Monday, 5 January 2026

'It Feels Like Me Again': World’s First Arm Exoskeleton Gives Stroke Patients Independence

Thursday, 11 December 2025

Innovative Tapeless Zipper Saves Tons of Fabric While Creating a Better Fit on Your Clothes

At Japan’s YKK, they’ve debuted a zipper sans fabric tape—the typically black-colored strip of material that separates the back of the zipper teeth from the garment.

Descente Japan was among the first to prototype AiryString® in 2022. The North Face has selected the system for use in its new Summit Series Advanced Mountain Kit, and the reception is positive—with users testifying to flexibility, lighter weight, a more unifying design, and a better, more natural fit. The secret behind is that zipper teeth are actually more bendy and twisty than the fabric tape they attach to, and that if you attach them directly to the garment, these properties are conferred to it.

But how can a zipper attach directly to fabric?

Don’t worry, all your questions can be answered in the pair of videos below. But for now, have a read about the impressive potential this upgraded zipper can bring the world.

The beforementioned YKK has an unusual level of market dominance. It owns not only patents and/or trademarks on its finished products in 180 countries, but also on a suite of sewing machines that the company manufactures itself. In addition to this, it designs and makes its own molds for zippers, and even spins its own thread.

With so much supply chain security, YKK can afford to innovate in a way that others can’t. In fact, one could be applauded for pointing out that YKK is as much if not more of a monopoly than Standard Oil ever was.

Since the modern zipper’s debut in 1910, there’s been little need for innovation. Textile and garment fabrication, however, rarely rests, and today brands wield “smart fabrics” featherweight nylon blends, and other extremely innovative fabrics that have left the zipper, in the words of Wired Magazine writer Amy Francombe, “out of sync with what surrounds it.”

It’s ironic to think of a zipper being out of sync, but indeed the stiff stitching along the tape-teeth seam makes for a less-flexible bind than do the newly redesigned teeth on the AiryString.

Without that tape though, YKK had to redesign everything. New machinery had to be developed to sew and close the garment. The resulting tapeless zipper seems impossible, but it’s anything but.

The sewing room floor has benefited by the change, as has the planet. Thousands of yards of fabric tape scraps are generated during zipper production, as well as gallons of water used with dye to color the tape—all of which have been removed. Add in shorter labor hours, and the result is a more efficient, eco-friendly product.

It’s attached to the garment via a sewing machine that feeds each half of the zipper along two gears made of the same zipper teeth as the AiryString.

YKK representatives told Francombe that adoption will take time, as the machines are not readily available, even if the zipper can fit into regular workflows. This has limited it to high-end brands, but if it proves popular, there’s virtually no limit to its future.

Personally, GNN would like to hear from users about whether the new teeth are easier to unjam in situations where the garment’s fabric gets stuck between them.WATCH how it works below… Innovative Tapeless Zipper Saves Tons of Fabric While Creating a Better Fit on Your Clothes

Tuesday, 9 December 2025

Passing on a family business isn’t easy. Here’s why – and what factors predict success

Francesco Chirico, Macquarie University

Earlier this year, the world watched with interest as the Murdoch family’s real-life Succession drama came to a close.

Media mogul Rupert Murdoch’s children – eyeing an empire estimated to be worth more than US$20 billion (A$30 billion) and control of the Fox Corporation and News Corporation – had disputed a change to their trust that would put control squarely in the hands of only one of his heirs, Lachlan.

A settlement was reached in September, giving Lachlan control and paying three of his siblings to exit.

But the very public and bitter battle was a classic example of the factors at play in succession planning for any family business. In addition to the business implications, it’s often fraught with emotion and power struggles.

For a country such as Australia, which is heavily reliant on family firms, these tensions matter far beyond the headlines. Understanding why succession is difficult – and how to get it right – is essential.

Powerhouse of the economy

Family-owned businesses are a crucial part of Australia’s economy. Small and medium-sized firms account for about 99% of all businesses, with about 70% being family-owned.

Surviving over time can be challenging. The “30-13-3” statistic (30% of firms transition to the second generation, 13% to the third, and 3% beyond that) is well known, despite some researchers now calling it into question.

Global evidence indicates only a minority of family firms successfully transition across multiple generations.

Emotional ties

A major part of what sets family businesses apart from other types of firms relates to what I and other family business scholars call “socioemotional wealth”.

This describes the emotional value families place on their business: legacy, identity, reputation, continuity and the comfort of keeping decision-making “in the family”.

These emotional bonds can be a source of strength. Research has shown family firms can be remarkably steady during moments of upheaval, including mergers and acquisitions and periods of financial distress because they prioritise long-term stability and trust.

But they also explain why successions can become so fraught. When leadership transitions threaten a family’s legacy, identity or long-standing traditions, emotions intensify.

Parents and earlier generations can feel they’re not just losing a role, they’re also losing a part of themselves. They may also make strategic decisions driven only by emotions, leading to conflicts, financial disruption and potential failure.

Kendall, second-eldest son of the fictional Roy family tries negotiating with father Logan in the HBO series Succession.

Openness to change

A recent study of mine adds another important layer, suggesting families adopt one of two mindsets.

One sees reality as relatively fixed, with families cautious of risks that might destabilise their legacy. The other views the business as flexible and adaptable.

These contrasting mindsets may help explain why some successions unfold smoothly – and others erupt into conflict. Families with the latter mindset tend to be more willing to let the next generation reshape the business.

The next generation

Australia is heading for a A$3.5 trillion generational wealth transfer, one of the biggest shifts of assets in its history. This will include many family businesses.

At the same time, digital transformation is reshaping every industry – from agriculture to construction to retail.

Younger successors tend to be digital natives. They often arrive fluent in data analytics, automation and artificial intelligence (AI). Many grew up in environments where constant change was the norm, meaning they naturally lean towards adaptability and flexibility.

Older leaders, particularly founders, often lean the other way. Deeply connected to the business they built, they are shaped by decades of experience and success.

The same socioemotional wealth that sustained the firm can make them reluctant to hand over control or adopt untested digital tools.

Soon-to-be-published research of mine with Nidthida Lin at Macquarie University Innovation, Strategy and Entrepreneurship (ISE) Research Centre has explored the way in Australian family firms, founder influence and long periods of stability often reinforce a mindset that favours tradition and caution. In contrast, family control and a strong desire for dynastic succession, together with the involvement of later generations, tend to encourage change and the adoption of AI technologies.

That tension, between preserving the legacy and the desire to reinvent it, is now one of the biggest challenges Australian family firms face in ensuring “the show goes on”.

Getting it right

Succession planning is not just a financial or legal process. Families need to acknowledge the emotions and feelings involved, including love, fear, grief, pride and ambition.

Avoiding these conversations only increases the risk of misunderstanding and resentment.

Other important steps for success include:

- creating a governance structure – a clear set of rules and roles that guide how the family and the business make decisions

- empowering the next generation to lead the digital transformation, and

- testing the succession plan before a crisis.

Preparing early

The good news is businesses can prepare for this change well in advance. A good example of succession planning comes from family-owned Australian office supplies company, COS. COS has an annual revenue of A$300 million and more than 600 employees, as well as warehouses in every state.

When founder Dominique Lyone died suddenly in 2024, his two daughters, Amie and Belinda, had already stepped into positions as co-chief executive officers, thanks to a smooth succession plan he had initiated many years earlier.

Getting succession right is not just about choosing the next leader. It is about understanding the emotional foundations of the family, recognising the mindsets driving decisions and creating a path that makes room for the future.![]()

Francesco Chirico, Professor of Strategy and Family Business, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Monday, 8 December 2025

Tongue-Zapping Device Does More in 6 Months Than 4 Years of Normal Stroke Rehabilitation

Friday, 5 December 2025

Cassette tapes are making a comeback. Yes, really

For a supposedly obsolete music format, audio cassette sales seem to be set on fast forward at the moment.

Cassettes are fragile, inconvenient and relatively low-quality in the sound they produce – yet we’re increasingly seeing them issued by major artists.

Is it simply a case of nostalgia?

Press play

The cassette format had its heyday during the mid-1980s, when tens of millions were sold each year.

However, the arrival of the compact disc (CDs) in the 1990s, and digital formats and streaming in the 2000s, consigned cassettes to museums, second-hand shops and landfill. The format was well and truly dead until the past decade, when it started to reenter the mainstream.

According to the British Phonographic Industry, in 2022 cassette sales in the United Kingdom reached their highest level since 2003. We’re seeing a similar trend in the United States, where cassette sales were up 204.7% in the first quarter of this year (a total of 63,288 units).

A number of major artists, including Taylor Swift, Billie Eilish, Lady Gaga, Charli XCX, the Weeknd and Royel Otis have all released material on cassette. Taylor Swift’s latest album, The Life of a Showgirl, is available in 18 versions across CDs, vinyl and cassettes.

The physical product offerings for Taylor Swift’s latest album, The Life of a Showgirl. Taylor Swift

The physical product offerings for Taylor Swift’s latest album, The Life of a Showgirl. Taylor SwiftMany news article will tell you a “cassette revival” is well underway. But is it?

I would argue what we’re seeing now is not a full-blown revival. After all, the unit sales still pale in comparison to the peak in the late 1990s, when some 83 million were reportedly sold in one year in the UK alone.

Instead, I see this as a form of rediscovery – or for young listeners, discovery.

Time to pause

Recorded music today is mostly heard through digital channels such as Spotify and social media.

Meanwhile, cassettes break and jam quite easily. Choosing a particular song might involve several minutes of fast forwarding, or rewinding, which clogs the playback head and weakens the tape over time. The audio quality is low, and comes with a background hiss.

Why resurrect this clunky old technology when everything you could want is a languid tap away on your phone?

Analogue formats such as cassettes and vinyl are not prized for their sound, but for the tactility and sense of connection they provide. For some listeners, cassettes and LPs allow for a tangible connection with their favourite artist.

There’s an old joke about vinyl records that people get into them for the expense and the inconvenience. The same could be said for cassette tapes: our renewed interest in them could be read as a questioning (if not rejection) of the blandly smooth, ubiquitous and inescapable digital world.

The joy of the cassette is its “thingness”, its “hereness” – as opposed to an intangible string of electrical impulses on a far-flung corporate-owned server.

The inconvenience and effort of using cassettes may even make for more focused listening – something the invisible, ethereal and “instantly there” flow of streaming doesn’t demand of us.

People may also choose to buy cassettes for the nostalgia, for their “retro” cool aesthetic, to be able to own music (instead of streaming it), and to make cheap and quick recordings.

Mix tape mania

Cassettes did (and still do) have the whiff of the rebel about them. As researcher Mike Glennon explains, they give consumers the power to customise and “reconfigure recorded sound, thus inserting themselves into the production process”.

From the 1970s, blank cassettes were a cheap way for anyone to record anything. They offered limitless combinations and juxtapositions of music and sounds.

The mix tape became an art form, with carefully selected track sequences and handmade covers. Albums could even be chopped up and rearranged according to preference.

Consumers could also happily copy commercial vinyl and cassettes, as well as music from radio, TV and live gigs. In fact, the first single ever released on cassette, Bow Wow Wow’s C30,C60,C90,Go! (1980), extolled the joys and righteousness of home taping as a way of sticking it to the man – or in this case the music industry.

Unsuprisingly, the recording industry saw cassettes and home taping as a threat to its copyright-based income and struck back.

In 1981, the British Phonographic Industry launched its infamous “home taping is killing music” campaign. But the campaign’s somewhat pompous tone led to it being mercilessly mocked and largely ignored by the public.

A chance to rewind

The idea of the blank cassette as both a symbol of self-expression and freedom from corporate control continues to persist. And today, it’s not only corporate control consumers have to dodge, but also the dominance of digital streaming platforms.

Far from being just a pleasant yearning sensation, nostalgia for older technology is layered, complex and often political.

Cassettes are cheap and easy to make, so many artists past and present have used them as merchandise to sell or give away at gigs and fan events. For hardcore fans, they are solid tokens of their dedication – and many fans will buy multiple formats as a form of collecting.

Cassettes won’t replace streaming services anytime soon, but that’s not the point. What they offer is a way of listening that goes against the grain of the digital hegemony we find ourselves in. That is, until the tape snaps.![]()

Peter Hoar, Senior Lecturer, School of Communications Studies, Auckland University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Friday, 28 November 2025

Would Your Helmet Actually Protect You? VA Tech’s ‘Helmet Lab’ Is Testing Every Sport

Thursday, 20 November 2025

Giant 7’9” Canadian is Tallest Player in College Basketball History, Dunking Without Jumping (WATCH)

Wednesday, 12 November 2025

The Roman empire built 300,000 kilometres of roads: new study

At its height, the Roman empire covered some 5 million square kilometres and was home to around 60 million people. This vast territory and huge population were held together via a network of long-distance roads connecting places hundreds and even thousands of kilometres apart.

Compared with a modern road, a Roman road was in many ways over-engineered. Layers of material often extended a metre or two into the ground beneath the surface, and in Italy roads were paved with volcanic rock or limestone.

Roads were also furnished with milestones bearing distance measurements. These would help calculate how long a journey might take or the time for a letter to reach a person elsewhere.

Thanks to these long-lasting archaeological remnants, as well as written records, we can build a picture of what the road network looked like thousands of years ago.

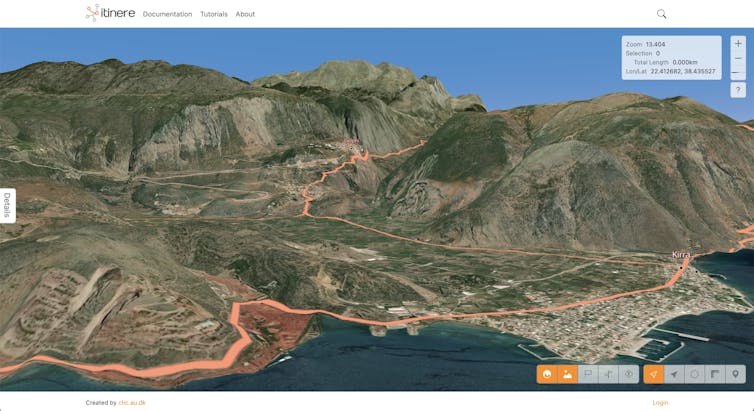

A new, comprehensive map and digital dataset published by a team of researchers led by Tom Brughmans at Aarhus University in Denmark shows almost 300,000 kilometres of roads spanning an area of close to 4 million square kilometres.

The road network

The Itiner-e dataset was pieced together from archaeological and historical records, topographic maps, and satellite imagery.

It represents a substantial 59% increase over the previous mapping of 188,555 kilometres of Roman roads. This is a very significant expansion of our mapped knowledge of ancient infrastructure.

The Via Appia is one of the oldest and most important Roman roads. LivioAndronico2013 / Wikimedia, CC BY

The Via Appia is one of the oldest and most important Roman roads. LivioAndronico2013 / Wikimedia, CC BYAbout one-third of the 14,769 defined road sections in the dataset are classified as long-distance main roads (such as the famous Via Appia that links Rome to southern Italy). The other two-thirds are secondary roads, mostly with no known name.

The researchers have been transparent about the reliability of their data. Only 2.7% of the mapped roads have precisely known locations, while 89.8% are less precisely known and 7.4% represent hypothesised routes based on available evidence.

More realistic roads – but detail still lacking

Itiner-e has improved on past efforts with improved coverage of roads in the Iberian Peninsula, Greece and North Africa, as well as a crucial methodological refinement in how routes are mapped.

Rather than imposing idealised straight lines, the researchers adapted previously proposed routes to fit geographical realities. This means mountain roads can follow winding, practical paths, for example.

Itiner-e includes more realistic terrain-hugging road shapes than some earlier maps. Itiner-e, CC BY

Itiner-e includes more realistic terrain-hugging road shapes than some earlier maps. Itiner-e, CC BYAlthough there is a considerable increase in the data for Roman roads in this mapping, it does not include all the available data for the existence of Roman roads. Looking at the hinterland of Rome, for example, I found great attention to the major roads and secondary roads but no attempt to map the smaller local networks of roads that have come to light in field surveys over the past century.

Itiner-e has great strength as a map of the big picture, but it also points to a need to create localised maps with greater detail. These could use our knowledge of the transport infrastructure of specific cities.

There is much published archaeological evidence that is yet to be incorporated into a digital platform and map to make it available to a wider academic constituency.

Travel time in the Roman empire

Fragment of a Roman milestone erected along the road Via Nova in Jordan. Adam Pažout / Itiner-e, CC BY

Fragment of a Roman milestone erected along the road Via Nova in Jordan. Adam Pažout / Itiner-e, CC BYItiner-e’s map also incorporates key elements from Stanford University’s Orbis interface, which calculates the time it would have taken to travel from point A to B in the ancient world.

The basis for travel by road is assumed to have been humans walking (4km per hour), ox carts (2km per hour), pack animals (4.5km per hour) and horse courier (6km per hour).

This is fine, but it leaves out mule-drawn carriages, which were the major form of passenger travel. Mules have greater strength and endurance than horses, and became the preferred motive power in the Roman empire.

What next?

Itiner-e provides a new means to investigate Roman transportation. We can relate the map to the presence of known cities, and begin to understand the nature of the transport network in supporting the lives of the people who lived in them.

This opens new avenues of inquiry as well. With the network of roads defined, we might be able to estimate the number of animals such as mules, donkeys, oxen and horses required to support a system of communication.

For example, how many journeys were required to communicate the death of an emperor (often not in Rome but in one of the provinces) to all parts of the empire?

Some inscriptions refer to specifically dated renewal of sections of the network of roads, due to the collapse of bridges and so on. It may be possible to investigate the effect of such a collapse of a section of the road network using Itiner-e.

These and many other questions remain to be answered.![]()

Ray Laurence, Professor of Ancient History, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tuesday, 11 November 2025

New discovery reveals chimpanzees in Uganda use flying insects to tend their wounds

Kayla Kolff, Osnabrück University

Animals respond to injury in many ways. So far, evidence for animals tending wounds with biologically active materials is rare. Yet, a recent study of an orangutan treating a wound with a medicinal plant provides a promising lead.

Chimpanzees, for example, are known to lick their wounds and sometimes press leaves onto them, but these behaviours are still only partly understood. We still do not know how often these actions occur, whether they are deliberate, or how inventive chimpanzees can be when responding to wounds.

Recent field observations in Uganda, east Africa, are now revealing intriguing insights into how these animals cope with wounds.

As a primatologist, I am fascinated by the cognitive and social lives of chimpanzees, and by what sickness-related behaviours can reveal about the evolutionary origins of care and empathy in people. Chimpanzees are among our closest living relatives, and we can learn so much about ourselves through understanding them.

In our research based in Kibale National Park, Uganda, chimpanzees have been seen applying insects to their own open wounds on five occasions, and in one case to another individual.

Behaviours like insect application show that chimpanzees are not passive when wounded. They experiment with their environment, sometimes alone and occasionally with others. While we should not jump too quickly to call this “medicine”, it does show that they are capable of responding to wounds in inventive and sometimes cooperative ways.

Each new insight adds reveals more about chimpanzees, offering glimpses into the shared evolutionary roots of our own responses to injury and caregiving instincts.

First catch your insect

We saw the insect applications by chance while observing and recording their behaviour in the forest, but paid special attention to chimpanzees with open wounds.Insect application by subadult Damien.

In all observed cases, the sequence of actions seemed deliberate. A chimpanzee caught an unidentified flying insect, immobilised it between lips or fingers, and pressed it directly onto an open wound. The same insect was sometimes reapplied several times, occasionally after being held briefly in the mouth, before being discarded. Other chimpanzees occasionally watched the process closely, seemingly with curiosity.

Most often the behaviour was directed at the chimpanzee’s own open wound. However, in one rare instance, an adolescent female applied an insect to her brother’s wound. A study on the same community has shown that chimpanzees also dab the wounds of unrelated members with leaves, prompting the question of whether insect application of these chimpanzees, too, might extend beyond family members. Acts of care, whether directed towards family or others, can reveal the early foundations of empathy and cooperation.

The observed sequence closely resembles the insect applications seen in Central chimpanzees in Gabon, Africa. The similarity suggests that insect application may represent a more widespread behaviour performed by chimpanzee than previously recognised.

The finding from Kibale National Park broadens our view of how chimpanzees respond to wounds. Rather than leaving wounds unattended, they sometimes act in ways that appear deliberate and targeted.

Chimpanzee first aid?

The obvious question is what function this behaviour might serve. We know that chimpanzees deliberately use plants in ways that can improve their health: swallowing rough leaves that help expel intestinal parasites or chewing bitter shoots with possible anti-parasitic effects.

Insects, however, are a different matter. Pressing insects onto wounds has not yet been shown to speed up healing or reduce infection. Many insects do produce antimicrobial or anti-inflammatory substances, so the possibility is there, but scientific testing is still needed.

For now, what we can say is that the behaviour appears to be targeted, patterned and deliberate. The single case of an insect being applied to another individual is especially intriguing. Chimpanzees are highly social animals, but active helping is relatively rare. Alongside well-known behaviours such as grooming, food sharing, and support in fights, applying an insect to a sibling’s wound hints at another form of care, one that goes beyond maintaining relationships to possibly improving the other’s physical condition.

Big questions

This behaviour leaves us with some big questions. If insect application proves medicative, it could explain why chimpanzees do it. This in turn raises the question of how the behaviour arises in the first place: do chimpanzees learn it by observing others, or does it emerge more spontaneously? From there arises the question of selectivity – are they choosing particular flying insects, and if so, do others in the group learn to select the same ones?

In human traditional medicine (entomotherapy), flying insects such as honeybees and blowflies are valued for their antimicrobial or anti-inflammatory effects. Whether the insects applied by chimpanzees provide similar benefits is still to be investigated.

Finally, if chimpanzees are indeed applying insects with medicinal value and sometimes placing them on the wounds of others, this could represent active helping and even prosocial behaviour. (The term is used to describe behaviours that benefit others rather than the individual performing them.)

Watching chimpanzees in Kibale National Park immobilise a flying insect and gently press it onto an open wound reminds us how much there is still to learn about their abilities. It also adds to the growing evidence that the roots of care and healing behaviours extend much further back in evolutionary time.

If insect applications prove to be medicinal, this adds to the importance of safeguarding chimpanzees and their habitats. In turn, these habitats protect the insects that can contribute to chimpanzee well-being.![]()

Kayla Kolff, Postdoctoral researcher, Osnabrück University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Thursday, 30 October 2025

The rise and fall of globalisation: why the world’s next financial meltdown could be much worse with the US on the sidelines

Steve Schifferes, City St George's, University of London

This is the second in a two-part series. Read part one here.

Globalisation has always had its critics – but until recently, they have come mainly from the left rather than the right.

In the wake of the second world war, as the world economy grew rapidly under US dominance, many on the left argued that the gains of globalisation were unequally distributed, increasing inequality in rich countries while forcing poorer countries to implement free-market policies such as opening up their financial markets, privatising their state industries and rejecting expansionary fiscal policies in favour of debt repayment – all of which mainly benefited US corporations and banks.

This was not a new concern. Back in 1841, German economist Friedrich List had argued that free trade was designed to keep Britain’s global dominance from being challenged, suggesting:

When anyone has obtained the summit of greatness, he kicks away the ladder by which he climbs up, in order to deprive others of the means of climbing up after him.

By the 1990s, critics of the US vision of a global world order such as the Nobel-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz argued that globalisation in its current form benefited the US at the expense of developing countries and workers – while author and activist Naomi Klein focused on the negative environmental and cultural consequences of the global expansion of multinational companies.

Mass left-led demonstrations broke out, disrupting global economic meetings including, most famously, the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1999. During this “battle of Seattle”, violent exchanges between protesters and police prevented the launch of a new world trade round that had been backed by then US president, Bill Clinton. For a while, the mass mobilisation of a coalition of trade unionists, environmentalists and anti-capitalist protesters seemed set to challenge the path towards further globalisation – with anti-capitalism “Occupy” protests spreading around the world in the wake of the 2008 financial crash.

A documentary about the 1999 ‘batte of Seattle’, directed by Jill Friedberg and Rick Rowley.

In the US, a further critique of globalisation centred on its domestic consequences for American workers – namely, job losses and lower pay – and led to calls for greater protectionism. Although initially led by trade unions and some Democratic politicians, this critique gradually gained purchase in radical right circles who opposed giving any role to international organisations like the WTO, on the grounds that they impinged on American sovereignty. According to this view, only by stopping foreign competition whose low wages undercut American workers could prosperity be restored. Immigration was another target.

Under Donald Trump’s second term as US president, these criticisms have been transformed into radical, deeply disruptive economic and social policies – with tariffs and protectionism at their heart. In so doing, Trump – despite all his grandstanding on the world stage – has confirmed what has long been clear to close observers of US politics and business: that the American century of global dominance, with the dollar as unrivalled no.1 currency, is drawing rapidly to a close.

Even before Trump first took office in 2017, the US had begun to withdraw from its leadership role in international economic institutions such as the WTO. Now, the strongest part of its economy, the hi-tech sector, is under intense pressure from China, whose economy is already bigger than the US’s by one key measure of GDP. Meanwhile, the majority of US citizens are facing stagnant incomes, higher prices and more insecure jobs.

In previous centuries, when first France and then Great Britain reached the end of their eras of world domination, these transitions had painful impacts beyond their borders. This time, with the global economy more closely integrated than ever before and no single dominant power waiting in the wings to take over, the impacts could be felt even more widely – with very damaging, if not catastrophic, results.

Why no one is ready to take the US’s place

When it comes to taking over from the US as the world’s leading hegemonic power, the only viable candidates with big enough economies are the European Union and China. But there are strong reasons to doubt that either could take on this role – notwithstanding the fact that in 2022, then US president Joe Biden’s National Security Strategy called China: “The only competitor with both the intent to reshape the international order and, increasingly, the economic, diplomatic, military and technological power to do so.”

At times Biden’s successor, President Trump, has sounded almost jealous of the control China’s leaders exert over their national economy, and the fact they do not face elections and limits on their terms in office. But a one-party, authoritarian political system which lacks legal checks and balances is a key reason China will find it hard to gain the cultural and political dominance among democratic nations that is part of achieving world no.1 status – despite the influence it already wields in large parts of Asia and Africa.

China still faces big economic challenges too. While it is already the global leader in manufactured goods (rapidly moving into hi-tech products) and the world’s largest exporter, its economy is still very unbalanced – with a much smaller consumer sector, a weak property market, many inefficient state industries that are highly indebted, and a relatively small financial sector restricted by state ownership. Nor does China possess a global currency, despite its (limited) attempts to make the renminbi a truly international currency.

The Insights section is committed to high-quality longform journalism. Our editors work with academics from many different backgrounds who are tackling a wide range of societal and scientific challenges.

As I found on a reporting trip to Shanghai in 2007 to investigate the effects of globalisation, there are also enormous differences between China’s prosperous coastal megacities – whose main thoroughfares rival New York and Paris – and the relative poverty in the interior, especially in rural areas. But nearly two decades on from that visit, with the country’s growth rate slowing, many university-educated young people are also finding it hard to find well-paid jobs now.

Meanwhile Europe – the only other contender to take the US’s place as global no.1 – is deeply politically divided, with smaller, weaker economies to the east and south far more sceptical about the benefits of globalisation, and increasingly divided on issues such as migration and the Ukraine war. The challenges of achieving broad policy agreement among all member states, and the problem of who can speak for Europe, make it unlikely that the EU as currently constituted could initiate and enforce a new global world order on its own.

The EU’s financial system also lacks the heft of the US’s. Although it has a common currency (the euro) managed by the European Central Bank, its financial system is far more fragmented. Banks are regulated nationally, and each country issues its own government bonds (although a few eurobonds now exist). This makes it hard for the euro to replace the dollar as a store of value, and reduces the incentive for foreigners to hold euros as an alternative reserve currency.

Meanwhile, any future prospects of a renewal of US global leadership look similarly unpromising. Trump’s policy of cutting taxes while increasing the size of the US government debt – which now stands at US$38 trillion, or 120% of GDP – threatens both the stability of the world economy and the ability of the US to finance this mind-boggling deficit.US national debt hits record high. Video: The Economic Times.

Our current, nameless global order, which is dominated by the WTO and is notionally designed to pursue economic efficiency and regulate the trade policies of its 166 member countries, is untenable and unsustainable. The US has paid for this system with the loss of industrial jobs and economic security, and the biggest winner has been China.

While the US is not, so far, withdrawing from the IMF, the Trump administration has urged it to call out China for running such a large trade surplus, while abandoning its concern about climate change. Greer concluded that the US has “subordinated our country’s economic and national security imperatives to a lowest common denominator of global consensus”.

World without a global no.1

To understand the potential dangers ahead, we must go back more than a century to the last time there was no global hegemon. By the time the first world war officially ended with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on June 28 1919, the international economic order had collapsed. Britain, world leader over the previous century, no longer possessed the economic, political or military clout to enforce its version of globalisation.

The UK government, burdened by the huge debts it had taken out to finance the war effort, was forced to make major cuts in public spending. In 1931, it faced a sterling crisis: the pound had to be devalued as the UK exited from the gold standard for good, despite having yielded to the demands of international bankers to cut payments to the unemployed. This was a final sign that Britain had lost its dominant place in the world economic order.

The 1930s were a time of deep political unease and unrest in Britain and many other countries. In 1936, unemployed workers from Jarrow, a town in north-east England with 70% unemployment after its shipyards closed, organised a non-political “hunger march” to London which became known as the Jarrow crusade. More than 200 men, dressed in their Sunday best, marched peacefully in step for over 200 miles, gaining great support along the way. Yet when they reached London, prime minister Stanley Baldwin ignored their petition – and the men were informed their dole money would be docked because they had been unavailable for work over the past fortnight.

The Jarrow marchers en route to London in October 1936. National Media Museum/Wikimedia

The Jarrow marchers en route to London in October 1936. National Media Museum/WikimediaEurope was also facing a severe economic crisis. After Germany’s government refused to pay the reparations agreed in the 1919 Versailles treaty, saying they would bankrupt its economy, the French army occupied the German industrial heartland of the Ruhr and German workers went on strike, supported by their government. The ensuing struggle fuelled hyperinflation in Germany. By November 1923, it took 200,000 million marks to buy a loaf of bread, and the savings and pensions of the German middle class were wiped out. That month, Adolf Hitler made his first attempt to seize power in the failed “Beer hall putsch” in Munich.

In contrast, across the Atlantic, the US was enjoying a period of postwar prosperity, with a booming stock market and explosive growth of new industries such as car manufacturing. But despite emerging as the world’s strongest economic power, having financed much of the Allied war effort, it was unwilling to grasp the reins of global economic leadership.

The Republican US Congress, having blocked President Woodrow Wilson’s plan for a League of Nations, instead embraced isolationism and washed its hands of Europe’s problems. The US refused to cancel or even reduce the war debts owed it by the Allied nations, who eventually repudiated their debts. In retaliation, the US Congress banned all American banks from lending money to these so-called allies.

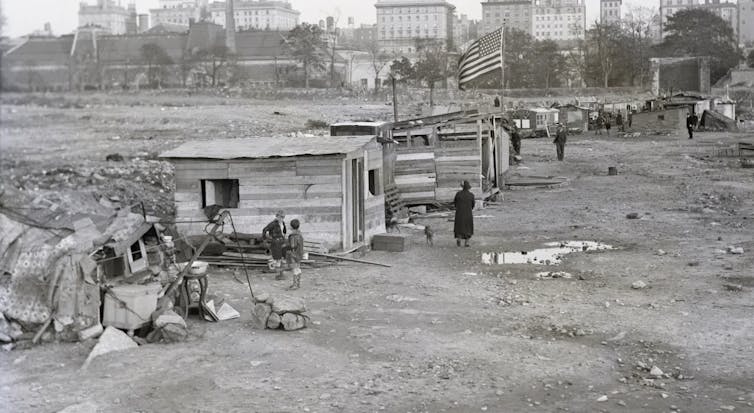

Then, in 1929, the affluent American “jazz age” came to an abrupt halt with a stock market crash that wiped off half its value. The country’s largest manufacturer, Ford, closed its doors for a year and laid off all its workers. With a quarter of the nation unemployed, long lines for soup kitchens were seen in every city, while those who had been evicted camped out wherever they could – including in New York’s Central Park, renamed “Hooverville” after the hapless US president of that time, Herbert Hoover.

Hooverville in New York’s Central Park during the Great Depression. Hmalcolm03/Wikimedia, CC BY-NC-ND

Hooverville in New York’s Central Park during the Great Depression. Hmalcolm03/Wikimedia, CC BY-NC-NDIn rural areas where the collapse in agricultural prices meant farmers could no longer make a living, armed farmers stopped food and milk trucks and destroyed their contents in a vain attempt to limit supply and raise prices. By March 1933, as President Franklin D. Roosevelt took office, the entire US banking system had ground to a standstill, with no one able to withdraw money from their bank account.

With its focus on this devastating Great Depression, the US refused to get involved in attempts at international economic cooperation. With no notice, Roosevelt withdrew from the 1933 London Conference which had been called to stabilise the world’s currencies – sending a message denouncing “the old fetishes of the so-called international bankers”.

With the US following the UK off the gold standard, the resulting currency wars exacerbated the crisis and further weakened European economies. As countries reverted to mercantilist policies of protectionism and trade wars, world trade shrank dramatically.

The situation became even worse in central Europe, where the collapse of the huge Credit-Anstalt bank in Austria in 1931 reverberated around the region. In Germany, as mass unemployment soared, centrist parties were squeezed and armed riots broke out between communist and fascist supporters. When the Nazis came to power, they introduced a policy of autarky, cutting economic ties with the west to build up their military machine.

The economic rivalries and antagonisms which weakened western economies paved the way for the rise of fascism in Germany. In some sense, Hitler – an admirer of the British empire – aspired to be the next hegemonic economic as well as military power, creating his own empire by conquering and ruthlessly exploiting the resources of the rest of Europe.

Troubled by rampant hyperinflation, Germans queue up with large bags to withdraw money from Berlin’s Reichsbank in 1923. Bundesarchiv/Wikimedia, CC BY-NC-SA

Troubled by rampant hyperinflation, Germans queue up with large bags to withdraw money from Berlin’s Reichsbank in 1923. Bundesarchiv/Wikimedia, CC BY-NC-SANearly a century later, there are some disturbing parallels with that interwar period. Like America after the first world war, Trump insists that countries the US has supported militarily now owe it money for this protection. He wants to encourage currency wars by devaluing the dollar, and raise protectionist barriers to protect domestic industry. The 1920s was also a time when the US sharply limited immigration on eugenic grounds, only allowing it from northern European countries which (the eugenicists argued) would not “pollute the white race”.

Clearly, Trump does not view the lack of international cooperation that could amplify the damaging economic effects of a stock or bond market crash as a problem that should concern him. And in today’s unstable world, for all the US’s past failings as a global leader, that is a very worrying proposition.

How the US responded to the last financial crisis

Once again, the rules of the international order are breaking down. While it is possible that Trump’s approach will not be fully adopted by his successor in the White House, the direction of travel in the US will almost certainly remain sceptical about the benefits of globalisation, with limited support for any worldwide economic rules or initiatives.

We see similar scepticism about the benefits of globalisation emerging in other countries, amid the rise of rightwing populist parties in much of Europe and South America – many backed by Trump. Fuelling these parties’ support are growing concerns about income inequality, slow growth and immigration which are not being addressed by the current political system – and all of which would be exacerbated by the onset of a new global economic crisis.

With the global economy and financial system far bigger than ever before, a new crisis could be even more severe than the one that occurred in 2008, when the failure of the banking system left the world teetering on the brink of collapse.

The scale of this crisis was unprecedented, but key US and UK government officials moved boldly and swiftly. As a BBC reporter in Washington, I attended the House of Representatives’ Financial Services Committee hearing three days after Lehman Brothers went bankrupt, paralysing the global financial system, to find out the administration’s response. I remember the stunned look on the face of the committee’s chairman, Barney Frank, when he asked US Treasury secretary Hank Paulson and US Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke how much money they might need to stabilise the situation:

“Let’s start with US$1 trillion,” Bernanke replied coolly. “But we have another US$2 trillion on our balance sheet if we need it.”

Documentary on the collapse of Lehman Brothers bank in September 2008.

Shortly afterwards, the US Congress approved a US$700 billion rescue package. While the global economy has still not fully recovered from this crisis, it could have been far worse – possibly as bad as the 1930s – without such intervention.

Around the world, governments ended up pledging US$11 trillion to guarantee the solvency of their banking systems, with the UK government putting up a sum equivalent to the country’s entire yearly GDP. But it was not just governments. At the G20 summit in London in April 2009, a new US$1.1 trillion fund was set up by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to advance money to countries that were getting into financial difficulty.

The G20 also agreed to impose tougher regulatory standards for banks and other financial institutions that would apply globally, to replace the weak regulation of banks that had been one of the main causes of the crisis. As a reporter at this summit, I recall widespread excitement and optimism that the world was finally working together to tackle its global problems, with the host prime minister, Gordon Brown, briefly glowing in the limelight as organiser of that summit.

Behind the scenes, the US Federal Reserve had also been working to contain the crisis by quietly passing on to the world’s other leading central banks nearly US$600 billion in “currency swaps” to ensure they had the dollars they needed to bail out their own banking systems. The Bank of England secretly lent UK banks £100 billion to ensure they didn’t collapse, although two of the four major banks, Royal Bank of Scotland (now NatWest) and Lloyds, ultimately had to be nationalised (to different extents) to keep the financial system stable.

However, these rescue packages for banks, while much needed to stabilise the global economy, did not extend to many of the victims of the crash – such as the 12 million US households whose homes were now worth less than the mortgage they had taken out to pay for them, or the 40% of households who experienced financial distress during the 18 months after the crash. And the ramifications of the crisis were even greater for those living in developing countries.

A few months after the 2008 financial crisis began, I travelled to Zambia, an African country totally dependent on copper exports for its foreign exchange. I visited the Luanshya copper mine near Ndola in the country’s copper belt. With demand for copper (used mainly in construction and car manufacturing) collapsing, all the copper mines had closed. Their workers, in one of the few well-paid jobs in Zambia, were forced to leave their comfortable company homes and return to sharing with their relatives in Lusaka without pay.

Zambia’s government was forced to shut down its planned poverty reduction plan, which was to be funded by mining profits. The collapse in exports also damaged the Zambian currency, which dropped sharply. This hit the country’s poorest people hard as it raised the price of food, most of which was imported.

The ripple effects of the 2008 global financial crisis soon hit Luanshya copper mine in Zambia. Nerin Engineering Co., CC BY-SA

The ripple effects of the 2008 global financial crisis soon hit Luanshya copper mine in Zambia. Nerin Engineering Co., CC BY-SAI also visited a flower farm near Lusaka, where Dutch expats Angelique and Watze Elsinga had been growing roses for export for over a decade – employing more than 200 workers who were given housing and education. As the market for Valentine’s Day roses collapsed, their bankers, Barclays South Africa, suddenly ordered them to immediately repay all their loans, forcing them to sell their farm and dismiss their workers. Ultimately, it took a US$3.9 billion loan from the IMF and World Bank to stabilise Zambia’s economy.

Should another global financial crisis hit, it is hard to see the Trump administration (and others that follow) being as sympathetic to the plight of developing countries, or allowing the Federal Reserve to lend major sums to foreign central banks – unless it is a country politically aligned with Trump, such as Argentina. Least likely of all is the idea of Trump working with other countries to develop a global trillion-dollar rescue package to help save the world economy.

Rather, there is a real worry that reckless actions by the Trump administration – and weak global regulation of financial markets – could trigger the next global financial crisis.

What happens if the US bond market collapses?

Economic historians agree that financial crises are endemic in the history of global capitalism, and they have been increasing in frequency since the “hyper-globalisation” of the 1970s. From Latin America’s debt crisis in the 1980s to the Asia currency crisis in the late 1990s and the US dotcom stock market collapse in the early 2000s, crises have regularly devastated economies and regions around the world.

Today, the greatest risk is the collapse of the US Treasury bond market, which underpins the global financial system and is involved in 70% of global financial transactions by banks and other financial institutions. Around the world, these institutions have long regarded the US bond market, worth over $30 trillion, as a safe haven, because these “debt securities” are backed by the US central bank, the Federal Reserve.

Increasingly, the unregulated “shadow banking system” – a sector now larger than regulated global banks – is deeply involved in the bond market. Non-bank financial institutions such as private equity, hedge funds, venture capital and pension funds are largely unregulated and, unlike banks, are not required to hold reserves.

Bond market jitters are already unnerving global financial markets, which fear its unravelling could precipitate a banking crisis on the scale of 2008 – with highly leveraged transactions by these non-bank financial institutions leaving them exposed.US bonds play a key role in maintaining the stability of the global economy. Video: Wall Street Journal.

Buyers of US bonds are also troubled by the Trump administration’s plan to raise the US deficit even higher to pay for tax cuts – with the national debt now forecast to rise to 134% of US GDP by 2035, up from 120% in 2025. Should this lead to a widespread refusal to buy more US bonds among jittery investors, their value would collapse and interest rates – both in the US and globally – would soar.

The governor of the Bank of England, Andrew Bailey, recently warned that the situation has “worrying echoes of the 2008 financial crisis”, while the head of the IMF, Kristalina Georgieva, said her worries about the collapse of private credit markets sometimes keep her awake at night.

A bad situation would grow even worse if problems in the bond market precipitate a sharp decline in the value of the dollar. The world’s “anchor currency” would no longer be seen as a safe store of value – leading to more withdrawals of funds from the US Treasury bond market, where many foreign governments hold their reserves.

A weaker dollar would also hit US exporters and multinational companies by making their goods more expensive. Yet extraordinarily, this is precisely the course advocated by Stephen Miran, chair of the US president’s Council of Economic Advisors – who Trump appears to want to be the next head of the Federal Reserve.

One example of what could happen if bond markets become destabilised occurred when the shortest-lived prime minister in UK history, Liz Truss, announced huge unfunded tax cuts in her 2022 budget, causing the value of UK gilts (the equivalent of US Treasury bonds) to plummet as interest rates spiked. Within days, the Bank of England was forced to put up an emergency £60 billion rescue fund to avoid major UK pension funds collapsing.

In the case of a US bond market crash, however, there are growing fears that the US government would be unable – and unwilling – to step in to mitigate such damage.

A new era of financial chaos

Just as worrying would be a crash of the US stock market – which, by historic standards, is currently vastly overvalued.

Huge recent increases in the US stock market’s overall value have been driven almost entirely by the “magnificent seven” hi-tech companies, which alone make up a third of its total value. If their big bet on artificial intelligence is not as lucrative as they claim, or is overshadowed by the success of China’s AI systems, a sharp downturn, similar to the dotcom crash of 2000-02, could well occur.

Jamie Dimon, head of the US’s biggest bank JPMorgan Chase, has said he is “far more worried than other [experts]” about a serious market correction, which he warned could come in the next six months to two years.

Big tech executives have been overoptimistic before. Reporting from Silicon Valley in 2001 as the dotcom bubble was bursting, I was struck by the unshakeable belief of internet startup CEOs that their share prices could only go up.

Furthermore, their companies’ high stock valuations had allowed them to take over their competitors, thus limiting competition – just as companies such as Google and Meta (Facebook) have since used their highly valued shares to purchase key assets and potential rivals including YouTube, WhatsApp, Instagram and DeepMind. History suggests this is always bad for the economy in the long run.

With the business and financial worlds now ever more closely linked, not only has the frequency of financial crises increased in the last half-century, each crisis has become more interconnected. The 2008 global financial crisis showed how dangerous this can be: a global banking crisis triggered stock market falls, collapses in the value of weak currencies, a debt crisis in developing countries – and ultimately, a global recession that has taken years to recover from.

The IMF’s latest financial stability report summarised the situation in worrying terms, highlighting “elevated” stability risks as a result of “stretched asset valuations, growing pressure in sovereign bond markets, and the increasing role of non-bank financial institutions. Despite its deep liquidity, the global foreign exchange market remains vulnerable to macrofinancial uncertainty.”The IMF has warned about instability in the global financial system. Video: CGTN America.

I believe we may be entering a new era of sustained financial chaos during which the seeds sown by the death of globalisation – and Trump’s response to it – finally shatter the world economic and political order established after the second world war.

Trump’s high and erratically applied tariffs – aimed most strongly at China – have already made it difficult to reconfigure global supply chains. Even more worrying could be the struggle over the control of key strategic raw materials like the rare earth minerals needed for hi-tech industries, with China banning their export and the US threatening 100% tariffs in return (as well as hoping to take over Greenland, with its as-yet-untapped supply of some of these minerals).

This conflict over rare earths, vital for the computer chips needed for AI, could also threaten the market value of high-flying tech stocks such as Nvidia, the first company to exceed US$4 trillion in value.

The battle for control of critical raw materials could escalate. There is a danger that in some cases, trade wars might become real wars – just as they did in the former era of mercantilism. Many recent and current regional conflicts, from the first Iraq war aimed at the conquest of the oilfields of Kuwait, to the civil war in Sudan over control of the country’s goldmines, are rooted in economic conflicts.

The history of globalisation over the past four centuries suggests that the presence of a global superpower – for all its negative sides – has brought a degree of economic stability in an uncertain world.

In contrast, a key lesson of history is that a return to policies of mercantilism – with countries struggling to seize key natural resources for themselves and deny them to their rivals – is most likely a recipe for perpetual conflict. But this time around, in a world full of 10,000 nuclear weapons, miscalculations could be fatal if trust and certainty are undermined.

The challenges ahead are immense – and the weakness of international institutions, the limited visions of most governments and the alienation of many of their citizens are not optimistic signs.

This is the second in a two-part series. In case you missed it, read part one here.

For you: more from our Insights series:

Could digital currencies end banking as we know it? The future of money

Welcome to post-growth Europe – can anyone accept this new political reality?

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.![]()

Steve Schifferes, Honorary Research Fellow, City Political Economy Research Centre, City St George's, University of London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Unsplash,

Unsplash,