our research team has an extensive Barbie doll collection. This guided our search through online catalogues to examine the foot positions of 2,750 Barbie dolls.

Our custom-made audit tool allowed us to classify Barbie’s foot posture as tip-toe (known as equinus) or flat.

We also looked at when the dolls were made, whether they were diverse or inclusive (for instance, represented people with disabilities), and whether Barbie was employed.

We were surprised that Barbie’s high-heel wearing foot posture was no longer the norm. Barbie does, however, still wear high heels when dressed for fun.

We found, just like Barbie in the movie, she’s made a transition from high heels (equinus foot posture) to flat shoes (flat foot posture), especially when employed.

We suggest this mirrors broader societal changes. This includes how women choose footwear according to how much they have to move in the day, and away from only wearing high heels in some workplaces.

Barbie ditched her high-heel wearing foot posture as she climbed the career ladder. In the 1960s, all Barbies tip-toed around, but by the 2020s, only 40% did.

Meanwhile, her resume expanded, going from not being represented as having a job to 33% representing real-world jobs.

She was an astronaut in 1965, before the Moon landing, and a surgeon when the vast majority of doctors in the United States were men.

US laws changed in the late 80s, supporting women to own businesses without a man’s permission. And Barbie mirrored this.

She started trading stilettos for flats and strutting into male-dominated fields. Barbie didn’t just break the mould, she kicked it off with low-heeled shoes.

Barbie also evolved to better reflect the population. We found a moderate link between her having flat feet and representing diversity or disability.

For example, she chooses a stable flat shoe when using a prosthetic limb. But it was also great to see her break footwear stereotypes by wearing high heels when using a wheelchair.

Are high heels so bad?

Some celebrities, the media and public health advice warn against wearing high heels. But we know women (and Barbie) choose to wear them from time to time. In fact it’s discussions about women’s shoe choices that also gave us the idea for this fun research.

For instance, health professionals often link high-heeled shoes with developing bunions, knee osteoarthritis, back pain or being injured.

However bunions, and knee and back pain are just as common in people who don’t wear high heels.

Studies exploring the risk of high heels are also often performed with people who don’t usually wear high heels, or during competitive sports.

We couldn’t find any investigations exploring the long-term effect of wearing high heels.

Research does show that high-heeled shoes make you walk slower and make it harder to balance.

But high heels have different features, such as heel height or shape. So different types of high heels probably present a different risk. That risk also probably differs from person to person, including how often they walk in heels.

Lessons for all shoe lovers

But back to Barbie and lessons we learned. We know Barbie is a social construct that reflects some aspects of the real world. She chooses heels when fashion is the goal and flat shoes when needing speed and stability.

Rather than demonise high heels, messages about footwear need to evolve to acknowledge choice, and trust women can balance their own priorities and needs.

As Barbie’s journey shows, women already make thoughtful shoe choices based on comfort, function and identity.![]()

Cylie Williams, Professor, School of Primary and Allied Health Care, Monash University and Helen Banwell, Senior lecturer in Podiatry, University of South Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Thursday, 22 May 2025

Child Born with Heart Outside Chest Becomes Solitary Survivor Thanks to Surgical Procedure Invented for Her

Vanellope with her mom – credit, supplied by the family

Vanellope with her mom – credit, supplied by the family SWNS

SWNSWednesday, 14 May 2025

How to learn a language like a baby

Learning a new language later in life can be a frustrating, almost paradoxical experience. On paper, our more mature and experienced adult brains should make learning easier, yet it is illiterate toddlers who acquire languages with apparent ease, not adults.

Babies start their language-learning journey in the womb. Once their ears and brains allow it, they tune into the rhythm and melody of speech audible through the belly. Within months of birth, they start parsing continuous speech into chunks and learning how words sound. By the time they crawl, they realise that many speech chunks label things around them. It takes over a year of listening and observing before children say their first words, with reading and writing coming much later.

However, for adults learning a foreign language, the process is typically reversed. They start by learning words, often from print, and try to pronounce them before grasping the language’s overall sound.

Tuning in to a new language

Our new study shows that adults can quickly pick up on the melodic and rhythmic patterns of a completely novel language. It confirms that the relevant native-language acquisition mechanism remains intact in the adult brain.

In our experiment, 174 Czech adults listened to 5 minutes of Māori, a language they had never heard. They were then tested on new audio clips from either Māori or Malay – another unfamiliar but similar language – and asked to say if they were hearing the same language as before or not.

The test phrases were acoustically filtered to mimic speech heard in the womb. This preserved melody and rhythm, but removed the frequencies higher than 900 Hz which contain consonant and vowel detail.

Listeners correctly distinguished the languages more often than not, showing that even very brief exposure was enough for them to implicitly grasp a language’s melodic and rhythmic patterns, much like babies do.

However, during the exposure phase, only one group of participants simply listened – three other groups listened while reading subtitles. The subtitles were either in the original Māori spelling where speech sounds consistently map onto specific letters (similar to Spanish), altered to reduce sound-letter correspondence (like in English, for example “sight”, “site”, “cite”), or they were transliterated to a script unknown to any of the participants (Hebrew).

The results showed that reading alphabetic spellings actually hampered the adults’ sensitisation to the overall melody and rhythm of the novel language, reducing their test performance. As complete beginners, the participants were able to learn more Māori without textual aids of any kind.

Initial illiteracy helps learning

Our research builds on previous studies, which have found that spelling can interfere with how learners pronounce individual vowels and consonants of a non-native language. Examples among learners of English include Italian learners lengthening double letters, or Spaniards confusing words like “sheep” and “ship” due to how “i” and “e” are read in Spanish.

Our study shows that spelling can even hinder our natural ability to listen to speech melody and rhythm. Experts looking for ways to reawaken adults’ language-learning capabilities should therefore consider the potentially negative impact of premature exposure to alphabetic spelling in a foreign language.

Early studies have proposed that a putative “sensitive period” for acquiring the sound patterns of a language ends around age 6. Not coincidentally, this is the age when many children learn to read. There is also research on infants that shows that starting with the global features of speech, such as its melody and rhythm, serves as a gateway to other levels of the native language.

A reversed approach to language learning – one that begins with written forms – may indeed undercut adults’ sensitisation to the melody and rhythm of a foreign language. It affects their ability to perceive and produce speech fluently and, by extension, other linguistic competences like grammar and vocabulary usage.

A study with first- and third-graders confirms that illiterate children learn a new language differently from literate children. Non-readers were much better at learning which article went with which noun (like in the Italian “il bambino” or “la bambina”) than at learning individual nouns. In contrast, readers’ learning was influenced by the written form, which puts a space between articles and nouns.

Learn like a baby

Listening without reading letters may help us to stop focusing on individual vowels, consonants and separate words, and instead absorb the overall flow of a language much like infants do. Our research suggests that adult learners might benefit from adopting a more auditory-focused approach – engaging with spoken language first before introducing reading and writing.

The implications for language teaching are significant. Traditional methods often place a heavy emphasis on reading and writing early on, but a shift toward immersive listening experiences could accelerate spoken proficiency.

Language learners and educators alike should therefore consider adjusting their methods. This means tuning in to conversations, podcasts, and native speech from the earliest stage of language learning, and not immediately seeking out the written word.![]()

Kateřina Chládková, Assistant professor, Charles University; Šárka Šimáčková, assistant professor, Palacky University Olomouc, and Václav Jonáš Podlipský, Assistant Professor of English Phonetics, Palacky University Olomouc

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Children in need of ‘rescuing’: challenging the myths at the heart of the global adoption industry

Korean adoptees worldwide are grappling with a devastating possibility: they were not truly orphans, but may have been made into orphans.

For decades, adoptees were told they were “abandoned”, “rescued” or “unwanted”. Many were told their Korean families were too “poor” or “incapable” to raise them – and they should only ever feel grateful for being adopted.

But these long-held stories are now under scrutiny.

Our recent research interrogates the narratives that have obscured the darker realities of intercountry adoption. Rather than viewing adoption solely through the lens of “rescue”, our work examines the broader power structures that facilitated the mass migration of Korean children to western countries, including Australia.

South Korea’s reckoning with its adoption history

In March, South Korea’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission released its preliminary findings after collecting records and testimony from a coalition of overseas Korean adoptee-led organisations (including the Australia–US Korean Rights Group).

The preliminary report revealed a disturbing pattern of human rights violations in the country’s adoption industry, including:

- forced relinquishments

- falsified records

- babies switched at adoption

- inadequate screening processes, and

- deep-rooted institutional corruption.

The commission’s chair described finding

serious violations of the rights of adoptees, their biological parents – particularly Korean single mothers – and others involved. These violations should never have occurred.

The commission is expected to release its final report soon, but due to the upcoming presidential election and political uncertainty in South Korea, the timeline remains unclear.

Chilling cases

This is not the first time intercountry adoption has made headlines for irregularities, human rights abuses, or illicit and illegal practices.

While Australia was expanding the number of children for intercountry adoption from South Korea in the 1980s, Park In-keun – director of South Korea’s infamous Brothers Home, an illegal detention facility that sent children overseas for adoption – was arrested for embezzlement and illegal confinement.

He was ultimately acquitted of the most serious charges in South Korea before escaping to Australia. He was then charged again in 2014 for embezzlement, including government subsidies and wages of inmates forced into slave labour in South Korea. He died two years later.

Other allegations of human rights violations and abuses came to light around the same time with the arrest of Julie Chu.

She was accused of facilitating a “baby export” syndicate. Children were believed to have been kidnapped from Taiwan to send to Western countries, including Australia, in the 1970s and 80s. She was convicted of forgery, but denied being involved in trafficking.

Since then, other cases have continued to emerge involving countries such as Chile, Sri Lanka, India, Ethiopia and Guatemala.

What is the adoption industrial complex?

Intercountry adoption is not just a social practice. It’s also an economic and political system sometimes known as the transnational adoption industrial complex.

This network of organisations, institutions, government policies and financial systems created a globalised adoption economy worth billions of dollars. According to numerous investigations, Western nations, as “receiving” countries, drove the demand for the continuous sourcing of children.

As Park Geon-Tae, a senior investigator with South Korea’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, said:

To put it simply, there was supply because there was demand.

Australia received an estimated 3,600 Korean children from the 1970s to the present, as part of more than 10,000 intercountry adoptions.

Prospective parents typically paid between US$4,500 and $5,000 to facilitate acquiring a child in Australia in the 1980s, equivalent to A$21,000 today.

Since colonisation, Australia has had a long and painful history of child removal. From the Stolen Generations involving First Nations children to the forced adoption of children born to unwed mothers, child separation has been deeply embedded in the nation’s social policy.

While national apologies have acknowledged the irreparable harms caused by these policies, the same ideologies and structures were repurposed as the blueprint for intercountry adoption.

In recent years, other western nations, such as Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Sweden and Switzerland, have begun to investigate their own roles in the intercountry adoption industry. These nations have either suspended their adoption programs, issued formal apologies or launched formal investigations.

Thus far, Australia and the United States have not.

Challenging the ‘rescue’ myth

Intercountry adoption has long been framed as a humanitarian act. The central idea was that children needed “rescuing” and any life in a Western country would be “better” than one with their families in their home country.

Many adoptees and their original families were expected to just move on or be grateful for being “saved”.

However, research shows this gratitude narrative disregards the deep trauma caused by forced separation.

Studies have reported that adoptees experience lifelong ruptures due to cultural, familial and ancestral displacement. Forced assimilation makes reconnection with family and culture complex or nearly impossible.

Many intercountry adoptees have also voiced concerns about abuse, violence and mistreatment in adoptive homes.

Questioning the ‘orphan crisis’ myth

The myth of a global orphan crisis has also been a powerful driver of intercountry adoption.

Adoption groups often reference outdated UNICEF estimates that there are 150 million orphans globally. However, this figure obscures the fact most of the children classified as “orphans” are children of single parents, or children currently living in homes with extended family or other caregivers.

This was the case in South Korea. Most children sent for adoption were not true orphans, but children who had at least one parent or extended family they could have stayed with if they were adequately supported.

The belief that millions of children of single parents were “orphans” in need of “rescue” was used to justify calls for faster, less regulated adoptions.

Labelling these children as “orphans” also helped attract millions of dollars in philanthropic donations. However, donors were rarely interested in supporting children to stay with their families and communities in their home countries.

Instead, the focus was often on removing and migrating them for the purpose of intercountry adoption.

The question then emerges: was this about finding families for babies or finding babies for Western families?![]()

Samara Kim, PhD Candidate & Researcher, Southern Cross University; Kathomi Gatwiri, Associate Professor, Southern Cross University, and Lynne McPherson, Associate Professor, Southern Cross University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tuesday, 1 April 2025

Girl Joins Mensa at 13 After Scoring Higher Than Albert Einstein–Even with No Exam Prep

SWNS

SWNS SWNS

SWNSTuesday, 11 March 2025

10-Year-old Paramedic Teaches Adults Lifesaving Skills and CPR as ‘The Mini Medic’

Monday, 10 February 2025

How to watch a scary movie with your child

Carol Newall, Macquarie University

On Halloween, the cinemas and TV channels are filled with horror movies. But what should you do if you have a young child who wants to watch too?

Many of us have a childhood memory of a movie that gave us nightmares and took us to a new level of fear. Maybe this happened by accident. Or maybe it happened because an adult guardian didn’t choose the right movie for your age.

For me it was The Exorcist. It was also the movie that frightened my mum when she was a youngster. She had warned me not to watch it. But I did. I then slept outside my parents’ room for months for fear of demonic possession.

Parents often ask about the right age for “scary” movies. A useful resource is The Australian Council of Children and the Media, which provides colour-coded age guides for movies rated by child development professionals.

Let’s suppose, though, that you have made the decision to view a scary movie with your child. What are some good rules of thumb in managing this milestone in your child’s life?

Watch with a parent or a friend

Research into indirect experiences can help us understand what happens when a child watches a scary movie. Indirect fear experiences can involve watching someone else look afraid or hurt in a situation or verbal threats (such as “the bogeyman with sharp teeth will come at midnight for children and eat them”).

Children depend very much on indirect experiences for information about danger in the world. Scary movies are the perfect example of these experiences. Fortunately, research also shows that indirectly acquired fears can be reduced by two very powerful sources of information: parents and peers.

In one of our recent studies, we showed that when we paired happy adult faces with a scary situation, children showed greater fear reduction than if they experienced that situation on their own. This suggests that by modelling calm and unfazed behaviour, or potentially even expressing enjoyment about being scared during a movie (notice how people burst into laughter after a jump scare at theatres?), parents may help children be less fearful.

There is also some evidence that discussions with friends can help reduce fear. That said, it’s important to remember that children tend to become more similar to each other in threat evaluation after discussing a scary or ambiguous event with a close friend. So it might be helpful to discuss a scary movie with a good friend who enjoys such movies and can help the child discuss their worries in a positive manner.

Get the facts

How a parent discusses the movie with their child is also important. Children do not have enough experience to understand the statistical probability of dangerous events occurring in the world depicted on screen. For example, after watching Jaws, a child might assume that shark attacks are frequent and occur on every beach.

Children need help to contextualise the things they see in movies. One way of discussing shark fears after viewing Jaws might be to help your child investigate the statistics around shark attacks (the risk of being attacked is around 1 in 3.7 million) and to acquire facts about shark behaviours (such as that they generally do not hunt humans).

These techniques are the basis of cognitive restructuring, which encourages fact-finding rather than catastrophic thoughts to inform our fears. It is also an evidence-based technique for managing excessive anxiety in children and adults.

Exposure therapy

If your child is distressed by a movie, a natural reaction is to prevent them watching it again. I had this unfortunate experience when my seven-year-old daughter accidentally viewed Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children, which featured a monster with knives for limbs who ate children’s eyeballs for recreation.

My first instinct was to prevent my daughter watching the movie again. However, one of the most effective ways of reducing excessive and unrealistic fear is to confront it again and again until that fear diminishes into boredom. This is called exposure therapy.

To that end, we subjected her and ourselves to the same movie repeatedly while modelling calm and some hilarity - until she was bored. We muted the sound and did silly voice-overs and fart noises for the monster. We drew pictures of him with a moustache and in a pair of undies. Thankfully, she no longer identifies this movie as one that traumatised her.

This strategy is difficult to execute because it requires tolerating your child’s distress. In fact, it is a technique that is the least used by mental health professionals because of this.

However, when done well and with adequate support (you may need an experienced psychologist if you are not confident), it is one of the most effective techniques for reducing fear following a scary event like an accidental horror movie.

Fear is normal

Did I ever overcome my fear of The Exorcist? It took my mother checking my bed, laughing with me about the movie, and re-affirming that being scared is okay and normal for me to do so (well done mum!)

Fear is a normal and adaptive human response. Some people, including children, love being scared. There is evidence that volunteering to be scared can lead to a heightened sense of accomplishment for some of us, because it provides us with a cognitive break from our daily stress and worries.

Hopefully, you can help ensure that your child’s first scary movie experience is a memorable, enjoyable one.![]()

Carol Newall, Senior Lecturer in Early Childhood, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Monday, 3 February 2025

Three Children Receive ‘the Best Christmas Present Ever’ – Bionic Arms

Colette Baker, Finley Jarvis, and Zoey Pidgeon-Hampton with their new Open Bionics arms – credit: SWNS

Colette Baker, Finley Jarvis, and Zoey Pidgeon-Hampton with their new Open Bionics arms – credit: SWNSWednesday, 22 January 2025

Anonymous $3.5 Million Gift to Milwaukee Art Museum Provides Free Admission for Children

The Milwaukee Art Museum’s Art:Forward Gala in 2024 – Credit: Front Room Studios and courtesy of the Milwaukee Art Museum.

The Milwaukee Art Museum’s Art:Forward Gala in 2024 – Credit: Front Room Studios and courtesy of the Milwaukee Art Museum.Tuesday, 31 December 2024

Torn Between Volunteering and Dream of Adopting a Cat, 6-year-old Starts Poop Scooping Business

Monday, 9 December 2024

Woman Gives Birth in Lobby of Welsh Cinema and the Daughter Now Has Free Movies for Life

Wednesday, 4 December 2024

Shortsightedness is on the rise in children. There’s more we can do than limit screen time

Myopia in children is on the rise. The condition – also known as shortsightedness – already affects up to 35% of children across the world, according to a recent review of global data. The researchers predict this number will increase to 40%, exceeding 740 million children living with myopia by 2050.

So why does this matter? Many people may be unaware that treating myopia (through interventions such as glasses) is about more than just comfort or blurry vision. If left unchecked, myopia can rapidly progress, increasing the risk of serious and irreversible eye conditions. Diagnosing and treating myopia is therefore crucial for your child’s lifetime eye health.

Here is how myopia develops, the role screen time plays – and what you can do if think your child might be shortsighted.

What is myopia?

Myopia is commonly known as nearsightedness or shortsightedness. It is a type of refractive error, meaning a vision problem that stops you seeing clearly – in this case, seeing objects that are far away.

A person usually has myopia because their eyeball is longer than average. This can happen if eyes grow too quickly or longer than normal.

A longer eyeball means when light enters the eye, it’s not focused properly on the retina (the light-sensing tissue lining the back of the eye). As a result, the image they see is blurry. Controlling eye growth is the most important factor for achieving normal vision.

Myopia is on the rise in children

The study published earlier this year looked at how the rate of myopia has changed over the last 30 years. It reviewed 276 studies, which included 5.4 million people between the ages of 5–19 years, from 50 countries, across six continents.

Based on this data, the researchers concluded up to one in three children are already living with shortsightedness – and this will only increase. They predict a particular rise for adolescents: myopia is expected to affect more than 50% of those aged 13-19 by 2050.

Their results are similar to a previous Australian study from 2015. It predicted 36% of children in Australia and New Zealand would have myopia by 2020, and more than half by 2050.

The new review is the most comprehensive of its kind, giving us the closest look at how childhood myopia is progressing across the globe. It suggests rates of myopia are increasing worldwide – and this includes “high myopia”, or severe shortsightedness.

What causes myopia?

Myopia develops partly due to genetics. Parents who have myopia – and especially high myopia – are more likely to have kids who develop myopia as well.

But environmental factors can also play a role.

One culprit is the amount of time we spend looking at screens. As screens have shrunk, we tend to hold them closer. This kind of prolonged focusing at short range has long been associated with developing myopia.

Reducing screen time may help reduce eye strain and slow myopia’s development. However for many of us – including children – this can be difficult, given how deeply screens are embedded in our day-to-day lives.

Green time over screen time

Higher rates of myopia may also be linked to kids spending less time outside, rather than screens themselves. Studies have shown boosting time outdoors by one to two hours per day may reduce the onset of myopia over a two to three year period.

We are still unsure how this works. It may be that the greater intensity of sunlight – compared to indoor light – promotes the release of dopamine. This crucial molecule can slow eye growth and help prevent myopia developing.

However current research suggests once you have myopia, time outdoors may only have a small effect on how it worsens.

What can we do about it?

Research is rapidly developing in myopia control. In addition to glasses, optometrists have a range of tools to slow eye growth and with it, the progression of myopia. The most effective methods are:

orthokeratology (“ortho-K”) uses hard contact lenses temporarily reshape the eye to improve vision. They are convenient as they are only worn while sleeping. However parents need to make sure lenses are cleaned and stored properly to reduce the chance of eye infections

atropine eyedrops have been shown to successfully slow myopia progression. Eyedrops can be simple to administer, have minimal side effects and don’t carry the risk of infection associated with contact lenses.

What are the risks with myopia?

Myopia is easily corrected by wearing glasses or contact lenses. But if you have “high myopia” (meaning you are severely shortsighted) you have a higher risk of developing other eye conditions across your lifetime, and these could permanently damage your vision.

These conditions include:

retinal detachment, where the retina tears and peels away from the back of the eye

glaucoma, where nerve cells in the retina and optic nerve are progressively damaged and lost

myopic maculopathy, where the longer eyeball means the macula (part of the retina) is stretched and thinned, and can lead to tissue degeneration, breaks and bleeds.

What can parents do?

It’s important to diagnose and treat myopia early – especially high myopia – to stop it progressing and lower the risk of permanent damage.

Uncorrected myopia can also affect a child’s ability to learn, simply because they can’t see clearly. Signs your child might need to be tested can include squinting to see into the distance, or moving things closer such as a screen or book to see.

Regular eye tests with the optometrist are the best way to understand your child’s eye health and eyesight. Each child is different – an optometrist can help you work out tailored methods to track and manage myopia, if it is diagnosed.![]()

Flora Hui, Honorary Fellow, Department of Optometry and Vision Sciences, Melbourne School of Health Sciences, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.