David Clode/Unsplash, CC BY

Kate Dooley, The University of Melbourne

David Clode/Unsplash, CC BY

Kate Dooley, The University of MelbourneAhead of the United Nations climate summit in Belém last month, Brazil’s President Lula da Silva urged world leaders to agree to roadmaps away from fossil fuels and deforestation and pledge the resources to meet these goals.

After failing to secure consensus, COP president Andre Corrêa do Lago announced these roadmaps as a voluntary initiative. Brazil will report back on progress at next year’s UN climate summit, COP31, when it hands the presidency to Turkey and Australia chairs the negotiations.

These goals originate in the outcomes of the first global stocktake of the world’s progress towards the Paris Agreement goals, undertaken in 2023.

At the COP28 talks in Dubai in that year, there was an agreement to transition away from fossil fuels and to halt and reverse deforestation and forest degradation by 2030.

Yet achieving these goals relies on a “just transition”, where no country is left behind in the transition to a low-carbon future, including a “core package” of public finance to address climate adaptation, and loss and damage. The Belém outcome fell short.

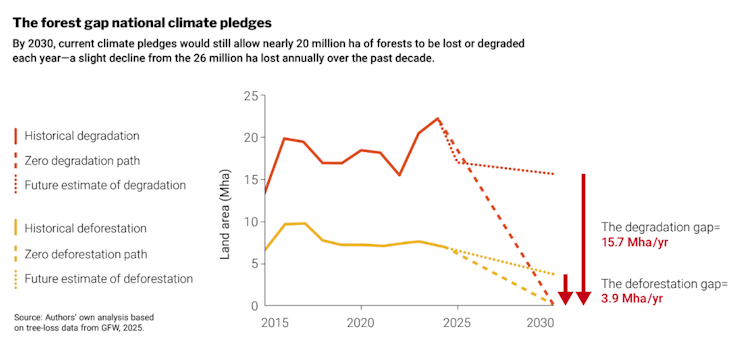

Forest loss and degradation is continuing, at an average rate of 25 million hectares a year over the last decade, according to the Global Forest Watch. This is 63% higher than the rate needed to meet existing targets to halt and reverse forest loss by 2030. Yet the climate pledges submitted for the Belém COP remain far off track from this goal.

In the 2025 Land Gap Report, my colleagues and I calculated the scale of this “forest gap” – the gap between 2030 targets and the plans countries are putting forward in their climate pledges.

We show the pledges submitted up until this year’s climate summit would cut deforestation by less than 50% by 2030, meaning forests spanning almost 4 million hectares would still be cut down. The pledges would lead to forest degradation – where the ecological integrity of a forest area is diminished – of almost 16 million hectares. This is only a 10% reduction on current rates.

Together, this equates to an anticipated “forest gap” of around 20 million hectares expected to be lost or degraded each year by 2030. That’s about twice the size of South Korea.

While this underscores the inadequacy of commitments, the analysis is based on pledges submitted up to the start of November 2025, at which point only 40% of countries had submitted an updated plan. Major pledges submitted during COP31, such as from the European Union and China, don’t change this analysis.

This graph shows that deforestation will only slightly decline to 2030. The Land Gap Report, author supplied., CC BY-ND

This graph shows that deforestation will only slightly decline to 2030. The Land Gap Report, author supplied., CC BY-NDA new fund for forest conservation called the Tropical Forests Forever Facility was launched in Brazil, attracting $US6.7 billion in pledges ($A9.9 billion).

The forest fund focuses on tropical deforestation, the leading cause of emissions from forest loss. But it has a key weakness: the limited monitoring of forest degradation, which could allow countries to receive payments while still logging primary forests.

The fund will establish a science committee and plans to revise monitoring indicators over the next three years, creating an opportunity to strengthen its ability to protect tropical forests.

The COP30 leaders’ summit also saw the launch of a historic pledge of $US1.8 billion ($A2.7 billion) to support conservation and recognition of 160 million hectares of Indigenous Peoples’ and local communities’ territories in tropical forest countries.

But global action on forests needs to extend beyond the tropics. Across both deforestation and forest degradation, countries in the global north are responsible for over half of global tree cover loss over the past decade.

A global accountability framework on forests is needed to increase ambition on climate action, including in countries and regions with extensive forests outside of the tropics, such as Australia, Canada and Europe.

In these regions, industrial logging is a major driver of tree-cover loss but receives far less political attention than tropical deforestation. Wide gaps in reporting – between deforestation and degradation – mean logging-related degradation often goes unreported.

In a recent report, only 59 countries said they monitor forest degradation. Of these, almost three-quarters are tropical forest countries.

The IUCN World Conservation Congress which convened in Abu Dhabi this year prior to the climate talks, passed a motion on delivering equitable accountability and means of implementation for international forest protection goals. This arose from a recognised need to promote greater equity between forest protection standards across countries.

All of this points to an urgent need to tackle accountability in global forest governance. The forest roadmap to be developed for COP31 in Turkey could help drive stronger alignment and transparency across UN processes – from the UN Forum on Forests’ 2017–2030 plan to the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework’s 2030 target to halt and reverse biodiversity loss.

Australia could help shape global forest ambition in the year ahead. It is currently the only country whose emissions pledge promises to halt and reverse deforestation and degradation by 2030 – a clear signal that developed countries must lead.

As President of Negotiations at COP31, Australia can also work to bring Brazil’s fossil-fuel and forest roadmaps into formal negotiations. But this depends on two things: credible leadership from developed countries and long-overdue climate finance. As a deforestation hotspot with ongoing native forest logging, Australia has considerable work to do to meet this responsibility.![]()

Kate Dooley, Senior Research Fellow, School of Geography, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

.jpg)

Ross and Hugo Turner attempting to break a record, flying a paraglider-style aircraft at 10,000ft in the French Alps – via SWNS

Ross and Hugo Turner attempting to break a record, flying a paraglider-style aircraft at 10,000ft in the French Alps – via SWNS Ross and Hugo, the Turner Twins, on a para-motor flying over French Alps breaking altitude record – via SWNS

Ross and Hugo, the Turner Twins, on a para-motor flying over French Alps breaking altitude record – via SWNS The Turner Twins making final preparations for a world altitude record in a tandem electric paramotor – SWNS

The Turner Twins making final preparations for a world altitude record in a tandem electric paramotor – SWNS

.jpg)

.png)