Friday, 26 December 2025

Stunning Crocheted Christmas Tree Helped Knit Together a Community of Extraordinary Women - LOOK

Gender-neutral clothing challenging societal norms

Tuesday, 2 September 2025

‘Mile Long Table’ in Denver Seats Thousands of Strangers to Eat and Celebrate Community Together

Mile Long Table in Denver – Credit: Longer Tables

Mile Long Table in Denver – Credit: Longer Tables Credit: Longer Tables

Credit: Longer TablesFriday, 1 August 2025

Famous Pastor John MacArthur Died at 86: Who is He Who Taught the Bible to the World?

Wednesday, 30 July 2025

Japan births in 2024 fell below 700,000 for first time

Thursday, 10 July 2025

Dozens of Free Summer Camps Opened By Paul Newman Give Sick Kids and Their Families ‘Serious Fun’

Friday, 4 July 2025

Golden Wheat Anniversary: Farmer Uses Crop Field to Create One-Mile Message for Wife of 20 Years

Friday, 23 May 2025

Vietnam: Holy relics of Lord Buddha sent from India arrive in Hanoi

Hanoi, (IANS) The sacred relics of Lord Buddha from India were enshrined in the Buddhist temple Quan Su Pagoda in Hanoi on Tuesday with ceremonial ritual and prayers conducted by monks from India and Vietnam. The relics will be displayed in the Buddhist temple till May 16.

Wednesday, 14 May 2025

How to learn a language like a baby

Learning a new language later in life can be a frustrating, almost paradoxical experience. On paper, our more mature and experienced adult brains should make learning easier, yet it is illiterate toddlers who acquire languages with apparent ease, not adults.

Babies start their language-learning journey in the womb. Once their ears and brains allow it, they tune into the rhythm and melody of speech audible through the belly. Within months of birth, they start parsing continuous speech into chunks and learning how words sound. By the time they crawl, they realise that many speech chunks label things around them. It takes over a year of listening and observing before children say their first words, with reading and writing coming much later.

However, for adults learning a foreign language, the process is typically reversed. They start by learning words, often from print, and try to pronounce them before grasping the language’s overall sound.

Tuning in to a new language

Our new study shows that adults can quickly pick up on the melodic and rhythmic patterns of a completely novel language. It confirms that the relevant native-language acquisition mechanism remains intact in the adult brain.

In our experiment, 174 Czech adults listened to 5 minutes of Māori, a language they had never heard. They were then tested on new audio clips from either Māori or Malay – another unfamiliar but similar language – and asked to say if they were hearing the same language as before or not.

The test phrases were acoustically filtered to mimic speech heard in the womb. This preserved melody and rhythm, but removed the frequencies higher than 900 Hz which contain consonant and vowel detail.

Listeners correctly distinguished the languages more often than not, showing that even very brief exposure was enough for them to implicitly grasp a language’s melodic and rhythmic patterns, much like babies do.

However, during the exposure phase, only one group of participants simply listened – three other groups listened while reading subtitles. The subtitles were either in the original Māori spelling where speech sounds consistently map onto specific letters (similar to Spanish), altered to reduce sound-letter correspondence (like in English, for example “sight”, “site”, “cite”), or they were transliterated to a script unknown to any of the participants (Hebrew).

The results showed that reading alphabetic spellings actually hampered the adults’ sensitisation to the overall melody and rhythm of the novel language, reducing their test performance. As complete beginners, the participants were able to learn more Māori without textual aids of any kind.

Initial illiteracy helps learning

Our research builds on previous studies, which have found that spelling can interfere with how learners pronounce individual vowels and consonants of a non-native language. Examples among learners of English include Italian learners lengthening double letters, or Spaniards confusing words like “sheep” and “ship” due to how “i” and “e” are read in Spanish.

Our study shows that spelling can even hinder our natural ability to listen to speech melody and rhythm. Experts looking for ways to reawaken adults’ language-learning capabilities should therefore consider the potentially negative impact of premature exposure to alphabetic spelling in a foreign language.

Early studies have proposed that a putative “sensitive period” for acquiring the sound patterns of a language ends around age 6. Not coincidentally, this is the age when many children learn to read. There is also research on infants that shows that starting with the global features of speech, such as its melody and rhythm, serves as a gateway to other levels of the native language.

A reversed approach to language learning – one that begins with written forms – may indeed undercut adults’ sensitisation to the melody and rhythm of a foreign language. It affects their ability to perceive and produce speech fluently and, by extension, other linguistic competences like grammar and vocabulary usage.

A study with first- and third-graders confirms that illiterate children learn a new language differently from literate children. Non-readers were much better at learning which article went with which noun (like in the Italian “il bambino” or “la bambina”) than at learning individual nouns. In contrast, readers’ learning was influenced by the written form, which puts a space between articles and nouns.

Learn like a baby

Listening without reading letters may help us to stop focusing on individual vowels, consonants and separate words, and instead absorb the overall flow of a language much like infants do. Our research suggests that adult learners might benefit from adopting a more auditory-focused approach – engaging with spoken language first before introducing reading and writing.

The implications for language teaching are significant. Traditional methods often place a heavy emphasis on reading and writing early on, but a shift toward immersive listening experiences could accelerate spoken proficiency.

Language learners and educators alike should therefore consider adjusting their methods. This means tuning in to conversations, podcasts, and native speech from the earliest stage of language learning, and not immediately seeking out the written word.![]()

Kateřina Chládková, Assistant professor, Charles University; Šárka Šimáčková, assistant professor, Palacky University Olomouc, and Václav Jonáš Podlipský, Assistant Professor of English Phonetics, Palacky University Olomouc

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Children in need of ‘rescuing’: challenging the myths at the heart of the global adoption industry

Korean adoptees worldwide are grappling with a devastating possibility: they were not truly orphans, but may have been made into orphans.

For decades, adoptees were told they were “abandoned”, “rescued” or “unwanted”. Many were told their Korean families were too “poor” or “incapable” to raise them – and they should only ever feel grateful for being adopted.

But these long-held stories are now under scrutiny.

Our recent research interrogates the narratives that have obscured the darker realities of intercountry adoption. Rather than viewing adoption solely through the lens of “rescue”, our work examines the broader power structures that facilitated the mass migration of Korean children to western countries, including Australia.

South Korea’s reckoning with its adoption history

In March, South Korea’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission released its preliminary findings after collecting records and testimony from a coalition of overseas Korean adoptee-led organisations (including the Australia–US Korean Rights Group).

The preliminary report revealed a disturbing pattern of human rights violations in the country’s adoption industry, including:

- forced relinquishments

- falsified records

- babies switched at adoption

- inadequate screening processes, and

- deep-rooted institutional corruption.

The commission’s chair described finding

serious violations of the rights of adoptees, their biological parents – particularly Korean single mothers – and others involved. These violations should never have occurred.

The commission is expected to release its final report soon, but due to the upcoming presidential election and political uncertainty in South Korea, the timeline remains unclear.

Chilling cases

This is not the first time intercountry adoption has made headlines for irregularities, human rights abuses, or illicit and illegal practices.

While Australia was expanding the number of children for intercountry adoption from South Korea in the 1980s, Park In-keun – director of South Korea’s infamous Brothers Home, an illegal detention facility that sent children overseas for adoption – was arrested for embezzlement and illegal confinement.

He was ultimately acquitted of the most serious charges in South Korea before escaping to Australia. He was then charged again in 2014 for embezzlement, including government subsidies and wages of inmates forced into slave labour in South Korea. He died two years later.

Other allegations of human rights violations and abuses came to light around the same time with the arrest of Julie Chu.

She was accused of facilitating a “baby export” syndicate. Children were believed to have been kidnapped from Taiwan to send to Western countries, including Australia, in the 1970s and 80s. She was convicted of forgery, but denied being involved in trafficking.

Since then, other cases have continued to emerge involving countries such as Chile, Sri Lanka, India, Ethiopia and Guatemala.

What is the adoption industrial complex?

Intercountry adoption is not just a social practice. It’s also an economic and political system sometimes known as the transnational adoption industrial complex.

This network of organisations, institutions, government policies and financial systems created a globalised adoption economy worth billions of dollars. According to numerous investigations, Western nations, as “receiving” countries, drove the demand for the continuous sourcing of children.

As Park Geon-Tae, a senior investigator with South Korea’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, said:

To put it simply, there was supply because there was demand.

Australia received an estimated 3,600 Korean children from the 1970s to the present, as part of more than 10,000 intercountry adoptions.

Prospective parents typically paid between US$4,500 and $5,000 to facilitate acquiring a child in Australia in the 1980s, equivalent to A$21,000 today.

Since colonisation, Australia has had a long and painful history of child removal. From the Stolen Generations involving First Nations children to the forced adoption of children born to unwed mothers, child separation has been deeply embedded in the nation’s social policy.

While national apologies have acknowledged the irreparable harms caused by these policies, the same ideologies and structures were repurposed as the blueprint for intercountry adoption.

In recent years, other western nations, such as Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Sweden and Switzerland, have begun to investigate their own roles in the intercountry adoption industry. These nations have either suspended their adoption programs, issued formal apologies or launched formal investigations.

Thus far, Australia and the United States have not.

Challenging the ‘rescue’ myth

Intercountry adoption has long been framed as a humanitarian act. The central idea was that children needed “rescuing” and any life in a Western country would be “better” than one with their families in their home country.

Many adoptees and their original families were expected to just move on or be grateful for being “saved”.

However, research shows this gratitude narrative disregards the deep trauma caused by forced separation.

Studies have reported that adoptees experience lifelong ruptures due to cultural, familial and ancestral displacement. Forced assimilation makes reconnection with family and culture complex or nearly impossible.

Many intercountry adoptees have also voiced concerns about abuse, violence and mistreatment in adoptive homes.

Questioning the ‘orphan crisis’ myth

The myth of a global orphan crisis has also been a powerful driver of intercountry adoption.

Adoption groups often reference outdated UNICEF estimates that there are 150 million orphans globally. However, this figure obscures the fact most of the children classified as “orphans” are children of single parents, or children currently living in homes with extended family or other caregivers.

This was the case in South Korea. Most children sent for adoption were not true orphans, but children who had at least one parent or extended family they could have stayed with if they were adequately supported.

The belief that millions of children of single parents were “orphans” in need of “rescue” was used to justify calls for faster, less regulated adoptions.

Labelling these children as “orphans” also helped attract millions of dollars in philanthropic donations. However, donors were rarely interested in supporting children to stay with their families and communities in their home countries.

Instead, the focus was often on removing and migrating them for the purpose of intercountry adoption.

The question then emerges: was this about finding families for babies or finding babies for Western families?![]()

Samara Kim, PhD Candidate & Researcher, Southern Cross University; Kathomi Gatwiri, Associate Professor, Southern Cross University, and Lynne McPherson, Associate Professor, Southern Cross University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Monday, 12 May 2025

World leaders welcome first US pope

Saturday, 12 April 2025

Neighbors Celebrate 101st Birthday On the Same Day–Living Next Door to Each Other For 4 Decades

Tuesday, 11 March 2025

10-Year-old Paramedic Teaches Adults Lifesaving Skills and CPR as ‘The Mini Medic’

Monday, 10 March 2025

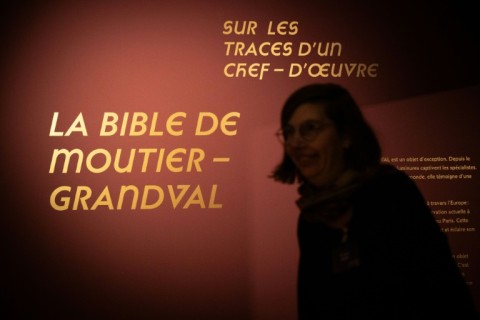

Priceless ninth-century masterpiece Bible returns to Swiss homeland

Friday, 28 February 2025

Most Single Americans Look for Partners With These Career Values and Passions: New Dating Poll - Good News Network

- Passion for what they’re doing — 40%

- Prioritizing work/personal life balance — 34%

- Understanding that there is always more to learn/ways to improve — 28%

- Ability to work well with others and build relationships with colleagues — 25%

- Desire to leave a positive impact on society or other people — 21%

- Competitiveness or wanting to be successful — 19%

- Desire to leave a positive impact on the environment — 15%

- Desire to be a good manager or leader — 15%

- Commitment to pushing the boundaries and paving new roads — 15%, Most Single Americans Look for Partners With These Career Values and Passions: New Dating Poll - Good News Network

Friday, 14 February 2025

Dealing with love, romance and rejection on Valentine’s Day

Lisa A Williams, UNSW Sydney

Take care lovers, wherever you are, as Valentine’s Day is soon upon us. Whether you’re in a relationship or want to be in a relationship, research over a number of years shows that February 14 can be a day of broken hearts and broken wallets.

A study by US psychologists in 2004 found that relationship breakups were 27% to 40% higher around Valentine’s Day than at other times of the year. Fortunately, this bleak trend was only found amongst couples on a downward trajectory who weren’t the happiest to begin with.

For stable or improving couples, Valentine’s Day thankfully didn’t serve as a catalyst for breakup. (That said, science has more to say on the predictions of any breakup in a relationship.)

But it’s hard to avoid the pressure of Valentine’s Day. This time of year, television, radio, printed publications and the internet are littered with advertisements reminding people of the upcoming celebration: Buy a gift! Make a reservation! Don’t forget the flowers! And by all means be romantic!.

Think you’re safe and single? Not so fast – ads urging those not in romantic relationships to seek one out (namely, via fee-based dating websites) are rife this time of year.

The origins of Valentine’s Day go back many centuries and it is a time of dubious repute. Originally it was a day set aside to celebrate Christian saints named Valentine (there were many). The association with romantic love was only picked up in the UK during the Middle Ages. Thank you, Chaucer and Shakespeare.

Mass-produced paper Valentines appeared on the scene in the 1800s, and it seems that the commercialisation of the day has increased ever since. Now, many refer to Valentine’s Day as a “Hallmark Holiday” – a reference to the popular producer of many Valentine’s cards.

No matter the history, or whether you are a conscientious objector to the commercialisation of love, it is difficult not to get swept up in the sentiment.

Despite the research (mentioned earlier) that Valentine’s Day can be calamitous for some, other research speaks to how to make this day a positive and beneficial one for you and your loved ones.

My funny Valentine

For those not in a romantic relationship, it’s hard to avoid the normative message that you are meant to be in one. But is it worth risking social rejection by asking someone for a date on Valentine’s Day?Unfortunately, science can’t answer that one. What we do know is that social rejection hurts –- literally – according to Professor Naomi Eisenberger, a social psychologist and director of the Social and Affective Neuroscience Laboratory at UCLA. She found that being socially rejected results in activation in the same brain areas that are active during physical pain.

Even though we may treat physical pain more seriously and regard it as the more valid ailment, the pain of social loss can be equally as distressing, as demonstrated by the activation of pain-related neural circuitry upon social disconnection.

A low dose of over-the-counter pain-killer can buffer against the sting of rejection. And, as silly as it seems, holding a teddy bear after the fact can provide relief.

If you do decide to seek a partner, dating websites and smartphone apps are a popular option. In 2013, 38% of American adults who were “single and looking” used dating websites or apps.

Dating websites such as eHarmony even claim to use scientific principles in their matching system (though this claim has been heavily critiqued by relationship researchers).

On this point, US psychology professor Eli Finkel provides a timely commentary on smartphone dating apps such as Tinder. He says he can see the benefits but he also points out that “algorithm matchmaking” is still no substitute for the real encounter.

As almost a century of research on romantic relationships has taught us, predicting whether two people are romantically compatible requires the sort of information that comes to light only after they have actually met.

The multi-billion dollar dating website industry would have you think it is a path to true-love. Though the fact of the matter is, despite several studies, we simply don’t know if dating websites are any more effective than more traditional approaches to mate-finding. So, on this point, single-and-looking payer beware.

Can’t buy me love

Speaking of money, the consumerism surrounding Valentine’s Day is undeniable. Australians last year spent upwards of A$791 million on gifts and such. Americans are estimated to spend US$19 billion (A$24 billion) this year.

Spending in and of itself, however, isn’t a bad thing. It turns out it’s how you spend that matters.

First, given the choice between buying a thing and buying an experience – ongoing research by Cornell University’s psychology professor Thomas Gilovich favours opting for the latter. Chances are, you’ll be happier.

In the case of Valentine’s Day, spending on a shared experience will make your partner happier too – research from US relationship researcher Art Aron suggests that spending on a shared experience will reap more benefit than a piece of jewelry or a gadget, especially to the extent that this shared experience is new and exciting.

Second, if you’re going to part with that cash in the end, you might as well spend it on someone else. Across numerous experiments (see here, here, here, here and here), individuals instructed to spend on others experienced greater happiness than those instructed to spend the same amount on themselves.

The effect is even stronger if you spend that money on a strong social bond, such as your Valentine.

Third, if you do give a gift, you’re best to pay heed to any dropped hints by your partner about desired gifts.

This is especially the case if your loved one is a man. In one study, men who received an undesired gift from their partners became pessimistic about the future of their relationship. Women didn’t react quite so poorly to a bad gift.

All you need is love

Of course, don’t think that love is just for lovers – even on Valentine’s Day.

Love Actually anyone?

Given the robustly supported conclusion that close non-romantic friendships can be just as rewarding (and health promoting) as romantic relationships, an alternative is to treat Valentine’s Day as an opportunity to celebrate all of your social relationships.

Scientific research supports the benefits of the following, simple (and free) acts:

a thank you note can boost relationships of all types

a hug can make both parties happier and even less stressed

simply engaging in chit-chat with those around you could be extremely rewarding

just a few minutes of loving-kindness mediation – wishing for happiness for yourself and those around you – can lead to a sense of deeper connection with others.

If all else fails on Valentine’s Day, then settle back and listen to Stephen Stills’ classic song Love The One You’re With: “If you can’t be with the one you love, love the one you’re with.”![]()

Lisa A Williams, Lecturer, School of Psychology, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.