Los Angeles, (IANS) The queen of pop, Madonna is celebrating the birthday of her son, David Banda. The singer-songwriter recently took to her Instagram, and shared a bunch of throwback pictures of herself with her son from his childhood to teenage.

For a supposedly obsolete music format, audio cassette sales seem to be set on fast forward at the moment.

Cassettes are fragile, inconvenient and relatively low-quality in the sound they produce – yet we’re increasingly seeing them issued by major artists.

Is it simply a case of nostalgia?

The cassette format had its heyday during the mid-1980s, when tens of millions were sold each year.

However, the arrival of the compact disc (CDs) in the 1990s, and digital formats and streaming in the 2000s, consigned cassettes to museums, second-hand shops and landfill. The format was well and truly dead until the past decade, when it started to reenter the mainstream.

According to the British Phonographic Industry, in 2022 cassette sales in the United Kingdom reached their highest level since 2003. We’re seeing a similar trend in the United States, where cassette sales were up 204.7% in the first quarter of this year (a total of 63,288 units).

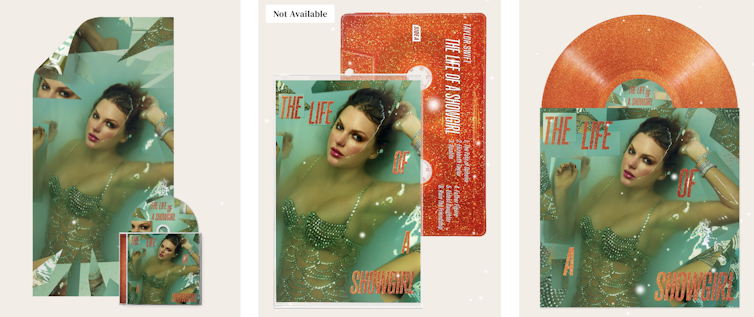

A number of major artists, including Taylor Swift, Billie Eilish, Lady Gaga, Charli XCX, the Weeknd and Royel Otis have all released material on cassette. Taylor Swift’s latest album, The Life of a Showgirl, is available in 18 versions across CDs, vinyl and cassettes.

The physical product offerings for Taylor Swift’s latest album, The Life of a Showgirl. Taylor Swift

The physical product offerings for Taylor Swift’s latest album, The Life of a Showgirl. Taylor SwiftMany news article will tell you a “cassette revival” is well underway. But is it?

I would argue what we’re seeing now is not a full-blown revival. After all, the unit sales still pale in comparison to the peak in the late 1990s, when some 83 million were reportedly sold in one year in the UK alone.

Instead, I see this as a form of rediscovery – or for young listeners, discovery.

Recorded music today is mostly heard through digital channels such as Spotify and social media.

Meanwhile, cassettes break and jam quite easily. Choosing a particular song might involve several minutes of fast forwarding, or rewinding, which clogs the playback head and weakens the tape over time. The audio quality is low, and comes with a background hiss.

Why resurrect this clunky old technology when everything you could want is a languid tap away on your phone?

Analogue formats such as cassettes and vinyl are not prized for their sound, but for the tactility and sense of connection they provide. For some listeners, cassettes and LPs allow for a tangible connection with their favourite artist.

There’s an old joke about vinyl records that people get into them for the expense and the inconvenience. The same could be said for cassette tapes: our renewed interest in them could be read as a questioning (if not rejection) of the blandly smooth, ubiquitous and inescapable digital world.

The joy of the cassette is its “thingness”, its “hereness” – as opposed to an intangible string of electrical impulses on a far-flung corporate-owned server.

The inconvenience and effort of using cassettes may even make for more focused listening – something the invisible, ethereal and “instantly there” flow of streaming doesn’t demand of us.

People may also choose to buy cassettes for the nostalgia, for their “retro” cool aesthetic, to be able to own music (instead of streaming it), and to make cheap and quick recordings.

Cassettes did (and still do) have the whiff of the rebel about them. As researcher Mike Glennon explains, they give consumers the power to customise and “reconfigure recorded sound, thus inserting themselves into the production process”.

From the 1970s, blank cassettes were a cheap way for anyone to record anything. They offered limitless combinations and juxtapositions of music and sounds.

The mix tape became an art form, with carefully selected track sequences and handmade covers. Albums could even be chopped up and rearranged according to preference.

Consumers could also happily copy commercial vinyl and cassettes, as well as music from radio, TV and live gigs. In fact, the first single ever released on cassette, Bow Wow Wow’s C30,C60,C90,Go! (1980), extolled the joys and righteousness of home taping as a way of sticking it to the man – or in this case the music industry.

Unsuprisingly, the recording industry saw cassettes and home taping as a threat to its copyright-based income and struck back.

In 1981, the British Phonographic Industry launched its infamous “home taping is killing music” campaign. But the campaign’s somewhat pompous tone led to it being mercilessly mocked and largely ignored by the public.

The idea of the blank cassette as both a symbol of self-expression and freedom from corporate control continues to persist. And today, it’s not only corporate control consumers have to dodge, but also the dominance of digital streaming platforms.

Far from being just a pleasant yearning sensation, nostalgia for older technology is layered, complex and often political.

Cassettes are cheap and easy to make, so many artists past and present have used them as merchandise to sell or give away at gigs and fan events. For hardcore fans, they are solid tokens of their dedication – and many fans will buy multiple formats as a form of collecting.

Cassettes won’t replace streaming services anytime soon, but that’s not the point. What they offer is a way of listening that goes against the grain of the digital hegemony we find ourselves in. That is, until the tape snaps.![]()

Peter Hoar, Senior Lecturer, School of Communications Studies, Auckland University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Thanks to the runaway global popularity of Netflix’s new animated film, KPop Demon Hunters, cinemas around the world have picked it up and are now screening a sing-along edition.

Huntr/x, the musical girl group featured in the story, has topped charts worldwide with their track Golden.

As the film smashes records and captures audiences everywhere, one question lingers: what makes this animation stand out from the rest? An answer lies in how relatable the main characters are.

The film follows three K-pop girl group members who use their music and voices to protect the world from demonic forces. While the storyline centres on the fantastical notion of “demon hunters”, grounding the protagonists in the guise of K-pop idols adds on-trend authenticity. As co-director Chris Appelhans explained, the aim was “making girls act like real girls, and not just pristine superheroes”.

Rather than dwelling solely on their heroics, the film portrays the characters’ everyday moments and ordinary behaviour. Food, clothes and familiar locations in South Korea are rendered with surprising precision, to the extent that even Korean audiences are astonished at their accuracy, despite the production being based overseas.

But how closely does the film’s version of K-pop reflect the real thing?

Take the first appearance of Huntr/x members Rumi, Mira and Zoey: with only minutes to go before a performance, they are shown devouring kimbap, ramen, fish cakes and snacks – fuel for the stage. In reality, idols may often end up grabbing a quick bite of kimbap or ramen in the car between packed schedules. More commonly, however, strict diets are the norm. There are reports that sometimes trainees – aspiring K-pop idols who are part of an entertainment company’s training programme – are even forced to shed weight by agencies: one of the industry’s darker aspects.

Yet, as idols mature, many develop their own healthier routines, not simply for looks but to ensure longevity in their careers.

Meanwhile, in the case of boy group Saja Boys, the film highlights the fans’ fascination with their sculpted abs. In reality, male idols often put themselves through intense workouts to build impressive physiques, showing off toned bodies and six-packs on stage for their fans.

Then there is the question of accommodation. In the film, Huntr/x members share a luxurious penthouse overlooking Seoul’s skyline. In reality, agencies often provide dorm accommodation to facilitate scheduling and teamwork, usually near the company, and often managers live with artists. The quality varies greatly, with newcomers typically placed in modest housing.

After debut, successful idols may upgrade their accommodation as the money starts to roll in, but a penthouse, as shown in the film, is more fantasy than fact. BTS being a notable exception, progressing from sharing a converted office (not even a proper house) to one of Seoul’s most prestigious apartments. Most idols tend to strike out on their own some years after debut, balancing solo activities with personal life. By then, their choice of home usually reflects their individual earnings.

The film mirrors K-pop reality in other respects. One Huntr/x member, Zoey, is Korean-American – reflecting the industry’s trend since the 2000s towards multinational line-ups designed to create a global audience. Blackpink, for instance, includes two Korean members with overseas backgrounds and one foreign national, which has bolstered their international reach.

The film also shows Zoey writing and composing songs: many idols are now singer-songwriters. With the industry demanding constant renewal, the shelf life of an “idol” is very short. Writing and producing music has become both a way to extend careers and secure additional income streams. BTS are all credited songwriters, while figures such as BigBang’s G-Dragon, Block B’s Zico, and i-dle’s Soyeon have all built reputations – and royalties – through their creative work.

Increasingly, even K-pop trainees now learn songwriting and production before their debut. Beyond these points, the film captures a wide slice of K-pop culture as it really exists – from fan sign events to the sea of light sticks waving at concerts.

More than any other element, it’s the music that gives the film its sharpest sense of realism.

Executive music producer Ian Eisendrath teamed up with record label THEBLACKLABEL to produce K-pop tracks that sound right at home in the current charts. Blending trendy and catchy hooks with the story itself has drawn in not only animation fans but also audiences lured by the music alone.

Co-director Maggie Kang put it plainly in an interview: “We really wanted to immerse the world in K-pop.” At the same time, she noted that the film deliberately heightens certain aspects of the genre. That kind of exaggeration is only natural in animation, where drama is part of the appeal. What matters is that every flourish is still grounded in reality.

For viewers familiar with Korean culture and K-pop, that means spotting a wealth of details that might otherwise go unnoticed – and it’s this layer of discovery that may well be among the key factors driving the popularity of KPop Demon Hunters.![]()

Cholong Sung, Lecturer in Korean, SOAS, University of London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Music producer put up a group photo at the Grammys on Instagram. PHOTO: Screenshot from Instagram via ANI

Music producer put up a group photo at the Grammys on Instagram. PHOTO: Screenshot from Instagram via ANI Chennai-born Chandrika Tandon wins Grammy for Best New Age AlbuM ‘Triveni’. PHOTO: Instagram @chandrikatandon

Chennai-born Chandrika Tandon wins Grammy for Best New Age AlbuM ‘Triveni’. PHOTO: Instagram @chandrikatandonMade in Korea: The K-Pop Experience is a six-part reality show following five British trainees over 100 days as they debut as a Korean-pop (K-pop) idol boy group called Dear Alice. In collaboration with SM Entertainment, a K-pop powerhouse, the show will introduce the behind-the-scenes of making a K-pop idol through an immersive training system.

Showing a glimpse of the lives of K-pop trainees, the first episode introduces K-pop as a multi-billion global phenomenon, stating: “Six of the top 20 best-selling artists in the world were K-pop and 90 billion streams were by K-pop idols.”

K-pop is becoming increasingly popular in the UK. Girl group Aespa and boy group BTS have sold out shows in the country’s largest arenas.

In 2023, the group Blackpink became the first Korean band to headline a UK festival at BST Hyde Park, where they played to an audience of 65,000. They were also awarded honorary MBEs by the king for their role in encouraging young people to engage with the global UN climate change conference at COP26 in Glasgow 2021.

There is certainly an appetite for shows about K-pop for western audiences. Netflix have released their own version of Made in Korea, Pop Star Academy: Katseye.

The docuseries follows 20 girls from Japan, South Korea, Australia and the UK going through a year of K-pop training to become the group Kasteye. It’s a collaboration between the K-pop label Hybe and US label Geffen (a subsidiary of Universal).

Generally speaking, K-pop is characterised by catchy and lively melodies and highly choreographed dance routines in perfect unison and fancy outfits. Inspired by various pop music genres – including but not limited to electronic dance, hip hop, and R&B – the genre became distinctive from the nation’s traditional music, especially after a handful of pioneers began producing idol groups in the 1990s.

I’m South Korean and I’m studying cultural industries, so it’s interesting for me to see westernerss becoming K-pop-inspired idol groups. It’s a famously competitive industry, which is already oversaturated with hopeful K-idols. Considering that the domestic market is small and highly saturated, their success will be a breakthrough for SM Entertainment and HYBE, as well as other K-pop companies, proving whether they can continue to grow beyond east Asia.

The production and delivery of this popular music genre have become more international than ever in recent years, with hundreds of choreographers, composers and producers worldwide contribute to creating K-pop songs and performances. In contrast, K-pop performers have until recently been predominantly Korean. But as the new shows demonstrate, this too is changing.

K-pop companies have hosted auditions outside the country to recruit foreign trainees to make their idols appeal to global audiences. Huge global music corporations like Sony, Universal Music Group and Virgin Records have also got in on the game, signing distribution contracts with major K-pop idols to promote their music in foreign markets.

This search isn’t because there is a lack of willing hopefuls in Korea. There were around an estimated 800 trainees waiting to debut in 2022. But Korea’s population is only around 50 million and record companies want to appeal beyond the domestic market, so they are hoping recruiting non-Korean stars will help do that.

Music agencies in the west tend to find new artists who are already gifted and then largely serve as intermediaries arranging things like tours, marketing and artists’ wider schedules. However, major K-pop companies have developed a unique system of finding and launching new artists. This involves hosting auditions with a competition of at least 1,000 to 1 odds. The winners then undergo years of of acting, vocal, and dance training before debuting.

To make the vocals flawless and the dance moves precise, trainees, known as yeonseupsaeng (연습생), are expected to spend up to 17 hours per day practising performances and training for several years – although they aren’t guaranteed to become professional artists. Even if they do become successful, their private lives – including their dating lives – are strictly controlled.

It is no exaggeration to say that the industry is labour-intensive as well as capital-intensive, built on the blood, sweat and tears of yeonseupsaeng.

The first episode of Made in Korea ends with SM’s director Hee Jun Yoon’s critique of the Britons’ first performance. It’s difficult viewing for those unfamiliar with the harsh world of K-pop. To borrow the words of BBC’s unscripted content head, Kate Phillips, it makes “Simon Cowell look like Mary Poppins.”

Some might question the prefix “K-” being used to describe these international groups but the genre will remain decidedly Korean. It is Korean companies which will lead the production mechanisms and the domestic market will continue to serve as the testbed for new artists. But the success of Dear Alice and Katseye is important if the genre is to survive and continue to grow beyond Korea.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.![]()

Taeyoung Kim, Lecturer in Communication and Media, Loughborough University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

LONDON - David Bowie's original handwritten lyrics for the pop classic "Starman", part of an album that catapulted him to international stardom, on Tuesday sold at auction in Britain for £203,500.

LONDON - David Bowie's original handwritten lyrics for the pop classic "Starman", part of an album that catapulted him to international stardom, on Tuesday sold at auction in Britain for £203,500.As the largest section of the orchestra, sitting front and centre of the stage performing memorable melodies, it’s easy for violinists to steal the limelight. Ask any violinist why there are so many in an orchestra, and we’ll often reply, tongue-in-cheek: “obviously it’s because we’re the best”.

The real answer is a bit more complex, and combines reasons both logistical and historical.

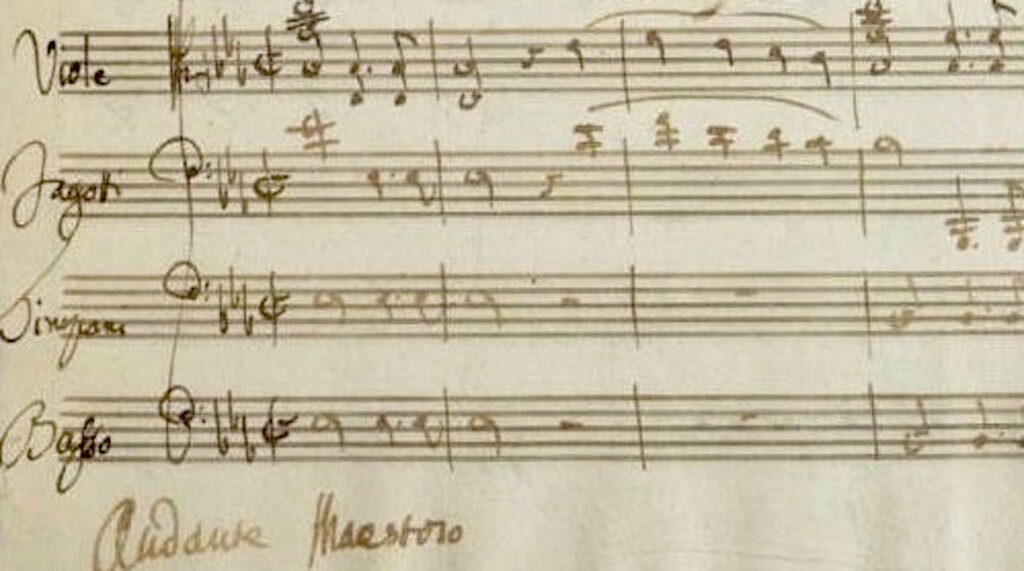

During the Baroque period between around 1600 and 1750, the composition of the orchestra was not standardised, and often used instruments based on availability. Monteverdi’s opera L'Orfeo, which premiered in 1607, is one of the earliest examples of a composer specifying the desired instrumentation.

The size of the orchestra also varied. Johann Sebastian Bach wrote for and worked with ensembles of up to 18 players in Germany. At Palazzo Pamphili in Rome, Corelli directed ensembles of 50–80 musicians – and, on one notable occasion to celebrate the coronation of Pope Innocent XII, an ensemble of 150 string players.

The modern-day violin was also developed around this time, and eventually replaced the instruments of the viol family. The violin has remained a staple member of the orchestra ever since.

Music of this period was created on a smaller scale than much of the repertoire we hear today, and often placed a strong focus on string instruments. As the orchestra became more standardised, members of the woodwind family appeared, including the oboe, bassoon, recorder and transverse flute.

During the classical period from around 1730 to 1820, orchestral performances moved from the royal courts into the public domain, and their size continued to grow. Instruments were organised into sections, and bowed strings formed the majority.

Composers began to use a wider range of instruments and techniques. Beethoven wrote parts for the early double bassoon, piccolo flute, trombone (which was largely confined to church music beforehand), and individual double bass parts (where previously they had often doubled the cello part).

During the romantic period of the 19th century, composer Hector Berlioz, author of a Treatise on Instrumentation and Modern Orchestration (1841), further developed the symphony orchestra by adding instruments such as the tuba, cor anglais and bass clarinet.

By the end of the 19th century, many orchestras reached the size and proportions we recognise today, with works that require more than 100 musicians, such as Wagner’s Ring Cycle.

As increasing numbers of performers and instruments became standard in orchestral repertoire, ensembles became louder, and more string players were needed to balance the sound. The violin is a comparatively quiet instrument, and a solo player cannot be heard over the power of the brass.

Having violinists at the front of the stage also helps the sound reach the audience’s ears without competing to be heard over the louder instruments.

The typical layout of the orchestra has not always been standard. First violinists (who often carry the melody) and second violinists (who typically play a supportive role) used to sit opposite each other on stage.

US conductor Leopold Stokowski rearranged the position of the first and second violinists during the 1920s so they sat next to each other on the left of the stage. This change meant the voices of each string section were arranged from high to low across the stage.

This change was widely adopted and has become a standard setup for the modern orchestra.

Stokowski is known for experimenting with the layout of the orchestra. He once placed the entire woodwind section at the front of the orchestra ahead of the strings, receiving widespread criticism from the audience and musicians. The board of the Philadelphia Orchestra allegedly said the winds “weren’t busy enough to put on a good show”.

String players do not need to worry about lung capacity or breaking for air. As such, violinists can perform long melodic passages with fast finger work, and our bows allow for seemingly endless sustain. Melodies written for strings are innumerable, and often memorable.

Having several violinists play together creates a specific sound and texture that is distinct from a solo string player and the other sections of the orchestra. Not only is the sound of every violin slightly different, the rate of each string’s vibration and the movement of each player’s bow varies. The result is a rich and full texture that creates a lush effect.

Today, symphony orchestras are expected to perform an incredibly diverse range of repertoire from classical to romantic, film scores to newly commissioned works. Determining the number of violinists who will appear in any given piece is a question of balance that will change depending on the repertoire.

A Mozart symphony might require fewer than ten wind or brass players, who would be drowned out by a full string section. However, a Mahler symphony requires more than 30 non-string players – meaning far more string players are needed to balance out this sound.

Notable exceptions to the orchestra’s standard setup include Charles Ives’ 1908 The Unanswered Question for string orchestra, solo trumpet and wind quartet spread around the room; Stockhausen’s 1958 Gruppen, pour trois orchestres, in which three separate orchestras perform in a horseshoe shape around the audience; and Pierre Boulz’s 1981 Répons featuring 24 performers on a stage surrounded by the audience, who are in turn surrounded by six soloists.

Despite experimentation, the placement and number of instruments in an orchestra has remained relatively standard since the 19th century.

Many aspects of the traditional orchestra’s setup make sense. However, many of the orchestra’s habits come down to tradition and perhaps unconscious alignment with “just the way things are done”.![]()

Laura Case, Lecturer in Musicology, Sydney Conservatorium of Music, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.