Friday, 23 January 2026

Human heart regrows muscle cells after heart attack: Study

Monday, 6 October 2025

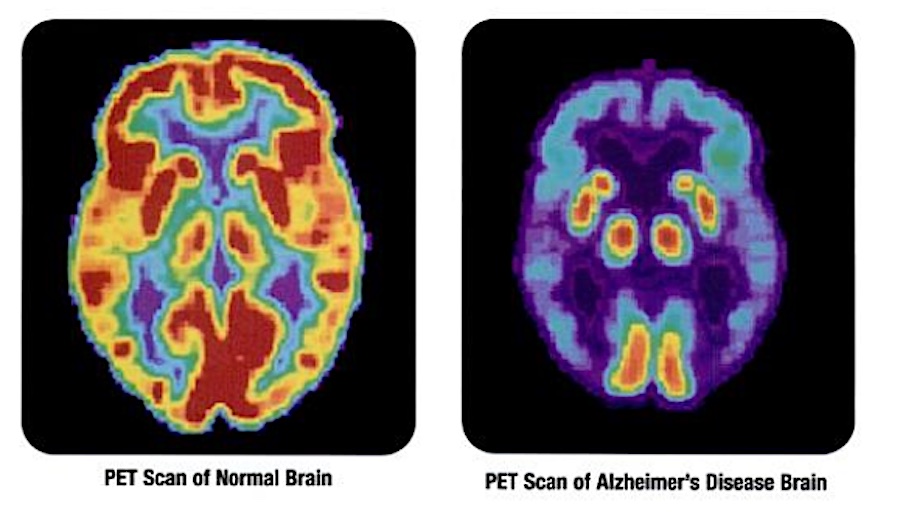

Tiny Protein Confirmed to Dismantle the Toxic Clumps Linked to Alzheimer’s Disease

Friday, 26 July 2024

Researchers link hot weather with increased headaches for people with migraines

Sunday, 24 March 2024

Can animals give birth to twins?

We are faculty members at Mississippi State University College of Veterinary Medicine. We’ve been present for the births of many puppies and kittens over the years – and the animal moms almost always deliver multiples.

But are all those animal siblings who share the same birthday twins?

Twins are two peas in a pod

Twins are defined as two offspring from the same pregnancy.

They can be identical, which means a single sperm fertilized a single egg that divided into two separate cells that went on to develop into two identical babies. They share the same DNA, and that’s why the two twins are essentially indistinguishable from each other.

Twins can also be fraternal. That’s the outcome when two separate eggs are fertilized individually at the same time. Each twin has its own set of genes from the mother and the father. One can be male and one can be female. Fraternal twins are basically as similar as any set of siblings.

Approximately 3% of human pregnancies in the United States produce twins. Most of those are fraternal – approximately one out of every three pairs of twins is identical.

Multiple babies from one animal mom

Each kind of animal has its own standard number of offspring per birth. People tend to know the most about domesticated species that are kept as pets or farm animals.

One study that surveyed the size of over 10,000 litters among purebred dogs found that the average number of puppies varied by the size of the dog breed. Miniature breed dogs – like chihuahuas and toy poodles, generally weighing less than 10 pounds (4.5 kilograms) – averaged 3.5 puppies per litter. Giant breed dogs – like mastiffs and Great Danes, typically over 100 pounds (45 kilograms) – averaged more than seven puppies per litter.

When a litter of dogs, for instance, consists of only two offspring, people tend to refer to the two puppies as twins. Twins are the most common pregnancy outcome in goats, though mom goats can give birth to a single-born kid or larger litters, too. Sheep frequently have twins, but single-born lambs are more common.

Horses, which are pregnant for 11 to 12 months, and cows, which are pregnant for nine to 10 months, tend to have just one foal or calf at a time – but twins may occur. Veterinarians and ranchers have long believed that it would be financially beneficial to encourage the conception of twins in dairy and beef cattle. Basically the farmer would get two calves for the price of one pregnancy.

But twins in cattle may result in birth complications for the cow and undersized calves with reduced survival rates. Similar risks come with twin pregnancies in horses, which tend to lead to both pregnancy complications that may harm the mare and the birth of weak foals.

DNA holds the answer to what kind of twins

So plenty of animals can give birth to twins. A more complicated question is whether two animal babies born together are identical or fraternal twins.

And reproduction is different in various animals. For instance, nine-banded armadillos normally give birth to identical quadruplets. After a mother armadillo releases an egg and it becomes fertilized, it splits into four separate identical cells that develop into identical pups. Its relative, the seven-banded armadillo, can give birth to anywhere from seven to nine identical pups at one time.

There’s still a lot that scientists aren’t sure about when it comes to twins in other species. Since DNA testing is not commonly performed in animals, no one really knows how often identical twins are born. It’s possible – maybe even likely – that identical twins may have been born in some species without anyone’s ever knowing.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.![]()

Michael Jaffe, Associate Professor of Small Animal Surgery, Mississippi State University and Tracy Jaffe, Assistant Clinical Professor of Veterinary Medicine, Mississippi State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Monday, 18 March 2024

Multivitamins may help slow memory loss in older adults, study shows

Monday, 9 October 2023

Women aren’t failing at science

Female scientists are often more productive than their male colleagues but much less likely to be recognised for their work. Argonne National Laboratory/Wikimedia, CC BY-SA

Lorena Rivera León, United Nations University

Female scientists are often more productive than their male colleagues but much less likely to be recognised for their work. Argonne National Laboratory/Wikimedia, CC BY-SA

Lorena Rivera León, United Nations UniversityFemale research scientists are more productive than their male colleagues, though they are widely perceived as being less so. Women are also rewarded less for their scientific achievements.

That’s according to my team’s study for United Nations University - Merit on gender inequality in scientific research in Mexico, published as a working paper in December 2016.

The study, part of the project “Science, Technology and Innovation Gender Gaps and their Economic Costs in Latin America and the Caribbean”, was financed by the Gender and Diversity Fund of the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB).

The ‘productivity puzzle’

The study, which looked at women’s status in 42 public universities and 18 public research centres, some managed by Mexico’s National Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT), focused on a question that has been widely investigated: why are women in science less productive than men, in almost all academic disciplines and regardless of the productivity measure used?

The existence of this “productivity puzzle” is well documented, from South Africa to Italy, but few studies have sought to identify its possible causes.

Our findings demonstrate that, in Mexico at least, the premise of the productivity puzzle is false, when we control for factors such as promotion to senior academic ranks and selectivity.

Using an econometric modelling approach, including several macro simulations to understand the economic costs of gender gaps to the Mexican academic system, our study focused on researchers within Mexico’s National System of Researchers.

A presentation on Mexican government funding for scientific investment. How many women can you count? Government of Aguascalientes/flickr, CC BY-SA

A presentation on Mexican government funding for scientific investment. How many women can you count? Government of Aguascalientes/flickr, CC BY-SAAdditionally, despite the common belief that maternity leaves make women less productive in key periods of their careers, female researchers in fact have only between 5% to 6% more non-productive years than males. At senior levels, the difference drops to 1%.

Nonetheless, in the universities and research centres we studied, Mexican women face considerable barriers to success. At public research centres, women are 35% less likely to be promoted, and 89% of senior ranks were filled by men in 2013, though women comprised 24% of research staff and 33% at non-senior levels. Public universities do slightly better (but not well): female researchers there are 22% less likely to be promoted than men.

Overall, 89% of all female academics in our sample never reached senior levels in the period studied (2002 to 2013).

In some ways this data should not be surprising. Mexico ranks 66th out of 144 in the World Economic Forum’s 2016 Global Gender Gap Report and a 2015 report by the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) showed that among OECD countries Mexico has the widest overall gender gap in labour participation rates.

Some efforts are being made to improve gender equality in research. In 2013 Mexico amended four articles of its Science and Technology Law to promote gender equality in those fields, adding provisions to promote gender-balanced participation in publicly funded higher education institutions and collect gender-specific data to measure the impact of gender on science and technology policies.

Several CONACYT research centres have launched initiatives to promote gender equality among staff, but many of these internal programmes are limited to anti-discrimination and sexual harassment training.

More aggressive programmes include: the Research Centre on Social Anthopology’s graduate scholarship programme, in collaboration with CONACYT and the National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples, to promote higher education and training among indigenous women; and policies to increase women’s participation in higher academic ranks and management at the CIATEQ technological institute, which also gives childcare subsidies to female staff.

But such examples are rare. Overall, women hoping to succeed in Mexican academia must work harder and produce more than their male colleagues to be even considered for promotion to senior ranks.

This persistent inequality has implications not just for women but for the country’s scientific production: if Mexico were to eliminate gender inequality in promotions, the national academic system would see 17% to 20% more peer-reviewed articles published.

A global glass ceiling

Mexico is not alone. Our previous research in France and South Africa, using the same econometric model, found that gender inequalities there also prevent women scientists from being promoted to higher academic ranks.

Examining French physicists working in the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) and in French public universities, we learned that female physicists in CNRS are as productive as their male colleagues or more so. Yet they are 6.3% less likely to be promoted within CNRS and 16.3% within universities. This is notable in a country that ranks 17th in the world in gender equality, according to the World Economic Forum.

Black women face more barriers to advancement in the sciences than white women. World Bank Photo Collection/flickr, CC BY-NC-SA

Black women face more barriers to advancement in the sciences than white women. World Bank Photo Collection/flickr, CC BY-NC-SAIn Uruguay the same IDB gender gaps project identified a glass ceiling as well. There women are underrepresented in the highest academic ranks and have a 7.1% less probability than men of being promoted to senior levels.

Moreover, from Mexico and Uruguay to France and South Africa, a vicious cycle between promotion and productivity is at play: difficulties in getting promoted reduce the prestige, influence and resources available to women. In turn, those factors can lead to lower productivity, which decreases their chances of promotion.

This two-way causality creates a source of endogeneity biases when including seniority as a variable to explain productivity in an econometric model. Only when we control for this, as well as for a selectivity bias (that is, publishing occurrence), do we find that female researchers are more productive than their male counterparts. Without these corrections, a gender productivity gap of 10% to 21% appears in favour of men.

The view that women are failing at science is commonly held, but evidence shows that, across the world, it’s science that’s failing women. Action must be taken to ensure that female researchers are treated fairly, recognised for their work, and promoted when they’ve earned it.![]()

Lorena Rivera León, Economist and Research Fellow, United Nations University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tuesday, 19 September 2023

Ever wonder how your body turns food into fuel? We tracked atoms to find out

Monday, 7 December 2020

'How airflow inside car may affect COVID-19 transmission risk decoded'

Sunday, 16 August 2020

'Blood test may tell if you are at risk of severe COVID-19 infection'

Thursday, 6 August 2020

India's Covid testing rate is low, says WHO Chief Scientist

Underlining the importance of adequate testing for COVID-19, World Health Organisation's (WHO) Chief Scientist, Dr Soumya Swaminathan, on Tuesday said that India's testing rate is low, compared to other countries which have done well in combating the pandemic.

Tuesday, 28 July 2020

Scientists discover potential sustainable energy technology for the household refrigerator

- While many advancements have been in improving its efficiency, the refrigerator still consumes considerable amounts of energy each year.

- "Energy efficiency of a normal refrigerator is affected by the heat-insulating property of the thermal barriers of the freezer. This is due to its low inner temperature," explained Jingyu Cao at the University of Science and Technology of China. "There is a significant difference in temperature between the freezer of a traditional refrigerator and ambient air temperature and the normal thermal barrier of the freezer causes considerable cold loss."

- Cao and his team hypothesized that using part of the cold loss to cool the fresh food compartment could be a promising solution in improving the efficiency of the refrigerator. They describe their findings in the Journal of Renewable and Sustainable Energy, from AIP Publishing.

- "The evaporating temperature of the refrigeration cycle depends only on the freezer temperature and appropriate reduction of the evaporator area in the fresh food compartment will not decrease the overall efficiency," explained Cao.

- "Most families need one or two refrigerators and they are always on 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. That wastes a lot of energy. Even if we can save a little energy, that helps the human race be more energy-efficient," said Cao.

- Cao and his team are not the first scientists to attempt to improve the efficiency of household refrigeration. Extensive experiments by many different scientists have looked at various parts of the refrigerator to improve energy consumption, but a definitive solution has not yet been found. In Cao's study, a novel refrigerator with a loop thermosyphon is put forward to decrease the heat transfer between the freezer and ambient air.

- "One of the surprises was how much energy we saved. The energy-saving ratio of the improved walls got close to 30 per cent — more than we had expected. This technology even works in hot climates like the desert."

- Although Cao's study is currently based on theoretical calculation, the results are promising. "It has great potential to be popularized as a sustainable energy technology or applied in the renewable energy field, considering its significant energy-saving effect, simple structure and low cost," said Cao. Source: https://www.domain-b.com

Saturday, 25 July 2020

Vaccines could reduce antibiotic use in children

- Pneumococcal and rotavirus vaccines, designed to protect against acute respiratory illness (ARI) and diarrhoea, have the potential to reduce episodes of antibiotic use in children in low- and middle-income countries, an international research team has found1.

- The researchers say the study supports ptioritisinf childhood vaccines as part of a global strategy to combat antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

- Previous studies have predicted that vaccines might help avert AMR by preventing infections that are treated with antibiotics. Few studies, however, explored the effects of vaccines on antibiotic use.

- To find out, the scientists, including an Indian researcher from the Centre for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy in New Delhi, estimated the impact of the pneumococcal and rotavirus vaccines on antibiotic use in children under five years of age. They analysed data from household surveys covering 944,173 children across 77 countries from 2006 to 2018.

- The researchers found that both vaccines reduce antibiotic consumption among children. Vaccinated children had lower chances of getting antibiotic treatment for respiratory and diarrhoeal infections compared with unvaccinated ones, they report.

- The vaccines, the researchers estimate, prevent more than 37 million episodes of antibiotic use among children every year. In the absence of these vaccines, the pathogens would cause more than 100 million episodes of antibiotic-treated respiratory illness and diarrhoea.

- The researchers say that such vaccines may even prevent an additional 40 million episodes of antibiotic-treated illnesses.

- References: 1. Lewnard, J. A. et al. Childhood vaccines and antibiotic use in low- and middle-income countries. Nature (2020) doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2238-4 Source: https://www.natureasia.com/

Monday, 13 July 2020

Shifting alpine vegetation in Kashmir Himalayas

- The richness of species in the alpine mountain summits of Kashmir Himalayas is a good indicator of vegetation shifting upwards, according to new research1. This supports earlier theories that rise in temperature and reduced precipitation may be triggering the upward migration of alpine species in the Himalayas.

- Scientists conducting the study in the Apharwat mountain in Gulmarg area of Jammu & Kashmir say understanding the relationship between biodiversity and climate change is critical for future forecasts on vegetation patterns. Himalayas, with the world’s highest mountain peaks harbouring global biodiversity hotspots of alpine flora, are one of the most climate warming-sensitive regions.

- Earlier research2 suggested that warming could change alpine vegetation through the phenomenon of thermophilization – the increased dominance of warm-adapted species and the loss of cold-adapted species.

- Researcher Anzar Khuru from the University of Kashmir in Srinagar says that in these warm conditions, plant species specially adapted to cold habitats move upwards or could go extinct locally.

- The researchers set out to fill the knowledge gaps due to limited research on warming-induced biodiversity changes in a rapidly warming Himalaya. “We observed an increase in species richness during the re-sampling of the alpine summits.” This is an alarming signal of new thermophilic species establishing themselves at higher summits, and the likelihood of local species being competitively displaced, Khuru says.

- The researchers call for more investigation as biodiversity change in the alpine summit ecosystems can have widespread consequences for ecosystem functioning.

- References:

- 1. Hamid, M. et al. Early evidence of shifts in alpine summit vegetation: A case study from Kashmir Himalaya. Plant Sci. (2020) doi:10.3389/fpls.2020.00421

- 2. Pauli, H. et al. Recent plant diversity changes on Europe’s mountain summits. Science 336, 353-355 (2012) doi:10.1126/science.1219033 Source: https://www.natureasia.com/

Saturday, 28 April 2018

Scientists discover greener way of making plastics

- Plastics have crept into our everday life so unobtrusively, that one cannot imagine where they cannot be found from food packagings to wearable products and everyday electronics. But, plastics in daily life come at a pricce; they release carbon dioxide in the environment.

- Now, researchers at the Energy Safety Research Institute (ESRI) at Swansea University in the UK have found a way of converting waste carbon dioxide into a molecule that forms the basis of making plastics.

- The potential of using global ethylene derived from carbon dioxide (CO2) is huge, utilising half a billion tonnes of the carbon emitted each year and offsetting global carbon emissions.

- Dr Enrico Andreoli, who heads the CO2 utilisation group at ESRI, says, "Carbon dioxide is responsible for much of the damage caused to our environment.

- Considerable research focuses on capturing and storing harmful carbon dioxide emissions. But an alternative to expensive long-term storage is to use the captured CO2 as a resource to make useful materials.

- That's why rfesearchers at Swansea have converted waste carbon dioxide into a molecule called ethylene.

- Ethylene is one of the most widely used molecules in the chemical industry and is the starting material in the manufacture of detergents, synthetic lubricants, and the vast majority of plastics like polyethylene, polystyrene, and polyvinyl chloride essential to modern society."

- Dr Andreoli says, "Currently, ethylene is produced at a very high temperature by steam from oils cracking. We need to find alternative ways of producing it before we run out of oil."

- The CO2 utilisation group uses CO2, water and green electricity to generate a sustainable ethylene at room temperature. Central to this process is a new catalyst — a material engineered to speed up the formation of ethylene. Dr Andreoli explains, "We have demonstrated that copper and a polyamide additive can be combined to make an excellent catalyst for CO2 utilisation. The polyamide doubles the efficiency of ethylene formation achieving one of the highest rates of conversion ever recorded in standard bicarbonate water solutions."

- The CO2 utilisation group worked in collaboration with the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and the European Synchrotron Research Facility in Grenoble in the formation of the catalyst.

- Dr Andreoli concludes, "The potential of using CO2 for making everyday materials is huge, and would certainly benefit large-scale producers. We are now actively looking for industrial partners interested in helping take this globally-relevant, 21st century technology forward."Source: https://www.domain-b.com/

Monday, 4 May 2015

Japan honours C N R Rao with its highest civilian award

The Japanese government will confer the `Order of the Rising Sun, Gold and Silver Star', Japan's highest civilian award that is conferred on academicians, politicians and military officers, on Professor Chintamani Nagesa Ramachandra Rao (CNR Rao), eminent Indian scientist. The award is being given for his ''contribution to promoting academic interchange and mutual understanding in science and technology between Japan and India'', an official release said. Rao is one of the world's foremost solid state and materials chemists and has been bestowed with about 70 honorary doctorates and received the highest civilian award of India, Bharat Ratna. Professor CNR Rao is a National Research Professor, Linus Pauling Research Professor and honorary president of the Jawaharlal Nehru Centre for Advanced Scientific Research, Bengaluru, an autonomous institution supported by the ministry of science and technology, Government of India. Professor Rao had made substantial contributions to the development of science in India and the Third World. Born on 30 June 1934, has authored around 1,500 research papers and 45 scientific books. In 2014 the became the third scientist C V Raman and A P J Abdul Kalam to to receive the Bharat Ratna. Source: Article, Image: flickr.com