Friday, 6 February 2026

7.1 million cancer cases worldwide preventable, tobacco biggest culprit: WHO

Friday, 23 January 2026

Human heart regrows muscle cells after heart attack: Study

Wednesday, 14 January 2026

63 pc of Indian enterprises believe Gen AI is important for sustainability efforts: Study

Friday, 12 December 2025

Can you wear the same pair of socks more than once?

Primrose Freestone, University of Leicester

It’s pretty normal to wear the same pair of jeans, a jumper or even a t-shirt more than once. But what about your socks?

If you knew what really lived in your socks after even one day of wearing, you might just think twice about doing it.

Our feet are home to a microscopic rainforest of bacteria and fungi – typically containing up to 1,000 different bacterial and fungal species. The foot also has a more diverse range of fungi living on it than any other region of the human body.

The foot skin also contains one of the highest amount of sweat glands in the human body.

Most foot bacteria and fungi prefer to live in the warm, moist areas between your toes where they dine on the nutrients within your sweat and dead skin cells. The waste products produced by these microbes are the reason why feet, socks and shoes can become smelly.

For instance, the bacteria Staphylococcal hominis produces an alcohol from the sweat it consumes that makes a rotten onion smell. Staphylococcus epidermis, on the other hand, produces a compound that has a cheese smell. Corynebacterium, another member of the foot microbiome, creates an acid which is described as having a goat-like smell.

The more our feet sweat, the more nutrients available for the foot’s bacteria to eat and the stronger the odour will be. As socks can trap sweat in, this creates an even more optimal environment for odour-producing bacteria. And, these bacteria can survive on fabric for months. For instance, bacteria can survive on cotton for up to 90 days. So if you re-wear unwashed socks, you’re only allowing more bacteria to grow and thrive.

The types of microbes resident in your socks don’t just include those that normally call the foot microbiome home. They also include microbes that come from the surrounding environment – such as your floors at home or in the gym or even the ground outside.

In a study which looked at the microbial content of clothing which had only been worn once, socks had the highest microbial count compared to other types of clothing. Socks had between 8-9 million bacteria per sample, while t-shirts only had around 83,000 bacteria per sample.

Species profiling of socks shows they harbour both harmless skin bacteria, as well as potential pathogens such as Aspergillus, Candida and Cryptococcus which can cause respiratory and gut infections.

The microbes living in your socks can also transfer to any surface they come in contact with – including your shoes, bed, couch or floor. This means dirty socks could spread the fungus which causes Athlete’s foot, a contagious infection that affects the skin on and around the toes.

This is why it’s especially key that those with Athlete’s foot don’t share socks or shoes with other people, and avoid walking in just their socks or barefoot in gym locker rooms or bathrooms.

Foot hygiene

To cut down on smelly feet and reduce the number of bacteria growing on your feet and in your socks, it’s a good idea to avoid wearing socks or shoes that make the feet sweat.

Washing your feet twice daily may help reduce foot odour by inhibiting bacterial growth. Foot antiperspirants can also help, as these stop the sweat – thereby inhibiting bacterial growth.

It’s also possible to buy socks which are directly antimicrobial to the foot bacteria. Antimicrobial socks, which contain heavy metals such as silver or zinc, can kill the bacteria which cause foot odour. Bamboo socks allow more air flow, which means sweat more readily evaporates – making the environment less hospitable for odour-producing bacteria.

Antimicrobial socks might therefore be exempt from the single-use rule depending on their capacity to kill bacteria and fungi and prevent sweat accumulation.

But for those who wear socks that are made out of cotton, wool or synthetic fibres, it’s best to only wear them once to prevent smelly feet and avoid foot infections.

It’s also important to make sure you’re washing your socks properly between uses. If your feet aren’t unusually smelly, it’s fine to wash them in warm water that’s between 30-40°C with a mild detergent.

However, not all bacteria and fungi will be killed using this method. So to thoroughly sanitise socks, use an enzyme-containing detergent and wash at a temperature of 60°C. The enzymes help to detach microbes from the socks while the high temperature kills them.

If a low temperature wash is unavoidable then ironing the socks with a hot steam iron (which can reach temperatures of up to 180–220°C) is more than enough kill any residual bacteria and inactivate the spores of any fungi – including the one that causes Athlete’s foot.

Drying the socks outdoors is also a good idea as the UV radiation in sunlight is antimicrobial to most sock bacteria and fungi.

While socks might be a commonly re-worn clothing item, as a microbiologist I’d say it’s best you change your socks daily to keep feet fresh and clean.![]()

Primrose Freestone, Senior Lecturer in Clinical Microbiology, University of Leicester

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Friday, 28 November 2025

Would Your Helmet Actually Protect You? VA Tech’s ‘Helmet Lab’ Is Testing Every Sport

Friday, 21 November 2025

57% of young Australians say their education prepared them for the future. Others are not so sure

Lucas Walsh, Monash University

When we talk about whether the education system is working we often look at results and obvious outcomes. What marks do students get? Are they working and studying after school? Perhaps we look at whether core subjects like maths, English and science are being taught the “right” way.

But we rarely ask young people themselves about their experiences. In our new survey launched on Tuesday, we spoke to young Australians between 18 and 24 about school and university. They told us they value their education, but many felt it does not equip them with the skills, experiences and support they need for future life.

Our research

In the Australian Youth Barometer, we survey young Australians each year. In the latest report, we surveyed a nationally representative group of 527 young people, aged 18 to 24. We also did interviews with 30 young people.

We asked them about their views on the environment, health, technology and the economy. In this article, we discuss their views on their education.

‘They don’t teach you the realities’

In our survey, 57% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed their education had prepared them for their future. This means about two fifths (43%) didn’t agree or were uncertain.

Many said school made them “book smart” but didn’t teach essential life skills such as budgeting, taxes, cooking, renting or workplace readiness. As one 23-year-old from Queensland told us:

They don’t teach you the realities of life and being an adult.

This may explain why 61% of young Australians in our study had taken some form of online informal classes, such as a YouTube tutorial. Young people are looking to informal learning for acquiring practical skills such as cooking, household repairs, managing finances, driving and applying for jobs.

Some interviewees discussed how informal learning – outside of formal education places – was a key site for personal development. One interviewee (21) from Western Australia explained how they had learned how to fix computer problems online: “I’ve learnt a great deal from YouTube”. Others talked about turning to Google, TikTok and, more recently, ChatGPT.

A key question here is the reliability of these sources. This is why students need critical thinking and online literacy skills so they can evaluate what they find online.

‘This is so much money’

Young people in our survey echoed wider community concerns about the rising costs of a university education. As one South Australian man (23) told us:

I was looking at the HECS that came along with [certain courses] and I was like, this is crazy, this is so much money.

One woman (19) explained how the fees had been part of the reason why she didn’t want to go to uni.

Truthfully there was nothing at uni that interested me, any careers that it would be leading me to […] also because university is so expensive, I wouldn’t want to get myself in a HECS debt for the rest of my life.

‘Why don’t I know anyone?’

For those who did go to uni, young people spoke about how they were missing out on the social side of education – partly due to COVID lockdowns, the broader move to hybrid/online learning and changes in campus experiences. As one Queensland 19-year-old told us:

For the past year and a half I kind of just went to class and then went home again and I was like, ‘Why don’t I know anyone? Why do I have no friends?’

While some students reported online study saved time, others told us they found it impersonal and disengaging. As one Victorian (23) told us:

It’s more like I’m learning from my laptop, not by a university I’m paying thousands of dollars to.

Another 23-year-old from NSW said students would complain but learn more if they had face-to-face classes:

[online is] more flexible but it means it’s harder to turn off and on […] more traditional university would be nice.

Some young people are worried

One of the key roles of education is to provide pathways to desirable futures. But 40% of young people told us they were worried about their ability to cope with everyday tasks in the future. Almost 80% told us they thought they would be financially worse off than their parents, up from 53% in 2022.

Education alone can’t address all the challenges facing young people, but we can address some key immediate issues. Our findings suggest young people believe education in Australia needs to be more affordable, practical, social and engaging. To do this we need:

more personalised career counselling and up-to-date labour market information for school leavers and university graduates – so young people have clearer ideas about what study or training can lead to particular jobs and careers

better ways of ensuring online learning enables connections and interactions between students and students and teachers – so learning is not as impersonal and there are more opportunities to learn in person or deliberately social online ways

more investment in campus clubs, student wellbeing programs and peer support so young people have more opportunities to make friends and build networks.

Lucas Walsh, Professor of Education Policy and Practice, Youth Studies, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Wednesday, 12 November 2025

The Roman empire built 300,000 kilometres of roads: new study

At its height, the Roman empire covered some 5 million square kilometres and was home to around 60 million people. This vast territory and huge population were held together via a network of long-distance roads connecting places hundreds and even thousands of kilometres apart.

Compared with a modern road, a Roman road was in many ways over-engineered. Layers of material often extended a metre or two into the ground beneath the surface, and in Italy roads were paved with volcanic rock or limestone.

Roads were also furnished with milestones bearing distance measurements. These would help calculate how long a journey might take or the time for a letter to reach a person elsewhere.

Thanks to these long-lasting archaeological remnants, as well as written records, we can build a picture of what the road network looked like thousands of years ago.

A new, comprehensive map and digital dataset published by a team of researchers led by Tom Brughmans at Aarhus University in Denmark shows almost 300,000 kilometres of roads spanning an area of close to 4 million square kilometres.

The road network

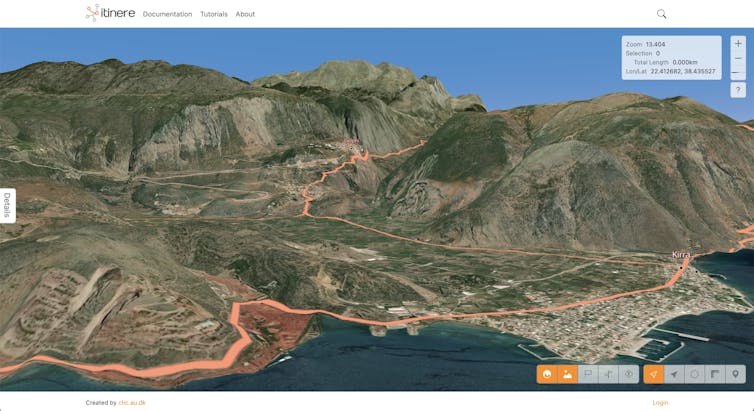

The Itiner-e dataset was pieced together from archaeological and historical records, topographic maps, and satellite imagery.

It represents a substantial 59% increase over the previous mapping of 188,555 kilometres of Roman roads. This is a very significant expansion of our mapped knowledge of ancient infrastructure.

The Via Appia is one of the oldest and most important Roman roads. LivioAndronico2013 / Wikimedia, CC BY

The Via Appia is one of the oldest and most important Roman roads. LivioAndronico2013 / Wikimedia, CC BYAbout one-third of the 14,769 defined road sections in the dataset are classified as long-distance main roads (such as the famous Via Appia that links Rome to southern Italy). The other two-thirds are secondary roads, mostly with no known name.

The researchers have been transparent about the reliability of their data. Only 2.7% of the mapped roads have precisely known locations, while 89.8% are less precisely known and 7.4% represent hypothesised routes based on available evidence.

More realistic roads – but detail still lacking

Itiner-e has improved on past efforts with improved coverage of roads in the Iberian Peninsula, Greece and North Africa, as well as a crucial methodological refinement in how routes are mapped.

Rather than imposing idealised straight lines, the researchers adapted previously proposed routes to fit geographical realities. This means mountain roads can follow winding, practical paths, for example.

Itiner-e includes more realistic terrain-hugging road shapes than some earlier maps. Itiner-e, CC BY

Itiner-e includes more realistic terrain-hugging road shapes than some earlier maps. Itiner-e, CC BYAlthough there is a considerable increase in the data for Roman roads in this mapping, it does not include all the available data for the existence of Roman roads. Looking at the hinterland of Rome, for example, I found great attention to the major roads and secondary roads but no attempt to map the smaller local networks of roads that have come to light in field surveys over the past century.

Itiner-e has great strength as a map of the big picture, but it also points to a need to create localised maps with greater detail. These could use our knowledge of the transport infrastructure of specific cities.

There is much published archaeological evidence that is yet to be incorporated into a digital platform and map to make it available to a wider academic constituency.

Travel time in the Roman empire

Fragment of a Roman milestone erected along the road Via Nova in Jordan. Adam Pažout / Itiner-e, CC BY

Fragment of a Roman milestone erected along the road Via Nova in Jordan. Adam Pažout / Itiner-e, CC BYItiner-e’s map also incorporates key elements from Stanford University’s Orbis interface, which calculates the time it would have taken to travel from point A to B in the ancient world.

The basis for travel by road is assumed to have been humans walking (4km per hour), ox carts (2km per hour), pack animals (4.5km per hour) and horse courier (6km per hour).

This is fine, but it leaves out mule-drawn carriages, which were the major form of passenger travel. Mules have greater strength and endurance than horses, and became the preferred motive power in the Roman empire.

What next?

Itiner-e provides a new means to investigate Roman transportation. We can relate the map to the presence of known cities, and begin to understand the nature of the transport network in supporting the lives of the people who lived in them.

This opens new avenues of inquiry as well. With the network of roads defined, we might be able to estimate the number of animals such as mules, donkeys, oxen and horses required to support a system of communication.

For example, how many journeys were required to communicate the death of an emperor (often not in Rome but in one of the provinces) to all parts of the empire?

Some inscriptions refer to specifically dated renewal of sections of the network of roads, due to the collapse of bridges and so on. It may be possible to investigate the effect of such a collapse of a section of the road network using Itiner-e.

These and many other questions remain to be answered.![]()

Ray Laurence, Professor of Ancient History, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Wednesday, 15 October 2025

Lack of fibre is putting the brakes on UK’s data centre expansion, says study

Thursday, 9 October 2025

The Ganges River is drying faster than ever – here’s what it means for the region and the world

Mehebub Sahana, University of Manchester

The Ganges, a lifeline for hundreds of millions across South Asia, is drying at a rate scientists say is unprecedented in recorded history. Climate change, shifting monsoons, relentless extraction and damming are pushing the mighty river towards collapse, with consequences for food, water and livelihoods across the region.

For centuries, the Ganges and its tributaries have sustained one of the world’s most densely populated regions. Stretching from the Himalayas to the Bay of Bengal, the whole river basin supports over 650 million people, a quarter of India’s freshwater, and much of its food and economic value. Yet new research reveals the river’s decline is accelerating beyond anything seen in recorded history.

Stretches of river that once supported year-round navigation are now impassable in summer. Large boats that once travelled the Ganges from Bengal and Bihar through Varanasi and Allahabad now run aground where water once flowed freely. Canals that used to irrigate fields for weeks longer a generation ago now dry up early. Even some wells that protected families for decades are yielding little more than a trickle.

Global climate models have failed to predict the severity of this drying, pointing to something deeply unsettling: human and environmental pressures are combining in ways we don’t yet understand.

Water has been diverted into irrigation canals, groundwater has been pumped for agriculture, and industries have proliferated along the river’s banks. More than a thousand dams and barrages have radically altered the river itself. And as the world warms, the monsoon which feeds the Ganges has grown increasingly erratic. The result is a river system increasingly unable to replenish itself.

Melting glaciers, vanishing rivers

At the river’s source high in the Himalayas, the Gangotri glacier has retreated nearly a kilometre in just two decades. The pattern is repeating across the world’s largest mountain range, as rising temperatures are melting glaciers faster than ever.

Initially, this brings sudden floods from glacial lakes. In the long-run, it means far less water flowing downstream during the dry season.

These glaciers are often termed the “water towers of Asia”. But as those towers shrink, the summer flow of water in the Ganges and its tributaries is dwindling too.

Humans are making things worse

The reckless extraction of groundwater is aggravating the situation. The Ganges-Brahmaputra basin is one of the most rapidly depleting aquifers in the world, with water levels falling by 15–20 millimeters each year. Much of this groundwater is already contaminated with arsenic and fluoride, threatening both human health and agriculture.

The role of human engineering cannot be ignored either. Projects like the Farakka Barrage in India have reduced dry-season flows into Bangladesh, making the land saltier and threatening the Sundarbans, the world’s largest mangrove forest. Decisions to prioritise short-term economic gains have undermined the river’s ecological health.

Across northern Bangladesh and West Bengal, smaller rivers are already drying up in the summer, leaving communities without water for crops or livestock. The disappearance of these smaller tributaries is a harbinger of what may happen on a larger scale if the Ganges itself continues its downward spiral. If nothing changes, experts warn that millions of people across the basin could face severe food shortages within the next few decades.

Saving the Ganges

The need for urgent, coordinated action cannot be overstated. Piecemeal solutions will not be enough. It’s time for a comprehensive rethinking of how the river is managed.

That will mean reducing unsustainable extraction of groundwater so supplies can recharge. It will mean environmental flow requirements to keep enough water in the river for people and ecosystems. And it will require improved climate models that integrate human pressures (irrigation and damming, for example) with monsoon variability to guide water policy.

Transboundary cooperation is also a must. India, Bangladesh and Nepal must do better at sharing data, managing dams, and planning for climate change. International funding and political agreements must treat rivers like the Ganges as global priorities. Above all, governance must be inclusive, so local voices shape river restoration efforts alongside scientists and policymakers.

The Ganges is more than a river. It is a lifeline, a sacred symbol, and a cornerstone of South Asian civilisation. But it is drying faster than ever before, and the consequences of inaction are unthinkable. The time for warnings has passed. We must act now to ensure the Ganges continues to flow – not just for us, but for generations to come.![]()

Mehebub Sahana, Leverhulme Early Career Fellow, Geography, University of Manchester

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Wednesday, 8 October 2025

How safe is your face? The pros and cons of having facial recognition everywhere

Joanne Orlando, Western Sydney University

Walk into a shop, board a plane, log into your bank, or scroll through your social media feed, and chances are you might be asked to scan your face. Facial recognition and other kinds of face-based biometric technology are becoming an increasingly common form of identification.

The technology is promoted as quick, convenient and secure – but at the same time it has raised alarm over privacy violations. For instance, major retailers such as Kmart have been found to have broken the law by using the technology without customer consent.

So are we seeing a dangerous technological overreach or the future of security? And what does it mean for families, especially when even children are expected to prove their identity with nothing more than their face?

The two sides of facial recognition

Facial recognition tech is marketed as the height of seamless convenience.

Nowhere is this clearer than in the travel industry, where airlines such as Qantas tout facial recognition as the key to a smoother journey. Forget fumbling for passports and boarding passes – just scan your face and you’re away.

In contrast, when big retailers such as Kmart and Bunnings were found to be scanning customers’ faces without permission, regulators stepped in and the backlash was swift. Here, the same technology is not seen as a convenience but as a serious breach of trust.

Things get even murkier when it comes to children. Due to new government legislation, social media platforms may well introduce face-based age verification technology, framing it as a way to keep kids safe online.

At the same time, schools are trialling facial recognition for everything from classroom entry to paying in the cafeteria.

Yet concerns about data misuse remain. In one incident, Microsoft was accused of mishandling children’s biometric data.

For children, facial recognition is quietly becoming the default, despite very real risks.

A face is forever

Facial recognition technology works by mapping someone’s unique features and comparing them against a database of stored faces. Unlike passive CCTV cameras, it doesn’t just record, it actively identifies and categorises people.

This may feel similar to earlier identity technologies. Think of the check-in QR code systems that quickly sprung up at shops, cafes and airports during the COVID pandemic.

Facial recognition may be on a similar path of rapid adoption. However, there is a crucial difference: where a QR code can be removed or an account deleted, your face cannot.

Why these developments matter

Permanence is a big issue for facial recognition. Once your – or your child’s – facial scan is stored, it can stay in a database forever.

If the database is hacked, that identity is compromised. In a world where banks and tech platforms may increasingly rely on facial recognition for access, the stakes are very high.

What’s more, the technology is not foolproof. Mis-identifying people is a real problem.

Age-estimating systems are also often inaccurate. One 17-year-old might easily be classified as a child, while another passes as an adult. This may restrict their access to information or place them in the wrong digital space.

A lifetime of consequences

These risks aren’t just hypothetical. They already affect lives. Imagine being wrongly placed on a watchlist because of a facial recognition error, leading to delays and interrogations every time you travel.

Or consider how stolen facial data could be used for identity theft, with perpetrators gaining access to accounts and services.

In the future, your face could even influence insurance or loan approvals, with algorithms drawing conclusions about your health or reliability based on photo or video.

Facial recognition does have some clear benefits, such as helping law enforcement identify suspects quickly in crowded spaces and providing convenient access to secure areas.

But for children, the risks of misuse and error stretch across a lifetime.

So, good or bad?

As it stands, facial recognition would seem to carry more risks than rewards. In a world rife with scams and hacks, we can replace a stolen passport or drivers’ licence, but we can’t change our face.

The question we need to answer is where we draw the line between reckless implementation and mandatory use. Are we prepared to accept the consequences of the rapid adoption of this technology?

Security and convenience are important, but they are not the only values at stake. Until robust, enforceable rules around safety, privacy and fairness are firmly established, we should proceed with caution.

So next time you’re asked to scan your face, don’t just accept it blindly. Ask: why is this necessary? And do the benefits truly outweigh the risks – for me, and for everyone else involved?![]()

Joanne Orlando, Researcher, Digital Wellbeing, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Monday, 6 October 2025

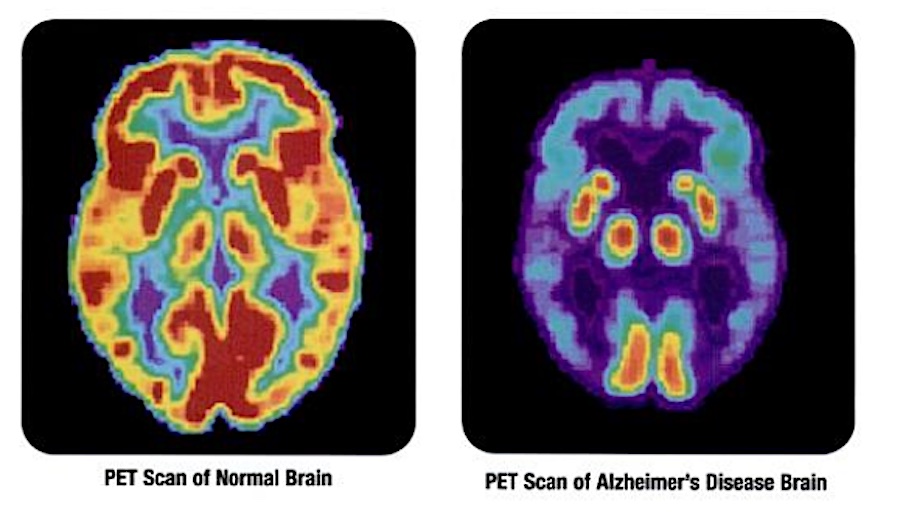

Tiny Protein Confirmed to Dismantle the Toxic Clumps Linked to Alzheimer’s Disease

Monday, 15 September 2025

1 in 4 people globally still lack access to safe drinking water, report finds

.jpg)

- Despite gains since 2015, 1 in 4 – or 2.1 billion people globally – still lack access to safely managed drinking water*, including 106 million who drink directly from untreated surface sources.

- 3.4 billion people still lack safely managed sanitation, including 354 million who practice open defecation.

- 1.7 billion people still lack basic hygiene services at home, including 611 million without access to any facilities.

- People in least developed countries are more than twice as likely as people in other countries to lack basic drinking water and sanitation services, and more than three times as likely to lack basic hygiene.

- In fragile contexts**, safely managed drinking water coverage is 38 percentage points lower than in other countries, highlighting stark inequalities.

- While there have been improvements for people living in rural areas, they still lag behind. Safely managed drinking water coverage rose from 50 per cent to 60 per cent between 2015 and 2024, and basic hygiene coverage from 52 per cent to 71 per cent. In contrast, drinking water and hygiene coverage in urban areas has stagnated.

- Data from 70 countries show that while most women and adolescent girls have menstrual materials and a private place to change, many lack sufficient materials to change as often as needed.

- Adolescent girls aged 15–19 are less likely than adult women to participate in activities during menstruation, such as school, work and social pastimes.

- In most countries with available data, women and girls are primarily responsible for water collection, with many in sub-Saharan Africa and Central and Southern Asia spending more than 30 minutes per day collecting water.

- As we approach the last five years of the Sustainable Development Goals period, achieving the 2030 targets for ending open defecation and universal access to basic water, sanitation and hygiene services will require acceleration, while universal coverage of safely managed services in this area appears increasingly out of reach.

Saturday, 14 June 2025

Above-average monsoon drives rural demand for Indian automobile sector: HSBC

Tuesday, 27 May 2025

Lipolysis more effective in women than men: Study

New Delhi, (IANS) A team of researchers has said that lipolysis is more effective in women than in men, which could partly explain why women are less likely to develop metabolic complications than men, despite having more body fat.

Tuesday, 13 May 2025

Australia and North America have long fought fires together – but new research reveals that has to change

Climate change is lengthening fire seasons across much of the world. This means the potential for wildfires at any time of the year, in both hemispheres, is increasing.

That poses a problem. Australia regularly shares firefighting resources with the United States and Canada. But these agreements rest on the principle that when North America needs these personnel and aircraft, Australia doesn’t, and vice versa. Climate change means this assumption no longer holds.

The devastating Los Angeles wildfires in January, the United States winter, show how this principle is being tested. The US reportedly declined Australia’s public offer of assistance because Australia was in the midst of its traditional summer fire season. Instead, the US sought help from Canada and Mexico.

But to what extent do fire seasons in Australia and North America actually overlap? Our new research examined this question. We found an alarming increase in the overlap of the fire seasons, suggesting both regions must invest far more in their own permanent firefighting capacity.

What we did

We investigated fire weather seasons – that is, the times of the year when atmospheric conditions such as temperature, humidity, rainfall and wind speed are conducive to fire.

The central question we asked was: how many days each year do fire weather seasons in Australia and North America overlap?

To determine this, we calculated the length of the fire weather seasons in the two regions in each year, and the number of days when the seasons occur at the same time. We then analysed reconstructed historical weather data to assess fire-season overlap for the past 45 years. We also analysed climate model data to assess changes out to the end of this century.

And the result? On average, fire weather occurs in both regions simultaneously for about seven weeks each year. The greatest risk of overlap occurs in the Australian spring – when Australia’s season is beginning and North America’s is ending.

The overlap has increased by an average of about one day per year since 1979. This might not sound like much. But it translates to nearly a month of extra overlap compared to the 1980s and 1990s.

The increase is driven by eastern Australia, where the fire weather season has lengthened at nearly twice the rate of western North America. More research is needed to determine why this is happening.

Longer, hotter, drier

Alarmingly, as climate change worsens and the atmosphere dries and heats, the overlap is projected to increase.

The extent of the overlap varied depending on which of the four climate models we used. Assuming an emissions scenario where global greenhouse gas emissions begin to stabilise, the models projected an increase in the overlap of between four and 29 days a year.

What’s behind these differences? We think it’s rainfall. The models project quite different rainfall trends over Australia. Those projecting a dry future also project large increases in overlapping fire weather. What happens to ours and North America’s rainfall in the future will have a large bearing on how fire seasons might change.

While climate change will dominate the trend towards longer overlapping fire seasons, El Niño and La Niña may also play a role.

These climate drivers involve fluctuations every few years in sea surface temperature and air pressure in part of the Pacific Ocean. An El Niño event is associated with a higher risk of fire in Australia. A La Niña makes longer fire weather seasons more likely in North America.

There’s another complication. When an El Niño occurs in the Central Pacific region, this increases the chance of overlap in fire seasons of North America and Australia. We think that’s because this type of El Niño is especially associated with dry conditions in Australia’s southeast, which can fuel fires.

But how El Niño and La Niña will affect fire weather in future is unclear. What’s abundantly clear is that global warming will lead to more overlap in fire seasons between Australia and North America – and changes in Australia’s climate are largely driving this trend.

Looking ahead

Firefighters and their aircraft are likely to keep crossing the Pacific during fire emergencies.

But it’s not difficult to imagine, for example, simultaneous fires occurring in multiple Australian states during spring, before any scheduled arrival of aircraft from the US or Canada. If North America is experiencing late fires that year and cannot spare resources, Australia’s capabilities may be exceeded.

Likewise, even though California has the largest civil aerial firefighting fleet in the world, the recent Los Angeles fires highlighted its reliance on leased equipment.

Fire agencies are becoming increasingly aware of this clash. And a royal commission after the 2019–20 Black Summer fires recommended Australia develop its own fleet of firefighting aircraft.

Long, severe fire seasons such as Black Summer prompted an expansion of Australia’s permanent aerial firefighting fleet, but more is needed.

As climate change accelerates, proactive fire management, such as prescribed burning, is also important to reduce the risk of uncontrolled fire outbreaks.![]()

Doug Richardson, Research Associate in Climate Science, UNSW Sydney and Andreia Filipa Silva Ribeiro, Climate Researcher, Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research-UFZ

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Sunday, 20 April 2025

Earth’s oceans once turned green – and they could change again

Nearly three fourths of Earth is covered by oceans, making the planet look like a pale blue dot from space. But Japanese researchers have made a compelling case that Earth’s oceans were once green, in a study published in Nature.

The reason Earth’s oceans may have looked different in the ancient past is to do with their chemistry and the evolution of photosynthesis. As a geology undergraduate student, I was taught about the importance of a type of rock deposit known as the banded iron formation in recording the planet’s history.

Banded iron formations were deposited in the Archean and Paleoproterozoic eons, roughly between 3.8 and 1.8 billion years ago. Life back then was confined to one cell organisms in the oceans. The continents were a barren landscape of grey, brown and black rocks and sediments.

Rain falling on continental rocks dissolved iron which was then carried to the oceans by rivers. Other sources of iron were volcanoes on the ocean floor. This iron will become important later.

The Archaean eon was a time when Earth’s atmosphere and ocean were devoid of gaseous oxygen, but also when the first organisms to generate energy from sunlight evolved. These organisms used anaerobic photosynthesis, meaning they can do photosynthesis in the absence of oxygen.

It triggered important changes as a byproduct of anaerobic photosynthesis is oxygen gas. Oxygen gas bound to iron in seawater. Oxygen only existed as a gas in the atmosphere once the seawater iron could neutralise no more oxygen.

Eventually, early photosynthesis led to the “great oxidation event”, a major ecological turning point that made complex life on Earth possible. It marked the transition from a largely oxygen free Earth to one with large amounts of oxygen in the ocean and atmosphere.

The “bands” of different colours in banded iron formations record this shift with an alternation between deposits of iron deposited in the absence of oxygen and red oxidised iron.

The case for green oceans

The recent paper’s case for green oceans in the Archaean eon starts with an observation: waters around the Japanese volcanic island of Iwo Jima have a greenish hue linked to a form of oxidised iron - Fe(III). Blue-green algae thrive in the green waters surrounding the island.

Despite their name, blue-green algae are primitive bacteria and not true algae. In the Archaean eon, the ancestors of modern blue-green algae evolved alongside other bacteria that use ferrous iron instead of water as the source of electrons for photosynthesis. This points to high levels of iron in the ocean.

Photosynthetic organisms use pigments (mostly chlorophyll) in their cells to transform CO₂ into sugars using the energy of the sun. Chlorophyll gives plants their green colour. Blue-green algae are peculiar because they carry the common chlorophyll pigment, but also a second pigment called phycoerythrobilin (PEB).

In their paper, the researchers found that genetically engineered modern blue-green algae with PEB grow better in green waters. Although chlorophyll is great for photosynthesis in the spectra of light visible to us, PEB seems to be superior in green-light conditions.

Before the rise of photosynthesis and oxygen, Earth’s oceans contained dissolved reduced iron (iron deposited in the absence of oxygen). Oxygen released by the rise of photosynthesis in the Archean eon then led to oxidised iron in seawater. The paper’s computer simulations also found oxygen released by early photosynthesis led to a high enough concentration of oxidised iron particles to turn the surface water green.

Once all iron in the ocean was oxidised, free oxygen (0₂) existed in Earth’s oceans and atmosphere. So a major implication of the study is that pale-green dot worlds viewed from space are good candidates planets to harbour early photosynthetic life.

The changes in ocean chemistry were gradual. The Archaean period lasted 1.5 billion years. This is more than half of Earth’s history. By comparison, the entire history of the rise and evolution of complex life represents about an eighth of Earth’s history.

Almost certainly, the colour of the oceans changed gradually during this period and potentially oscillated. This could explain why blue-green algae evolved both forms of photosynthetic pigments. Chlorophyll is best for white light which is the type of sunlight we have today. Taking advantage of green and white light would have been an evolutionary advantage.

Could oceans change colour again?

The lesson from the recent Japanese paper is that the colour of our oceans are linked to water chemistry and the influence of life. We can imagine different ocean colours without borrowing too much from science fiction.

Purple oceans would be possible on Earth if the levels of sulphur were high. This could be linked to intense volcanic activity and low oxygen content in the atmosphere, which would lead to the dominance of purple sulphur bacteria.

Red oceans are also theoretically possible under intense tropical climates when red oxidised iron forms from the decay of rocks on the land and is carried to the oceans by rivers or winds. Or if a type of algae linked to “red tides” came to dominate the surface oceans.

These red algae are common in areas with intense concentration of fertiliser such as nitrogen. In the modern oceans, this tends to happen in coastline close to sewers.

As our sun ages, it will first become brighter leading to increased surface evaporation and intense UV light. This may favour purple sulphur bacteria living in deep waters without oxygen.

It will lead to more purple, brown, or green hues in coastal or stratified areas, with less deep blue colour in water as phytoplankton decline. Eventually, oceans will evaporate completely as the sun expands to encompass the orbit of Earth.

At geological timescales nothing is permanent and changes in the colour of our oceans are therefore inevitable.![]()

Cédric M. John, Professor and Head of Data Science for the Environment and Sustainability, Queen Mary University of London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tuesday, 17 December 2024

New research shows how long, hard and often you need to stretch to improve your flexibility

Can you reach down and touch your toes without bending your knees? Can you reach both arms overhead? If these sound like a struggle, you may be lacking flexibility.

Flexibility is the ability to move a joint to through its full range of motion. It helps you perform most sporting activities and may prevent muscle injuries. And because most daily activities require a certain amount of flexibility (like bending down or twisting), it will help you maintain functional independence as you age.

Although there are many types of stretching, static stretching is the most common. It involves positioning a joint to lengthen the muscles and holding still for a set period – usually between 15 and 60 seconds. An example would be to stand in front of a chair, placing one foot on the chair and straightening your knee to stretch your hamstrings.

Static stretching is widely used to improve flexibility. But there are no clear recommendations on the optimal amount required. Our new research examined how long, how hard and how often you need to stretch to improve your flexibility – it’s probably less than you expect.

Assessing the data

Our research team spent the past year gathering data from hundreds of studies on thousands of adults from around the world. We looked at 189 studies of more than 6,500 adults.

The studies compared the effects of a single session or multiple sessions of static stretching on one or more flexibility outcomes, compared to those who didn’t stretch.

How long?

We found holding a stretch for around four minutes (cumulatively) in a single session is optimal for an immediate improvement in flexibility. Any longer and you don’t appear to get any more improvement.

For permanent improvements in flexibility, it looks like you need to stretch a muscle for longer – around ten minutes per week for the biggest improvement. But this doesn’t need to occur all at once.

How hard?

You can think of stretching as being hard, when you stretch into pain, or easy, when the stretch you feel isn’t uncomfortable.

The good news is how hard you stretch doesn’t seem to matter – both hard (stretching to the point of discomfort or pain) and easy stretching (stretching below the point of discomfort) equally improve flexibility.

How often?

If you are looking to improve your flexibility, it doesn’t matter how often you stretch each week. What is important is that you aim for up to ten minutes per week for each muscle that you stretch.

So, for example, you could stretch each muscle for a little more than one minute a day, or five minutes twice a week.

The amount of time you should spend stretching will ultimately depend on how many muscles you need to stretch. If you are less flexible, you will likely need to dedicate more time, given you’ll have more “tight” muscles to stretch compared to someone more flexible.

Can everyone improve their flexibility?

Encouragingly, it doesn’t matter what muscle you stretch, how old you are, your sex, or whether you are a couch potato or an elite athlete – everyone can improve their flexibility.

Static stretching can be done anywhere and at any time. And you don’t need any equipment. You can stretch while watching your favourite TV show, when in the office, or after walking the dog to help you relax. It’s a great way to start and end your day.

Although the exact stretches needed will depend on which muscles are “tight”, examples of some very common stretches include:

- placing one foot upon on bench and leaning forward at the waist while keeping your knee straight to stretch your hamstrings

- bending your knee and holding your ankle against your buttock to stretch your quadriceps muscles

- reaching one arm while bending your elbow to stretch your triceps muscles.

However, the best advice is to visit a qualified health professional, such as a physiotherapist or exercise physiologist, who can perform an assessment and prescribe you a list of stretches specific to your individual needs.

As you can see, it really isn’t too much of a stretch to become more flexible.![]()

Lewis Ingram, Lecturer in Physiotherapy, University of South Australia; Grant R. Tomkinson, Professor of Exercise and Sport Science, University of South Australia, and Hunter Bennett, Lecturer in Exercise Science, University of South Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.